In the first months of the protests against the judicial overhaul, it seemed that the mere threat of Israeli Air Force (IAF) pilots ceasing to show up for reserve service was the movement’s doomsday weapon. Many estimated and predicted, myself included, that as soon as Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu realized that he may be left without an effective air force, he would fold.

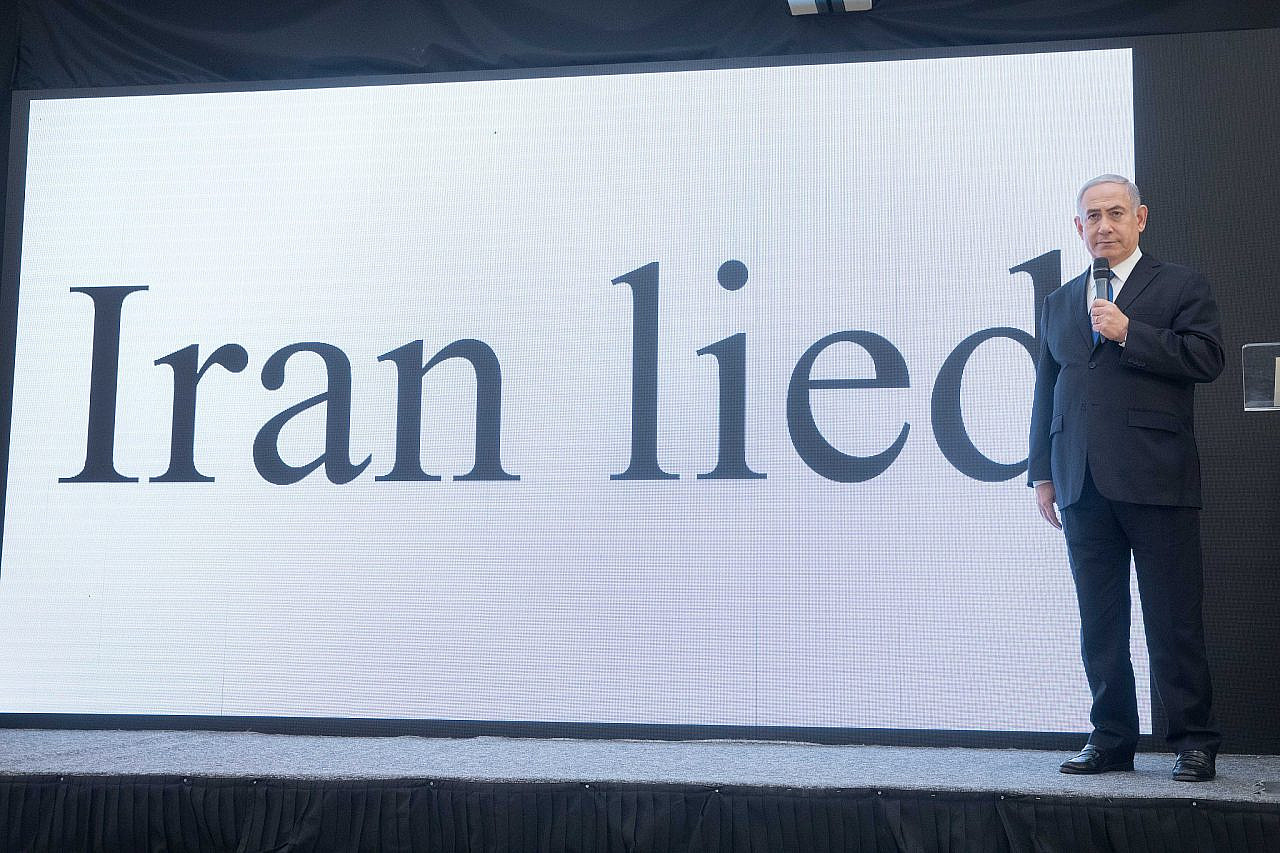

After all, Netanyahu has spent decades warning both Israelis and the international community about a supposed Iranian threat, explaining that Israel needs a strong air force to “maintain its freedom of action“ against Iran and the Islamic Republic’s proxies in Syria. Without pilots ready at any moment to jump into the cockpit to bomb Damascus or Tehran, his entire security-political thesis was supposed to collapse.

It was the fear of widespread conscientious objection in the IAF that pushed Defense Minister Yoav Gallant to express reservations about the overhaul in March, pushing Netanyahu to freeze the legislation. The prime minister then announced he would be firing Gallant, only to never go through with it.

When the government brought forth legislation to annul the “reasonableness standard,” and the threats by reservists reached a fever pitch, the right went into denial. “There is no protest by the reservists, there is a negligible number of dozens of active reservists who may not show when they are called up,” wrote Brig. Gen. (Res.) Oren Salomon, a member of the right-wing Israel Defense And Security Forum, in the settler newspaper Makor Rishon in the run-up to the vote.

A few days after Salomon’s article was published, 1,142 pilots and IAF personnel announced that they would stop their volunteer duty in protest. It is difficult to know the exact number of reservists who have since stopped reporting for duty, but it is clear that the effect is noticeable.

