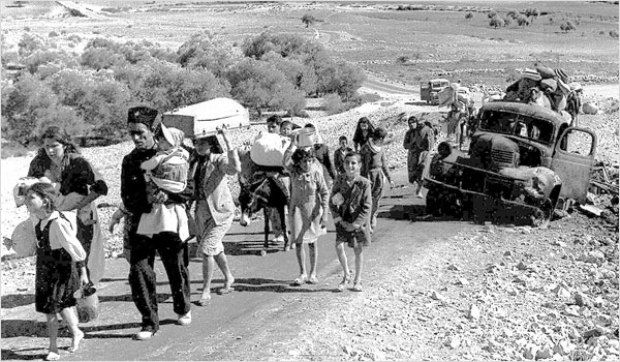

Paradoxically, the overbearing stance of Israel’s Nakba law had significantly increased public interest in the Nakba

By Eitan Bronstein

The Nakba Law that passed at the Israeli parliament recently has a single primary goal: to categoricaly hide the Nakba: Hide it, do not learn about it, do not remember it, and do not take responsibility for its consequences. Put it, word and memory, back and deep into the Pandora box from which it emerged during this past decade in Israel. The illusion in passing this law is that it is possible to lock it away and bury the key at the sea along with other threats buried there recently. Paradoxically, this law, in its overbearing stance, had actually significantly increased public interest in the Nakba.

The language of the law–which allows the state to withdraw state funds from institutions who would mark the Palestinian disaster–refers in its written clause only to the “public” or “state supported” institutions organizing events to mourn at the Israeli Independence Day, but within its message it aims to create an atmosphere of terror against anyone who dares to touch the event that established the Jewish state. This law does scare people; it terrorizes them. Zochrot, which deals with the Nakba, constantly receive requests from Israelis who want to learn about the Nakba, but are afraid; in their fear they ask if learning about the Nakba is still allowed. Participants at teacher’s workshops and trainings on how to teach about the Nakba at their classes, are more afraid to do so openly than ever before. Last teacher openly interviewed about teaching the Nakba received a threatening letter from the Ministry of Education. Facing this reality, Zochrot had no choice and decided to toe the line to limit any chance of exposure of the hundreds of trained teachers who taught about the Nakba. Protecting the teachers and their livelihood is first priority for us.

The most reasonable response to this law that seeks to prohibit commemorating the Nakba at the Israeli Independence Day is to stand up and take civil disobedience action, commemorating the Nakba at the upcoming Independence Day. This is an unprecedented and disdainful scenario in law to expressly forbid citizens of remembering their past. For one fifth of the citizens – the Palestinians – this law forbids them from remembering their own tragedy, their own dispossession. This racist law is so blatantly anti-democratic that the response to it by any decent human being should be in the unmistaken opossition by physically being at the Nakba commemoration in the Israeli Independence Day.

(If the word Nakba is the barrier to seeing the ramifications of this law), imagine a hypothetical situation in which one of the leaders of the city Tel Aviv – Jaffa offers to drastically limit the annual gay pride parade that has become tradition in the city. He or she would argue that this event harms the sensibilities and feelings of many and therefore should be limited to a closed compound, such as the port of Tel Aviv. Such a position would encounter massive outcry. If, for whatever rationale, this offer was to be accepted many would be joining the Tel Aviv gay pride parade in solidarity and protest. Many, among them people who aren’t that excited about the parade itslef, but are concerned with the propsoed politics and aesthetics, would join it personally to convey a clear message to city leaders about the rights of all citizens. In fact, something similar did happen when many people from Tel Aviv joined that same march in Jerusalem when it was limited to closed stadium.

The situation with the Nakba Law is much worse than that hypothetical scenario. Israeli state law seeks to prohibit the Nakba memory anywhere within the Jewish state borders. Such a law demonstrates a grave injustice to all citizens, and in partciualr, to one fifth of the state’s population. The right thing, the only decent thing Israelis should do is join en masse the central march organized by the Association for the Defence of the Rights of Internally Displaced Palestinians in Israel, to the destroyed villages of al-Damun and Rweis, near Tamra. Every year several hundred Jews join the thousands of Palestinians at that march, but the potential number of Jews to join it is much higher.

True, there are obvious reasons for which many decent Israelis have so far refrained from participation in the main event commemorating the Nakba in Israel in the last fourteen years. Incidentally, the Nakba Day internationally is held on May 15 and only in Israel it’s commemorated on the Hebrew date of the state founding.

For Israelis, commemorating the Nakba at The Israeli Independence Day, seems like a provocative act, one that seeks to place clearly and symbolically the Nakba in opposition to the Independence. Even if this opposition is true to some extent, it is important to know that historically the origin of commemorating the Nakba at The Israeli Independence Day has to do with the Israeli occupation of 1948, i.e. the Nakba itself. After the expulsion of the Palestinians more than 20,000 of them remained within Israel’s borders. Hard to say that they were /are treated as citizens (with full meaning of citizenship) as they were subjected to military rule almost until the war of 67. During this period, the only day of the year in which they could move freely in the country, without a permit from the military governor, was The Israeli Independence Day. Many of them have used this freedom to visit their destroyed villages, which created the tradition of visiting their lost homes at the Israeli celebration day, remmebringa and commemorating their catastrophe. Only fourteen years ago (for reasons I won’t elaborate here) the first “Procession of Return” was organized as a demonstrative and political event to commemorate the Nakba.

The event itself is an impressive national Palestinian performance. Israelis, even those who belong to the peace camp, do not feel at ease surrounded by Palestinian flags and hearing speeches in Arabic for an extended period of time. Perhaps it is prime time to get over this irrational discomfort and live for few hours the minority experience? It seems to me that this lesson in itself is not a bad lesson to learn. Since Zochrot and other organizations joined this event, nine years ago, Hebrew language became present in part of the speeches.

Most difficult challenge for most Israelis is the idea of the right of return. At this procession, while commemorating the Nakba, the call for recognition and implementation of the right of return is unequivocal, not as a mathematical (and a racist) trick as with the Geneva Initiative; not a “symbolic recognition” of the right of return, and certainly not as only “listening to other’s pain”. The Palestinians are telling us loud and clear: the right of return must be accepted in order to have a real chance for peace.

On my part, I understand the recognition of the right of return and its actual realization as an historic opportunity for us to live here as equal citizens and not as colonizers.

I’m calling here on those who (still) do not recognize the right of return: Let’s show solidarity with the Palestinians even though you do not recognize this basic right. In a new reality, with the Nakba law and other anti-democratic laws in place, you might wake up too late to commemorate the Nakba on Israeli Independence Day. Thus, rather than fear the law on one side and the right of return on the other, we can actively and collectively cope with the Nakba and its consequences for the sake of our mutual future.

Eitan Bronstein is the Founder and Director of Zochrot, an Israeli NGO dedicated to preserving the memory of the Nakba.

English editing: Rula Awwad-Rafferty. This article was originally published in Hebrew in Haoketz on May 9, 2011.

Read more in +972 Magazine’s Remembering the Nakba project:

Joseph Dana: Occupation & Nakba: Interview with Ariella Azoulay & Adi Ophir

Yossi Gurvitz: Rightwing group publishes Nakba denial booklet

Dahlia Scheindlin: Nakba Law: Is it time for civil disobedience?

Noam Sheizaf: Why Jews need to talk about the Nakba