Since January, the world of Israeli politics has been consumed by the frenzy surrounding the government’s proposed “judicial reform.” The coalition’s attempt to gut the judiciary — which, critics argue, would pave the way for the realization of the Israeli right’s greatest wishes, such as annexation of the West Bank — was supposed to be passed quickly and easily. It has, however, faced an unexpectedly forceful opposition, with tens of thousands of Israelis pouring into the streets in mass demonstrations every week for several months. The strength and frequency of the protests forced Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s hand, and a few weeks ago he announced a brief “pause” on the legislation.

While neither side has backed down since that announcement, the pause presents an opportunity to examine the purported “reform” and the opposition to it through a wider lens. Indeed, though the legislation and the opposition to it seemed to emerge ex nihilo, both have deep historical roots that bear study — and should give us cause for concern.

To help illuminate this history and where both sides seem to be headed, +972 spoke with Dr. Dahlia Scheindlin, a scholar and leading public opinion analyst (and a founding member of and longtime contributor to the site) who has studied the Israeli judiciary extensively and whose book on the topic is slated for release in late 2023.

In this interview, Scheindlin offers insight into the evolution of the judiciary’s role in the politics of both the Israeli right and left, and why various factions of Israeli society have historically been opposed to it as a check on government power. Taken together, these threads should worry those who think the current opposition represents a decisive step toward equality and justice: rather, Scheindlin notes, the commitment to these ideas are more fragile than many would hope.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How long has the Israeli right wanted to reform the court and the judicial system more generally? Most people seem to see the emergence of the current battle over the judicial system as pretty sudden. Is it something totally new?

Well, with a short view of history, I would say the right began talking about various pieces of the judicial reform in the early 2010s. But it’s important to start out with the long view: the right wing in Israel has wanted some kind of judicial reform since the beginning of statehood, back when the right was a big advocate of a constitution, and more independent courts, and the supremacy of law, and human and individual rights.

Sorry — you said the right was in favor of a constitution?

