During these days of the coronavirus pandemic, the vast majority of the residents of this land are worried about their health and their economic and psychological state. Those worries are just as relevant for the residents of Shuafat Refugee Camp, situated within the municipal bounds of Jerusalem, yet located on the other side of the separation wall.

Adnan, a young hi-tech worker, says his body is slowly fraying after weeks without hugging anyone. Aysar, a chef at a local restaurant, can hardly sleep since his business shut down. Ilham, the daughter of a family of refugees from Jaffa, is worried about her aging mother who spends her days at home in her apartment.

But the residents of the camp suffer from an additional, especially cruel and unique problem: Israel has completely abandoned them behind the wall.

“The separation wall has disconnected us from Jerusalem and disconnected Jerusalem from us,” says Kamel Ja’abri, who helps run a youth organization in the camp and volunteers with Kulna Jerusalem, a local NGO that connects Israeli Jews and Palestinians in the city. “Right now, under the shadow of the coronavirus, that disconnect is dangerous.”

The central problem, says Ja’abri, is that the authorities have neither built a testing station in the camp nor established an isolation zone for people who have been infected. This kind of infrastructure is critical due to the immense population density of Shuafat, which makes effective social distancing difficult, particularly when considering the possibility that Israel may put the camp under lockdown — by shutting down the checkpoint at the entrance to Shuafat — in the case of an outbreak.

“If we see an outbreak [in Shuafat], the authorities won’t treat us like they did Bnei Brak, they will immediately close the checkpoint,” Ja’abri says. “It will be a disaster. The government had already considered doing this two weeks ago, despite there not being even one infection here. What will happen when we do have cases? They won’t care. No one will be taken to isolation centers.”

The separation wall was built some 15 years ago, and since then the camp’s residents have not received basic and essential services from the municipality, which is in charge of the area. Magen David Adom, Israel’s emergency medical service, does not enter Shuafat Refugee Camp, and in order to conduct testing for coronavirus, residents must cross the checkpoint and go to a nearby hospital.

Jerusalem Mayor Moshe Leon has objected to the Israeli government’s attempt to close the Shuafat checkpoint, yet many residents of the camp believe it may yet happen.

“The wall was built as part of a demographic policy whose goal is to push us out the city,” Ja’abri says. “It is clear to me and all those who live here that Israel doesn’t want us. That is why it is critical to demand that they build a testing center and isolation zone inside the camp. That way, if we are kept inside, we’ll have the infrastructure to deal with the crisis.”

Orphans facing pandemic

The spokesperson for Israel’s Health Ministry says there is no plan to establish isolation centers or implement testing on the other side of the separation wall. “Our starting point is that setting up stations in East Jerusalem is enough to serve these people as well. They need to pass through the checkpoint and get checked,” a spokesperson said. “If, God forbid, the checkpoint is closed, then this question will arise, and we will respond to it.” The added that he had no data on the number of COVID-19 patients in the camp, and that “the ministry does not do identification by nationality.” In other words, the ministry does not publish data on infections by neighborhood, only by city.

“This is a dangerous situation,” warns Abir Joubran Dakwar, an attorney with the Association for Civil Rights in Israel. “If the government decides to shut down the checkpoint, we won’t be able to know if doing so is justified for health reasons or if it is being done for political reasons.” According to Farad Zaghir, a doctor at a health clinic in Shuafat, there are currently no known cases of COVID-19 in the camp.

“It’s a ticking time bomb,” says Zaghir. “It is enough that one person gets sick and the virus can spread quickly. My clinic lacks alcohol, gloves, tests for workers, and protective masks. The staff has not yet undergone training for dealing with the coronavirus. The doctors in the camp do not have tools to deal with the pandemic. It is an emergency. I reached out to the Health Ministry a week ago but we still have not been given anything.”

[Update: On April 14, Shuafat Refugee Camp registered its first case of COVID-19]

While Israel does not provide the majority of necessary services to the Palestinian neighborhoods beyond the wall, it also continues to prevent the Palestinian Authority from doing so. Last week, Jerusalem Police arrested Fadi al-Hadami, the PA’s minister of Jerusalem affairs, as well as PA Governor of Jerusalem Adnan Ghaith on suspicion of helping to coordinate the PA’s coronavirus response in East Jerusalem, thus violating Israeli sovereignty. “On the one hand they do not give us rights, on the other hand they imprison anyone who tries to help fill the vacuum Israel has left,” Ja’abri says. “Now, as the pandemic explodes outside, this policy could very well end in catastrophe.”

