In February and March 2021, Fatah and Hamas, the two rival Palestinian political parties, reached an agreement to hold elections for the presidency of the Palestinian Authority, its Legislative Council, and Hamas’ entry into the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). The elections were planned to take place in accordance with the Oslo Accords, after which negotiations would continue with Israel toward the establishment of a Palestinian state.

The agreement included a commitment to uphold international law, establish a state within the 1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital, recognize the PLO as the legitimate and exclusive umbrella framework, conduct a peaceful popular struggle, and transfer the separate government in the Gaza Strip to the Palestinian Authority.

President Mahmoud Abbas sent the agreement to the new Biden administration and European governments in the hope that they would support holding national elections with Hamas’ participation, and would then pressure Israel to allow voting across the occupied territories, including in East Jerusalem. In Abbas’ eyes at the time, Hamas’ signing of the deal was a winning card; apparently, it included a concession by Hamas not to put forward a presidential candidate on its behalf, thus leaving it to Abbas to run again virtually unchallenged.

The Fatah-Hamas agreement did not come out of the blue. Four years earlier, Hamas published its “General Principles and Policies,” a revised organizational document that significantly deviated from the fundamentalist principles of the group’s original charter from 1987, and that effectively accepted the Oslo Accords as an existing political fact. Even earlier, in 2014, in the presence and mediations of the Emir of Qatar in Doha, the Fatah leadership headed by Abbas met with the Hamas leadership headed by Khaled Mash’al. The full minutes of the talks were published in an official Emirati document. In essence, the message of the Hamas leadership was clear: “If you in Fatah are convinced that you can get a state from Israel along the 1967 lines through negotiations, go for it. We will not interfere.”

As expected, Israel objected to including East Jerusalem in the elections, seeing it as undermining its claims to sovereignty over the occupied and annexed part of the city. Still, Hamas offered to hold the elections anyway, and accepted the restriction imposed by Israel. But Israel and the United States exerted heavy pressure on Abbas to cancel them all the same.

There were certainly political reasons for Abbas to call off the elections and for Hamas to push for them. Public opinion polls showed that the vast majority of Palestinians wanted Abbas to end his tenure, and that Hamas could stand to win another electoral victory. However, those polls also indicated that Marwan Barghouti, the prominent political prisoner who intended to run from his Israeli jail cell, would win over any other presidential candidate. Had elections not been canceled, and a popular leader emerged democratically, we would likely be in a very different political reality.

In the end, Abbas capitulated under severe pressure. The “Unity Intifada” began a few days later, and with it, Hamas’ Operation “Sword of Jerusalem” and Israel’s “Operation Guardian of the Walls.” According to reports in the New York Times and Washington Post, it was around that same time that Al-Aqsa Brigades, Hamas’ military wing, began conceiving and planning what would become “Al-Aqsa Flood” — the murderous assault of October 7.

‘Never been better’

As many have raised, there are quite a few parallels between last month’s assault and the surprise attack on Israel that happened five decades earlier, in the Yom Kippur War. Operationally, in both 1973 and 2023, Israel’s intelligence chiefs did not pay enough attention to their enemies’ military movements on the ground. Strategically, a neighboring Arab state had sent Israel an alert that was not taken seriously: in 1973, it was Jordan’s King Hussein, and in 2023, Egyptian intelligence. Yet in both cases, the Israeli establishment arrogantly relied on a misconception that its military victories had successfully deterred its enemies.

After each assault, however, everything changed. Despite losing militarily, the achievements of Egypt and Syria in the 1973 war “restored Arab honor,” according to the Egyptian narrative, reclaiming some of what had been lost in Israel’s victory in the 1967 war. Similarly, last month’s Hamas offensive hit Israel at a scale and intensity that no other Palestinian organization has ever done. And Israel will not be able to erase this fact.

As in 1973, the fundamental failure of October 7 was political. In 1971, two years before the war, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat proposed a partial arrangement with Israel, in which the latter would withdraw some 30 kilometers from the Suez Canal to the Mitla Strait and the strategic ridge of Um Hashiba. The Suez would be opened for international navigation, and Egyptian cities on the western side of the Canal that were destroyed by Israeli shelling during the “war of attrition” after 1967 would be rehabilitated. A small number of Egyptian troops would also move to the area from which Israel would withdraw to symbolize the return of Egyptian sovereignty. This arrangement, in turn, would serve as a link toward a more comprehensive agreement based on UN Security Council Resolution 242.