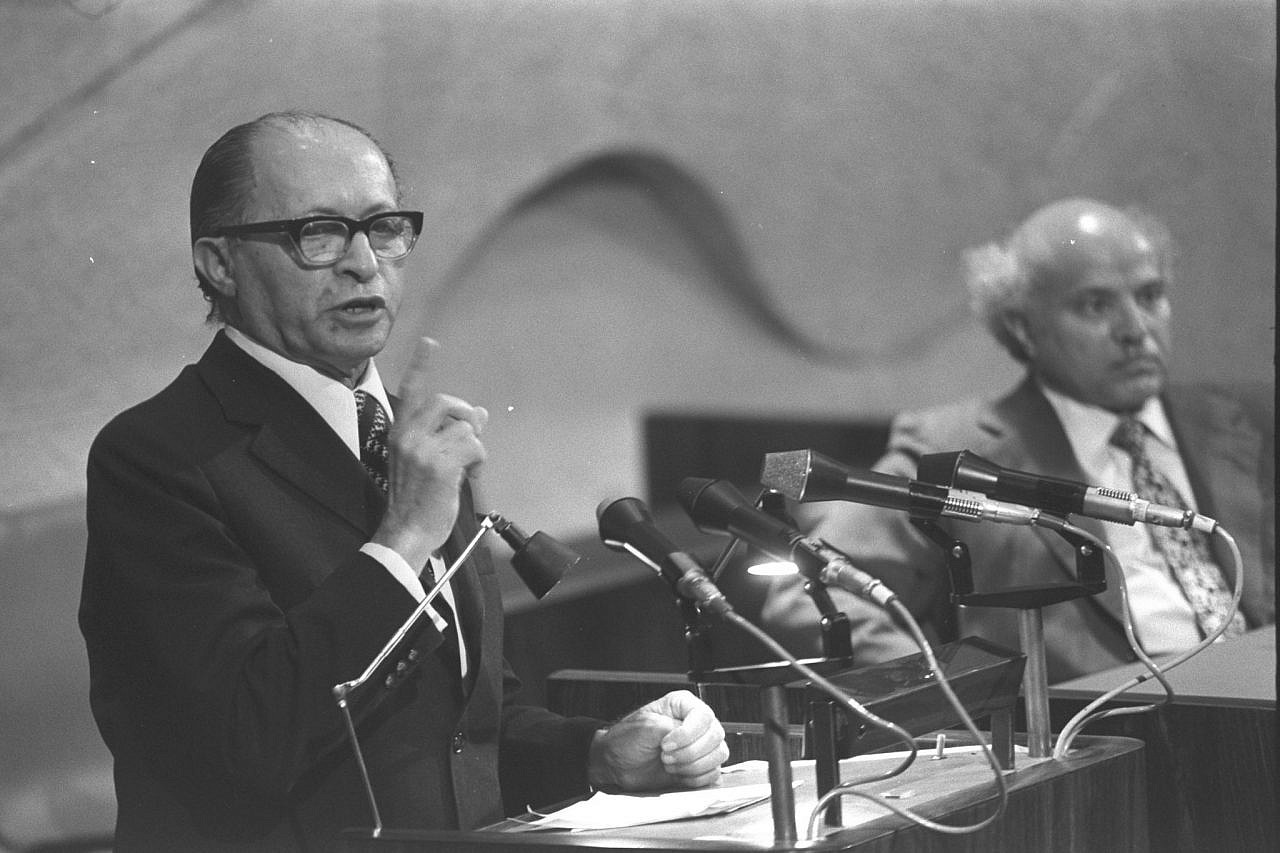

Yes! Menachem Begin was a forceful advocate for a constitution even before the Harari decision [a 1950 Knesset act proposing the system of quasi-constitutional Basic Laws in lieu of a formal constitution]. Likud was in power, and there was a fully right-wing government, when the Basic Laws [Human Dignity and Liberty, and Freedom of Occupation] were passed in the early 1990s. Likud figures spearheaded those laws, together with opposition parties, specifically Shinui [a centrist party]. And it was with the one vote from the National Religious Party that the Basic Laws of 1992 were able to pass. This was a change that the right wing wanted, and there was a particular confluence of circumstances that made both the right and the left want those Basic Laws.

This is obviously not the reform you asked about and that we’re focused on today, where the right wants to constrain, if not stamp out, the independence of the judiciary. But the right wing historically supported the independence of the judiciary, and was an advocate for the judiciary to balance out the power of the elected branch. You could say this was cynical because they weren’t in power for much of the early history of the state, so of course they wanted protection for the opposition, for the individual. But they were also really ideologically committed, as lower-case “l” liberals, to individual rights and liberal protection of those rights. Remember, the right wing in Israel, from the early years, made common cause with the liberal parties, in contrast with the socialist-leaning parties.

So when we talk about the particular form of judicial reform that’s being passed now, we have to remember that it’s a reversal of what the Israeli right stood for historically, and not in the very distant past either. You don’t have to go back to 1948 to find this commitment to the judiciary manifest. In fact, in the Likud party platform from 1973 and 1977, they published a very elaborate and beautiful draft constitution that included guarantees of equality, civil rights, human rights — all the normal things you would see in a constitution.

I didn’t even know this until recently, but in 1993, after the passage of the Basic Laws, the Likud Central Committee published a document taking pride in how they had helped to advance what they called a mahapecha shiputit [judicial revolution], which is so ironic because they always blame [former Chief Justice of the Israeli Supreme Court] Aharon Barak for inventing the “judicial revolution” in 1995. They’re just such hypocrites. Their own internal documents say stuff like, “We’re so happy that we passed these Basic Laws,” and “We’re so proud that we have finally determined the supremacy of law in Israel including limitations on the legislature.” It’s in that document. It’s amazing.

If Likud and other right-wing parties were previously in favor of liberal ideals like equality and civil rights, what drove them down the path of illiberalism they’re currently on?

