As a Palestinian living in Masafer Yatta, I have lived my entire life in an area that the Israeli army has declared a firing zone. When I was a young child, every single resident of our village, Tuba, was forcibly expelled from their homes. We were loaded onto trucks and lost everything. After we appealed to the Supreme Court, we were allowed to return to our homes until the court issued its final decision.

I have spent most of my life waiting for that decision. For the past 22 years, since I was seven years old, I have feared the day that our fate would be sealed. That day came to pass on May 4, 2022, when the Supreme Court ruled that the army may evacuate our villages and displace us — over a thousand residents — from our homes.

As I grappled with the devastating news of the decision, I was both saddened to think how this expulsion is simply the newest addition to my family’s long history of losing our home, yet also comforted by the knowledge that we have remained steadfast against attempts to remove us from our land in the past. Although my family has faced expulsion and the loss of our home before, we have not lost our connection to this land, nor have we lost our will to keep fighting for it.

As I thought more about what this decision would mean for me and my family — my parents, siblings, my wife and daughter — I knew that I needed to understand more about how my family has dealt with such realities of expulsion in the past. I wanted to understand both our people’s history of displacement and our history of steadfastness. As I think about the kind of parent I want to be to my daughter, I recall the example my father set for me and my siblings, and so I decided to interview him and hear his thoughts about where we come from and how this most recent court decision fits into our family’s story.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you introduce yourself?

My name is Omar Muhammad Abu Gendeh. I am 55 years old, and I live in the village of Tuba, southeast of Hebron, in Masafer Yatta, about 700 meters away from the Ma’on settlement. I live in my father’s cave, which he dug himself.

How long has our family lived in this area?

My father and mother used to live in a village named Al-Qaryatayn, which is today inside the Green Line. They were forced to leave during the 1948 occupation and so came to live in the eastern hills of the village of A-Tuwani, land on which the illegal settlement of Ma’on is now built. My father thought that his displacement had ended and that he would not have to leave his home again. In 1967, my mother gave birth to me in a cave on that same hill where my parents had settled. My parents lived there for 27 years, and my father made so many beautiful memories there.

Why were they unable to stay there?

The occupation never lets us remain in the place where we are born and raised. In 1967, my father started digging two caves and a well to collect water and build a home for his family in Tuba. He feared being displaced again and being left out in the open. In 1980, my father’s fears began to become reality. The occupation built a bypass road [for settler use] now called Road 317. In 1982, they began building the settlement of Ma’on and the other settlements that are located along the bypass road. This meant that they now controlled a significant amount of land, including pastoral and agricultural land that we had planted, which was taken from us and annexed to the settlement.

Shortly after, settlers planted crops on the hill on which we lived, so we had to move to the village of Tuba. This was my father’s second experience of displacement, and the first experience continued to live within us. But this second experience had its own cruelty because we could see the place where we were born and grew up, but were forbidden from entering it. It’s a hard feeling, and it hurts on the inside.

What was life like in the early days after you moved to Tuba?