With this proposal — which roughly corresponded to Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan’s ideas at the time — Sadat tried to break the diplomatic deadlock in the region. But Prime Minister Golda Meir did not trust Sadat and his stated goal of peace, even though U.S. Secretary of State William Rogers was convinced of his sincerity. In Meir’s view, there was no difference between Sadat and his predecessor, the pan-Arab nationalist Gamal Abdel Nasser, and both in her eyes simply wanted to destroy Israel. Meir remained stubborn, Dayan relented, and Rogers returned to Washington empty-handed.

After the terrible war, in which over 2,600 Israelis were killed and 300 soldiers were captured, Israel signed an armistice agreement with Egypt in 1974, the terms of which bore remarkable resemblance to Sadat’s 1971 proposal.

When Meir first rejected Sadat’s overtures in 1971, she, like much of the Israeli establishment after the Six-Day War, believed that the country’s position “has never been better.” Indeed, this was actually the slogan of the ruling Alignment party (an incarnation of the founding Labor party) ahead of elections which were supposed to take place in late 1973.

The same arrogance was evident in 2021, when Israel opposed Palestinian elections and pressured Abbas to drop his dealings with Hamas. Netanyahu, like Meir, believed that the government’s policies were successful, and that allowing elections and reorganizing of the Palestinian political leadership would destroy everything Israel had built. Success blinded Israel, and as in 1973, it thought it had never been better.

Returning to the 2021 outline

Since 2006, Israel’s policy toward the Palestinians has consisted of three key components, all supported by the United States and European countries. First, Israel will have total control over the Gaza Strip from the outside, ensuring the physical, legal, and political separation of Gaza from the West Bank, and the maintenance of the rivalry between Fatah and Hamas. In this context, Israel tried to tame Hamas by allowing foreign funding to help it hold the reins of power, along with periodic military strikes to curb its power and force it to abide by the Israeli order.

Second, Israel preferred to manage the conflict with the Palestinians as a whole rather than resolving it. In fact, along with the expansion of West Bank settlements, Israel created a single regime with its supremacy between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, and turned the PA into a subcontractor that controls the Palestinians on its behalf.

Third, Israel has worked to significantly reduce the wider Israeli-Arab conflict through normalization agreements with Arab states and to leave the Palestinians isolated and weak. The signing of the Abraham Accords was in effect a declaration of the abandonment of the Palestinians to Israel’s mercy.

Just when Israel’s policy was about to reach the peak of its success, through a normalization agreement with Saudi Arabia and the completion of a sophisticated wall around the Gaza Strip, everything collapsed on October 7, at terrible human cost to Israelis and Palestinians. And it could have been different.

It was not only Netanyahu who shaped Israeli policy. Since 2006, Israel’s political and security establishments — all their politicians, generals, and intelligence chiefs — have been full partners in formulating and implementing the now-collapsed approach. Many of them still do not grasp the extent to which Hamas’s bloody offensive requires a drastic change of direction. Rather, they seek to return to the previous principles and find a subcontractor to manage the Gaza Strip on Israel’s behalf, whether it be some local entity, Abbas’ PA or an international body. But no such entity can function without legitimacy granted to it by Palestinian elections; otherwise, it would simply be perceived as an illegitimate collaborator with the cruel occupier.

In other words, we must return to the political outline that was rejected in 2021 in order to create a new reality. Elections are not only about producing results, but about providing a process for parties to renew themselves and their politics. Beyond a ceasefire, we need Palestinian elections as a game changer that can lead to an independent Palestine over all of 1967-occupied territories, instead of replicating the failed order that Israel imposes in the West Bank onto the Gaza Strip.

Most read on +972

This is the framework that must be set against the Israeli far right, which sees an opportunity in this moment. The far right does not want to return to the preceding arrangements, but rather establish a new, cruel order as consequential as the Nakba of 1948, starting with the Gaza Strip: exile as many Palestinians from Gaza as possible; build settlement cities including the re-building of those evacuated in 2005; then, implement the same plan in the West Bank with the same ferocity.