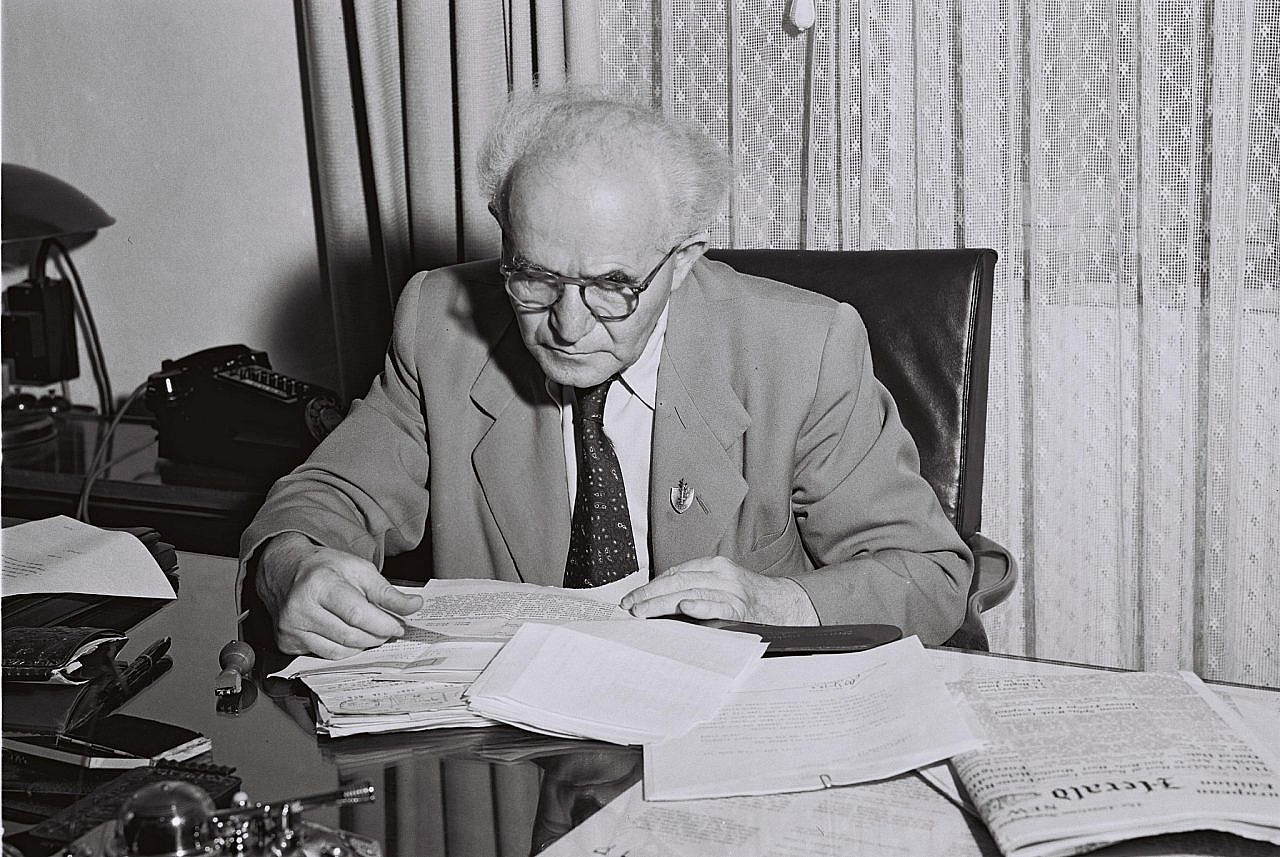

For one thing, anybody in power long enough tries to entrench their power. So it was not an accident that David Ben-Gurion was against the constitution in the beginning of statehood, because he didn’t want his power limited, among other reasons. And it’s not an accident that when the right wing is very entrenched in power, they get a little drunk on power and they want to resist any limitations on it.

But how did the right in particular move towards illiberalism? I think that it’s a combination, first of the historical alliance with the religious parties, which, let’s face it, was a historical alliance the left has made as well. Mapai [the Labor party of Ben-Gurion that dominated Israeli politics for the first three decades of the state] set the tone for governance in Israel by insisting on the Haredim [ultra-Orthodox Jews] being in the first coalition, at the expense of Arab parties. In other words, they never wanted to depend on anything other than Jewish parties, so they needed the Haredim to be in the coalition.

Right away, they were subject to coalition bartering for Haredi demands. And when the Haredim didn’t get their demands, they bolted from the government. This happened at the very beginning of statehood, so it’s important to say that the left was in this position too. But the fact is that the right, having won power, had to revive the partnership with the ultra-Orthodox. You need to always have exceptions to basic constitutional principles when you have Haredim in your coalition — specifically the principle of equality, and particularly equality with relation to military service.

The other factor is the rise of Netanyahu and illiberal populism around the world. Netanyahu always had a populist streak in terms of style. He was always attacking the media, always riling up the crowds, always getting people to chant, always on an ego trip. By 2009, when he came back into power [for the first time since 1999], there’s a whole global wave of illiberal nationalist populists. We forget that there was already a first generation of these politicians in the mid-2000s, in the years before Netanyahu got back into power; they were all running on anti-immigrant platforms and xenophobia.