Muatasim, a resident of Kufr Aqab, another Jerusalem neighborhood beyond the wall, says that he saw representatives of the PA walking through the streets and demanding residents remain home. “They also disinfected the neighborhood and did a lot of the work Israel neglected,” he adds. “Their involvement increased as the crisis grew. In the past I hardly saw them here.”

The PA recently launched a donation drive for food and equipment for Jerusalem families in need. The drive included a website where residents of the city could either request assistance anonymously or volunteer to donate. According to people in Shuafat Refugee Camp, many families from both the camp and Kufr Aqab have come to the site to ask for help, but Israel has repeatedly thwarted the drive’s success. “That’s why they arrested the governor of Jerusalem,” Ja’abri says.

Pinched between governmental neglect and the blocking of aid from the PA, the residents of the neighborhoods have been left orphaned in the face of a dangerous pandemic. The city has done very little beyond writing up people who violate the Israeli government’s lockdown directives, and, following a request by Israeli NGO Ir Amim, has disinfected some of the streets in Kufr Aqab.

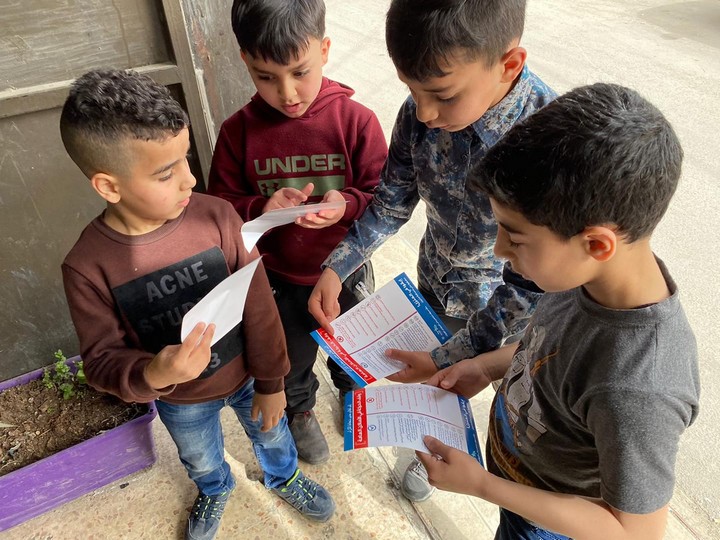

In light of this neglect, a number of independent organizations have emerged in the camp. “I hand out flyers with the Health Ministry’s instructions to people on the street,” Ja’abri said, “Our activity is dedicated to teaching children about the coronavirus, because they are the most attached to their grandparents.”

‘Dangerous and hostile at their core’

In recent weeks, local organizations and leaders in the camp have set up an emergency center, which has funded its own isolation center and protective equipment, and has taken a number of actions to disinfect public spaces and provide information on COVID-19 to the residents. “We were all united in the fight against the coronavirus,” says Aysar, one of the camp residents.

Approximately one third of Jerusalem’s Palestinian residents live in dire conditions and abject poverty on the other side of the wall. Munir Zughir, head of Kufr Aqab’s residential committee, wonders how it is possible that so many among the Israeli public are indifferent to what is happening in East Jerusalem. According to him, both the public and Israeli government representatives perceive the neighborhood’s population to be dangerous and hostile “at its core,” which serves as yet another “justification” for the neglect.

“I’ll give you an example,” Zughir says. “For a month now, people have had no income and the situation has been difficult. The same goes for many places, but this is one of the poorest populations in the city even without the coronavirus crisis.

“It’s not that there is nothing to eat, there are plenty of food donations,” he continues. “The main problem is gas and electricity. Some people don’t have money to pay bills and they sit in the dark. I asked the Ministry of Labor, Social Affairs and Social Services to send vouchers to 63 families in need. They spoke to me five days ago and agreed that one of their clerks would come to the neighborhood, walk around, and sign up the families. But the clerk did not come because he said it was dangerous, that there is gunfire, and so on. This is not true.”

“When armed Border Police officers enter the camp, it obviously raises tensions and the teenagers start throwing stones. But other government officials aren’t a problem,” Ja’abri says.

“The Israeli public is told a story about a hostile, uncooperative population,” he adds. “And yes, there is an antipathy toward Israelis that stems from years of oppression and conflict — this has political reasons. But as long as Israel controls the area then it is responsible and must find a way to act here, especially during a crisis.

“In my opinion, the way to deal with the crisis is through closer cooperation between the local leadership, which the residents rely on, and the Israeli authorities,” Ja’abri continues. “We are stretching out our hand. This is a matter of life and death, but we are repeatedly ignored, the neglect continues, and all we hear are slogans about our lack of cooperation.”

This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.