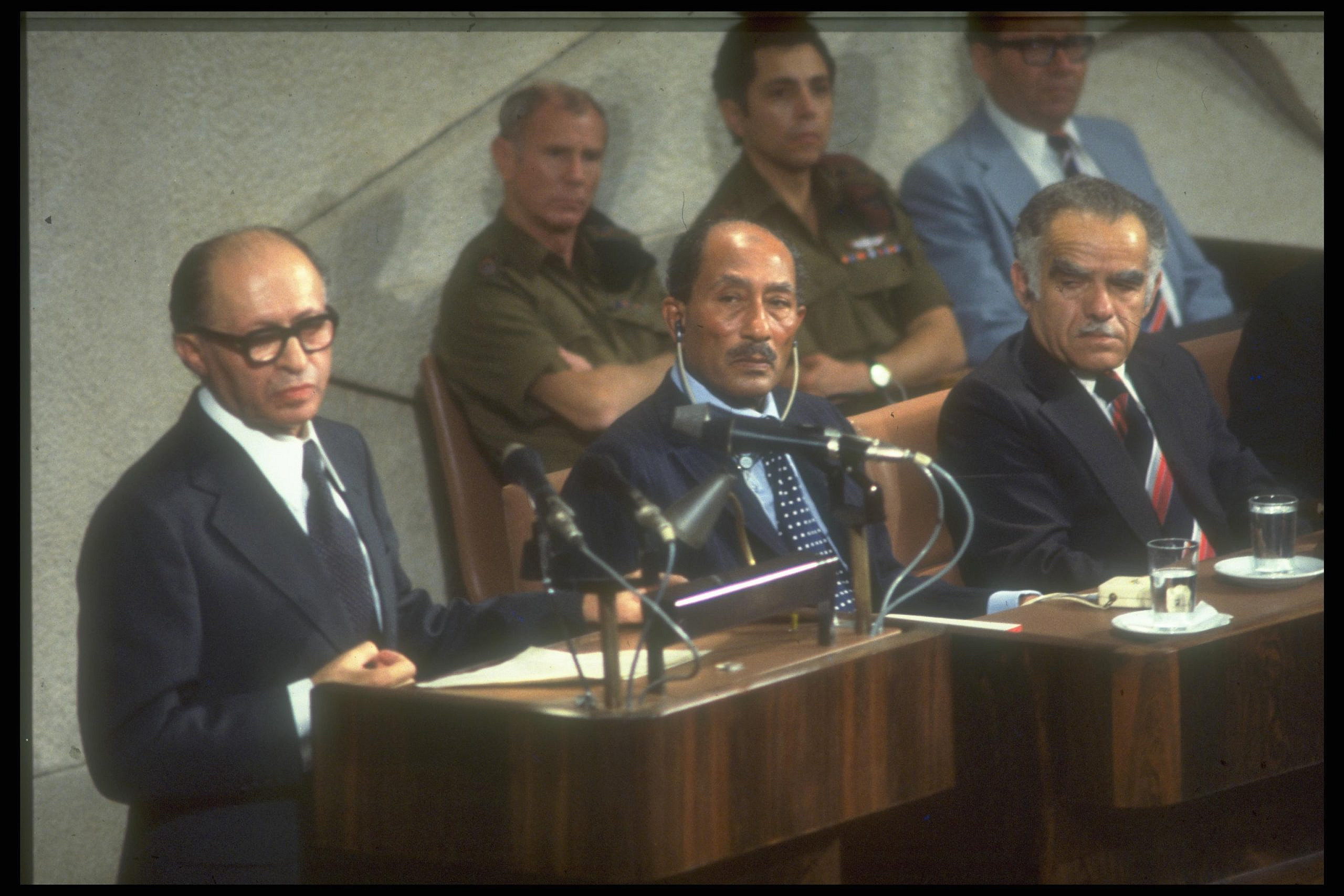

History has precedents for deterring this terrible path. In 1973-4, it was Henry Kissinger, the U.S. Secretary of State, who pushed Israel to refrain from decimating an Egyptian military unit, thwarting an Israeli attempt to renew the fighting with Egypt once the ceasefire was implemented; it was he, too, who oversaw the signing of two interim agreements between Israel and Egypt. These paved the way for Sadat’s trip to Jerusalem in 1977, and a peace settlement brokered by President Jimmy Carter in 1978-9.

Is there now an American entity of similar weight and willpower to do the same between Israel and the Palestinians?

A version of this article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.