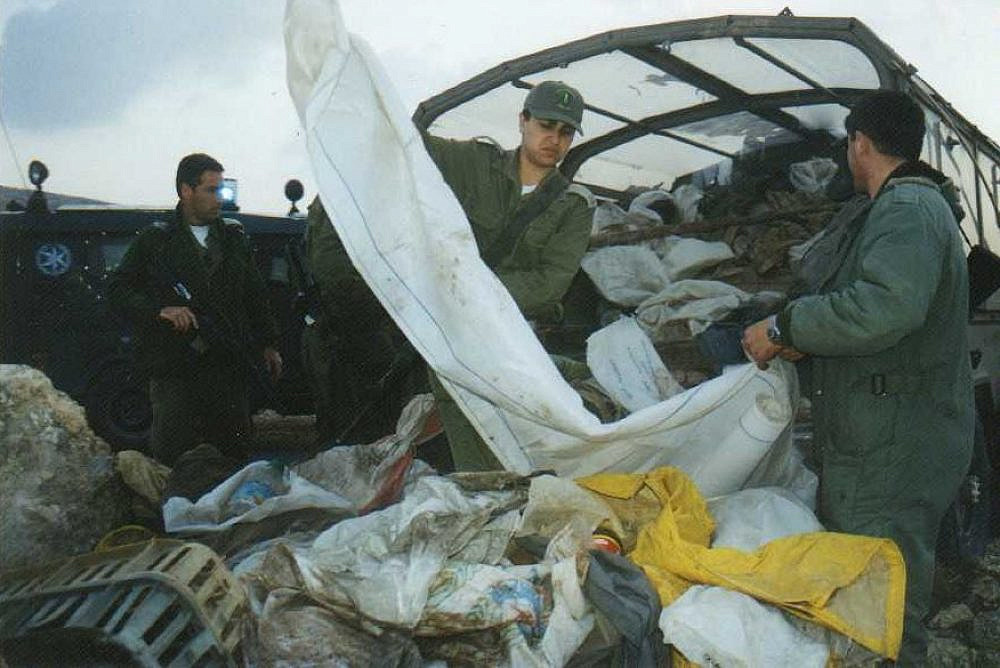

The suffering began to increase daily with accusations and attacks by settlers and the wide scale, rapid confiscation and annexation of our land to the settlement. In the early 1980s, Israel declared 12 villages in the Masafer Yatta area — including our village — a military firing zone, which they named “Firing Zone 918.” A year later, they began to demolish villages, including Jinba and others. In 1997, in order to force the residents to leave their land and their homes, the Israeli Civil Administration decided to demolish population centers in Masafer Yatta, and our village was the first.

Everything was destroyed, except for the cave in which I now live. They didn’t refrain from demolishing this cave out of kindness for us or in order to leave it as a shelter for us, but rather because it was full of food for our sheep. Because they couldn’t empty it, they left it and instead confiscated everything. They even confiscated our kitchen utensils and dumped them behind Bypass Road 317.

What do you remember from that day when they demolished our village?

I remember that day very well, in all of its cruel and catastrophic detail, as tents and caves belonging to community members were demolished. We realized that there was one pot that they had not confiscated, and we used it to cook food for my children and for my brother Ibrahim’s family. The next morning, we went to find our things that had been thrown out onto the street. We began to remove the rubble of our old homes and rebuild new homes. Rebuilding our village meant starting from scratch, and it took us two years to do.

What happened after you finished rebuilding?

The occupation did not allow us to rejoice in the rebuilding of our village and our homes. On the second day after we had finished, the Israeli Civil Administration [responsible for managing the day-to-day life of millions of Palestinians under occupation] came and said that we must evacuate our village within 24 hours. If we refused to leave, they explained that they would come and demolish the village again, arrest the youth, and confiscate our sheep and the rest of our belongings from our homes.

Despite their threats, we did not listen to them. Every day, early in the morning, I would go to hide all of our cooking utensils in the valley out of fear that they would be confiscated, and in the evening, we brought them back to cook food. We slept outside of the village with our sheep because we feared that the sheep would be confiscated and the young men arrested.

This went on for a week. At night, there were only women and children in the village, and so the settlers would come to frighten them, singing and dancing inside the village and shooting in the air. During the second week, the Civil Administration came and arrested my older brother, Ibrahim. After my brother’s arrest, and in order to put pressure on us to leave, they continued to come at night to arrest people or confiscate sheep, frightening women and children as they searched inside the tents and caves for men and their flock. My brother was detained for a week, and when they saw that we had finally left, they released my brother.

What happened after you left the village?

We went and lived in the village of A-Tuwani for four months, during which time, with the help of foreign and Israeli solidarity activists, we filed a petition with the Israeli High Court of Justice, a body that carries out no justice for us as Palestinians. There was a decision that we could temporarily return to our village on March 11, 2000.

However, our suffering increased at the beginning of 2002, when they closed the main road that connects our village and four other villages to the city of Yatta, which is where we must go for health and education services, purchasing items for our daily needs, and selling our cheese and dairy products. It was even worse for school children, who had to travel great distances to get to school. The daily journey was long, through rugged mountains and valleys to reach the schools. A trip that, with the main road, had taken half an hour, now took two hours.

What was life like after being allowed to return to Tuba?

The intensity and frequency of settler attacks on the village increased, including the destruction and burning of crops, which they carried out against my crops in 2006. They burned all of my crops after I had finished harvesting, a common form of attack. Attacks also increased against our sheep, who were beaten and killed after being stabbed by settlers, something that happened to my brother’s and my neighbor’s sheep. At other times, we were arrested, made to pay fines, and had more of our pastoral and agricultural lands confiscated.

Last month, I was arrested and fined after a settler came forward and tended crops that I had planted. My son, nephew, and neighbor were then arrested at night and imprisoned for three days before paying a fine to be released. There are so many attacks that took place that I can no longer remember all of them. One would need to write a book to recount all of them.

What do you think of the most recent Supreme Court hearing?

On March 15, 2022, I went to a Supreme Court hearing in Jerusalem about our displacement. On May 4, we received the news that the decision was to displace us – conclusively and definitively. Since the decision was issued, harassment against residents happens every day — people are arrested and beaten, vehicles are confiscated, roads are closed, and agricultural land is bulldozed. But we will not leave our land or our village, and we refuse to experience again the torment and cruelty of displacement. No matter what, we will stay, even if they demolish all of our homes. We will remain on the rubble, and we will not leave our land. We will not allow them to cast us aside as they did to our parents and grandparents.