Someone who definitely sounded a lot like them at the time was Avigdor Lieberman [of the Yisrael Beiteinu party]. In 2009, Lieberman won 15 seats — more than ever before or since. And guess where those seats came from? They came at the expense of Likud. This is my theory, and it’s not like anybody can prove it, but I think this is what got Netanyahu into the [illiberal] game, conscious of Lieberman’s influence or not. Netanyahu took skills he already had, followed a global trend, and he smashed his most threatening competitor. All of a sudden, he and his party dive headlong into the populist illiberal nationalist agenda.

The coalition Netanyahu formed with Lieberman put forward all this illiberal legislation designed to intimidate citizens, especially Palestinians: anti-BDS laws, the Nakba Law, the extension of the family separation law. Then, of course, they begin drafting and debating the NGO laws designed to intimidate left-wing society and groups. And we see the first drafts of the [Jewish] Nation-State Law during that same Knesset term.

There was a flurry of activity taking these pieces of legislation to court, and the Supreme Court mostly upheld the laws. But this infuriated the right nonetheless, because they didn’t like the fact that the Court even ruled on these things, and that on very rare occasions the Court ruled against them. The right started using rhetoric to delegitimize the activity of the Supreme Court, and tried to pass bills to limit the Court’s jurisdiction. But there was no real momentum for it, it wasn’t coming along with a bigger political program.

In 2012, right smack in the middle of the 18th Knesset, the Kohelet Policy Forum was founded. Since then, Kohelet has been behind the Nation-State Law and a lot of the judicial reform. As a result, the organization has been getting a lot of heat recently. How influential is Kohelet? And are these laws drafted by Kohelet reflecting American or more homegrown ideology?

As far as I understand, Kohelet very much modeled itself on the Federalist Society in the United States. In that way, it’s like the worst of European and American populist, right-wing, nationalist illiberal trends converged in Israel starting in the early 2010s. Many Likud and right-wing politicians have formed connections with Kohelet and Moshe Koppel [the founder of Kohelet]: Miki Eitan, Zvika Hauser, Ayelet Shaked.

Now, remember, Kohelet is secretive. It’s just amazing how they’re shamelessly hypocritical, talking about things like wanting to advance democracy and restore the balance between the branches of government, and individual rights and liberalism. I don’t know if they actually use the word “transparency,” but they certainly try to portray themselves as the heroes of democracy while shamelessly hiding their sources of income. And they’re a little bit reticent about all that they actually do. So you can find their policy papers, but they’re cautious about laying out their full plans and attitudes with regard to the judiciary. Their website is strategically opaque.

Kohelet represents the ideological mishmash of the right: it’s not a clean copy-and-paste of conservative American policies, but they do draw on some tactics and language from the U.S., like an emphasis on freedom and libertarianism. And they do so to advance an Israeli ultranationalist, annexationist agenda that favors unfettered executive control.

You said earlier that figures like Ben-Gurion, who is usually affiliated with liberal Zionism, were not in favor of strong liberal institutions and ideas like equality and a constitution. How did the Israeli left come to be this lower-case-“l” liberal defender of democracy, and how new is that? Is it too cynical to say the center and center-left support for the Court is simply grounded in opposition to the right?

Civil rights were a liberal concept in the 1970s, not necessarily a left-wing one. The idea of defending individual rights, of the value of the individual over the collective — these went against the Mapai and Mapam parties, which were theoretically committed to socialism.

The easiest way to answer your question would be to say that in the earlier years of statehood, left and right were used to define who leaned toward socialist principles, whether in practice or in an idealized vision, and who leaned toward liberal rights and the value of individual freedoms. The philosophical question dividing right from left was a debate over collectivism versus individualism.

The other major difference, of course, was nationalism. The right wing in Israel longed for Greater Israel, while the left wing made the compromise on paper to accept the partition plan — not that it was ever very happy about it. Ben-Gurion never really liked giving up on the full Land of Israel, but they made that decision. It wasn’t as relevant [at the time] because Israel simply didn’t control the other territories.

The real change happened in the late 1970s and early ’80s. It took 10 years of the occupation, and for the left to be out of power, for reality to sink in. The left started to oppose occupation policy because they thought it was wrong for Israel and not nice to Palestinians, and in order to articulate why it was not nice to Palestinians, it seems to have sunk in that the occupation was a violation of civil and human rights. It’s not hard to jump from thinking that to thinking that civil and human rights matter inside Israel as well.