In a conversation with his pilots about a week ago, IAF commander Tomer Bar admitted that the preparedness of his force had been diminished. In an interview with Haaretz published last week, Amikam Norkin, until a year ago the commander of the IAF, said that the force has “until the end of the year” before it sees a significant decline in fitness.

But precisely when the damage to the IAF’s competence becomes real, precisely when the ability to bomb Iran, Syria, or Lebanon grows ever more distant, Netanyahu is giving the impression that he has no intention of folding. On the contrary, he has announced that he intends to press ahead with the next stage of the judicial overhaul — a law that will change the composition of the Committee for the Appointment of Judges, which is considered by the protest movement to be the centerpiece of the reforms — and has also hinted that he may not comply with a Supreme Court ruling that strikes down the annulment of the reasonableness standard.

Rather than stopping, Netanyahu seems to be racing toward a constitutional crisis the likes of which Israel has never known.

A decades-long bluff

There could be several explanations for this behavior. Netanyahu understands that he will have to stop the legal overhaul eventually, but he does not want to show his cards and appear weak. Only through a show of strength will he be able to maintain his far-right coalition, which seems very loose today: from the Haredi parties who insist on enshrining exemption from conscription for their communities; to National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir, who demands constant attention like a disobedient child; to Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who practically wears his racism on his sleeve; to Yariv Levin, who doesn’t like when people badmouth his reforms.

A second possibility is that Netanyahu views the crisis with the army as part of his “war on the elites,” which he has engaged in since he entered Israeli politics in the mid-1990s. When Netanyahu was first elected prime minister, in 1996, the army’s top brass was fully committed to the Oslo process. His loss in the 1999 elections can be at least partially attributed to the mobilization of the military elite against him — including his victor, Ehud Barak, who went from IDF Chief of Staff to chairman of the Labor Party.

The relationship between the army and Netanyahu has always been strained, and Netanyahu has often taken pains to make sure the public knows that it was the army that stopped him from implementing his policies — from bombing Iran to carrying out an even more extensive ground offensive on Gaza during “Operation Protective Edge” in 2014. Now, Netanyahu can use the opportunity to settle the accounts with the military elite. And in the eyes of much of the right, the pilots have become a symbol synonymous with the elitism of the protest movement.

A third explanation for Netanyahu’s behavior cuts to a more fundamental issue. Today, Israel uses its military power not to defend against an Iranian or Syrian threat, but to control the Palestinians in the occupied territories; this makes it possible to understand why Netanyahu is not so moved by the IAF’s “loss of fitness.” In fact, the main goal of the army today is to act as the policing army of occupation, and for that there really is no need for sophisticated aircraft.

It is no coincidence that the army has been turning more and more to drone warfare over the last decades. “Instead of relying on pilots, we need to develop a drone corps,” was the title of a recent article by Yair Amar, published last month on the right-wing site Srugim.

The goal, according to Amar, isn’t strictly military — it is also political. Amar’s idea of establishing fleets of combat drones is meant to not “leave too much power in too few hands,” by which he means taking political power from the pilots who oppose the right. But Amar’s move also makes operational sense: “At a significantly lower cost than anything the air force can offer, for the price of individual F-35 aircraft, the IDF can establish one of the most advanced and well-equipped missile forces in the world,” he wrote.

He is right. To bomb Gaza there is really no need for F-35s. Unmanned aircrafts operated at the push of a button from an air-conditioned command room in Tel Aviv are enough.

Netanyahu likely knows that there is no real Iranian threat to Israel, certainly not an immediate one. After all, Israel has been bombing Iranian targets in Syria for almost a decade, senior officials of the Iranian nuclear system were assassinated in Iran in dramatic operations attributed to the Mossad, and during this entire period there was no direct Iranian attack on Israel. The Syrian army is a non-existent entity, and an attack from Egypt or Jordan is not on the cards. Hezbollah is not expected to attack either, as long as Israel does not attack Lebanon.

Netanyahu no longer needs the IAF, one of the most powerful in the world, to continue to promote his ultimate goal since he entered Israeli politics: deepening Israeli control between the river and the sea, erasing the Green Line, and quashing any semblance of Palestinian nationalism.

Most read on +972

Netanyahu’s problem is that he cannot admit this simple truth. After all, if he says these things openly, how will he continue to promote the idea that “Iran wants to wipe Israel off the map,” which he has woven into almost every interview and speech for the last 30 years? How will he continue to portray himself as the only leader capable of saving Israel from destruction?

None of this means that the growing refusal to serve in what some protesters are now calling an “army of a dictatorship” is meaningless. Mass conscientious objection has the power to shatter Israel’s image as a superpower, and it certainly has enormous political significance on Israeli society, reflecting the broken “social contract” between Israeli Jews and the state. Yet at the same time, the breakdown in the IAF also exposes Netanyahu’s cynical, decades-long bluff on Iran. For that alone, the refusers should be commended.

This article was originally published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.