Then, something else happened: Israel’s economy changed. Israel went through total economic chaos, with runaway inflation and a bank crisis. The economic stabilization plan of 1985 pushed Israel toward a more privatized economy that is more global in its reach. That meant privatization and asserting free-market principles. Between 1985 and the early 1990s, the entire Israeli economic outlook shifted, and it went along with a value shift toward individual rights and freedoms — in other words, a shift toward liberalism.

Pivoting back to the right — why 2023? Another cynical take is that the reform is being put forward now because of Netanyahu’s corruption trial. Is it as simple as that, or is there a deeper reason for why this is blowing up now?

I don’t know if the date has much significance. What is important is the confluence of long-term interests and immediate interests. I wrote a piece for the New Republic in the summer of 2021 in which I said that if Netanyahu had won the fourth election [after three consecutive stalemate elections], all the forces would have been in place for a complete explosion of the judiciary. It was just delayed by a year, because he didn’t win the fourth round and did win the fifth.

But it precedes Netanyahu’s indictment. In the decade or so leading up to it, there was this absolute screaming cacophony of hostile rage against the Supreme Court. It was coming from all sides if you read the right-wing press, from Yisrael Hayom to [Arutz Sheva] to Makor Rishon — never mind, of course, online right-wing discourse. It started to be so intense that I thought we were headed for disaster with the courts, and when Netanyahu was indicted in early 2020, and on trial by 2021, it was only a matter of time.

Then you look at these longer-term trends. The Haredim have always resented judicial activism, or anything that the judiciary ever did to rule in favor of separation of religion and state, even in these tiny incremental ways that barely managed to move things forward. Haredim always feared that the Court would read equality into Israeli law, and that that would eventually lead to the Court taking away the Haredi exemption from the military draft.

And then you had the settler community, which has hated the Court for a long time, even though the Court basically gave backing to 90 percent of settlements. But they don’t see it that way — settlers only see the few rulings where the Court dared to rule against a settlement. They generally had the sense that the Court was too supportive of human rights for all people rather than privileging settlement projects, anything that went against what they considered unfettered control and expansion.

Religious people are not entirely to blame; the security forces have, over the course of Israeli history, operated outside the bounds of the law and resent being constrained by law, whether it’s by the Supreme Court or legal advisors. They’re also in the mix.

Speaking of longer-term historical trends: in an article you recently published on +972, you write about the string of failed attempts to draft a constitution. Israeli political factions of all kinds were opposed to a constitution, chiefly because they were opposed to enshrining the value of equality in Israeli law. Unlike those past attempts, which seem to have been led by politicians, calls for equality and a constitution today seem to be popularly driven. Does that change how you assess the current protest movement?

It’s not as unprecedented as it might seem. In the article, I was focused on the political attempts to draft a constitution. But it’s worth noting that in the 1980s, there was a sense that these coalition governments were sleazy and always subject to internal bargaining. There was a lot of public discontent. At that time, there was a movement called Huka l’Yisrael, or “Constitution for Israel,” and they mounted mass demonstrations in the streets. Like you’re seeing now, the movement back then wasn’t led by leftists; it was led largely by centrist, bourgeois, middle-class, educated elites.

From the Palestinian side, there were the Arab Vision documents from the 2000s, which were drafted by leaders and civil society groups among Palestinian citizens of Israel. They began a whole series of long-term dialogues in the early-to-mid 2000s that led to a series of documents called the “Future Vision of the Palestinian Arabs in Israel.” The Arab leadership felt like all those [constitutional] efforts were basically run by Jewish Zionist thinkers, and they weren’t really taking into account the actual considerations of Palestinians in Israel, so they started their own efforts. By the way, I think these Palestinian efforts became a touchstone for the right: it’s part of what drove Lieberman’s antipathy, the sense that Palestinians were articulating what Jews consider to be pretty hardline principles, and that Jews felt threatened by them.

It was very tempting for me, for many years, to think that the original sin was not having a constitution and that we could solve everything if we just had one. But a constitution does not solve everything — just look at the U.S. People have had the idea of drafting a constitution throughout Israeli history, but there’s a reason why it never passes. We have to remember that until we solve those fundamental contradictions, we’re never going to pass a constitution, or we’re going to pass a constitution that is full of compromises.

I don’t mean to be dreary. It doesn’t have to be dreary if we would just all agree that equality is a fundamental value. That would be a great start.