This article was published in partnership with Local Call.

Since the establishment of the Arab-led Joint List in 2015, and especially amid the electoral stalemate that has characterized Israeli politics since the election for the 21st Knesset in 2019, there has been increasing debate in the Arab political arena over whether to recommend candidates for Israeli prime minister as they jostle to form a viable governing coalition.

The current iteration of this debate began in the aftermath of the Joint List’s recommendation in September 2019 to then-President Reuven Rivlin — which was hailed as historic — that Benny Gantz be tasked with forming a government. Despite disappointment in Gantz’s subsequent decision to form an alliance with his rival Benjamin Netanyahu, the Joint List supported Gantz again in 2020. And in 2021, most of the parties constituting the Joint List recommended Yair Lapid for the job.

Now, looking ahead to the fifth election in just under four years on Nov. 1, there is a growing hesitancy within much of the Palestinian community in Israel with regard to endorsing a candidate for the premiership. This is accompanied by a growing skepticism toward participating in the Israeli political system altogether — despite the threat of Netanyahu and his far-right allies inching closer to the 61 mandates needed to form a government.

With the disintegration of the Joint List years in the making, the various parties that once comprised it now represent distinct positions on the question of full political participation. The Islamist Ra’am, which split from the list ahead of the 2021 election, broke new ground by becoming the first independent Arab party to join an Israeli government (albeit without a ministerial portfolio). Since the collapse of that coalition in June, the party has continued to position itself as part of the “change camp,” with leader Mansour Abbas now ruling out supporting Netanyahu for the premiership.

In contrast, the nationalist Balad, which is running independently after separating from the Joint List last month on the eve of the submission deadline for electoral lists, is now expressing an unequivocal refusal to partake in the “Israeli game,” save for acquiring parliamentary seats as an opposition party.

Hadash and Ta’al — the two Arab parties that are still running together in this election — are exhibiting more caution in their public statements on the question of recommendation. Ayman Odeh, the leader of the left-wing Hadash who also heads the combined list, said last month that Lapid and Gantz will have to “do a lot of work to get the recommendation of the real left, of the real democrats.”

Odeh tends to use his speeches to emphasize the dangers posed by a Netanyahu-led government with the support of the extreme-right Itamar Ben-Gvir and his allies. He also critiques the Bennett-Lapid “government of change” that, in fact, demolished more Palestinian homes, killed more Palestinians in the West Bank, and allowed more provocative visits of Jewish worshippers to the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif than the last iteration of the Netanyahu government. The leader of Ta’al, Ahmad Tibi, similarly stresses the dangers of Netanyahu’s possible return.

Odeh has been making the case for increased Arab representation in the Knesset, and the active participation of Palestinian citizens, using an idea rooted in Islamic law: “It is better to prevent corruption than to make gains.” But this is not a new argument: Arab parties have always acted on the principle that “there is bad and there is worse” in order to justify backing candidates on the Zionist left.

In fact, this practice precedes Hadash’s famous recommendation of Yitzhak Rabin for the premiership in 1992 — from which Arab parties continue to draw legitimacy for similar recommendations to this day. The real question, however, is whether Palestinian citizens will still believe in this principle come election day next week.

To recommend or not to recommend

Contrary to popular belief, Arab and non-Zionist parties have recommended candidates for the premiership well before 1992. A few years after the “upheaval” election of May 1977 — in which Mapai (the precursor to the present-day Labor party) lost power for the first time to Menachem Begin’s Likud — the election for the 10th Knesset in June 1981 produced almost an exact tie: Shimon Peres’ center-left Alignment won 47 mandates, while Likud won 48.

In order to prevent the return of the right-wing Likud, the Arab-Jewish Hadash, like the Zionist-left Ratz (a precursor to today’s Meretz party), was ready to recommend Peres. But Israel’s then-president, Yitzhak Navon, gave Begin the first attempt at assembling a coalition, which he succeeded in doing with the help of other right-wing and religious parties.

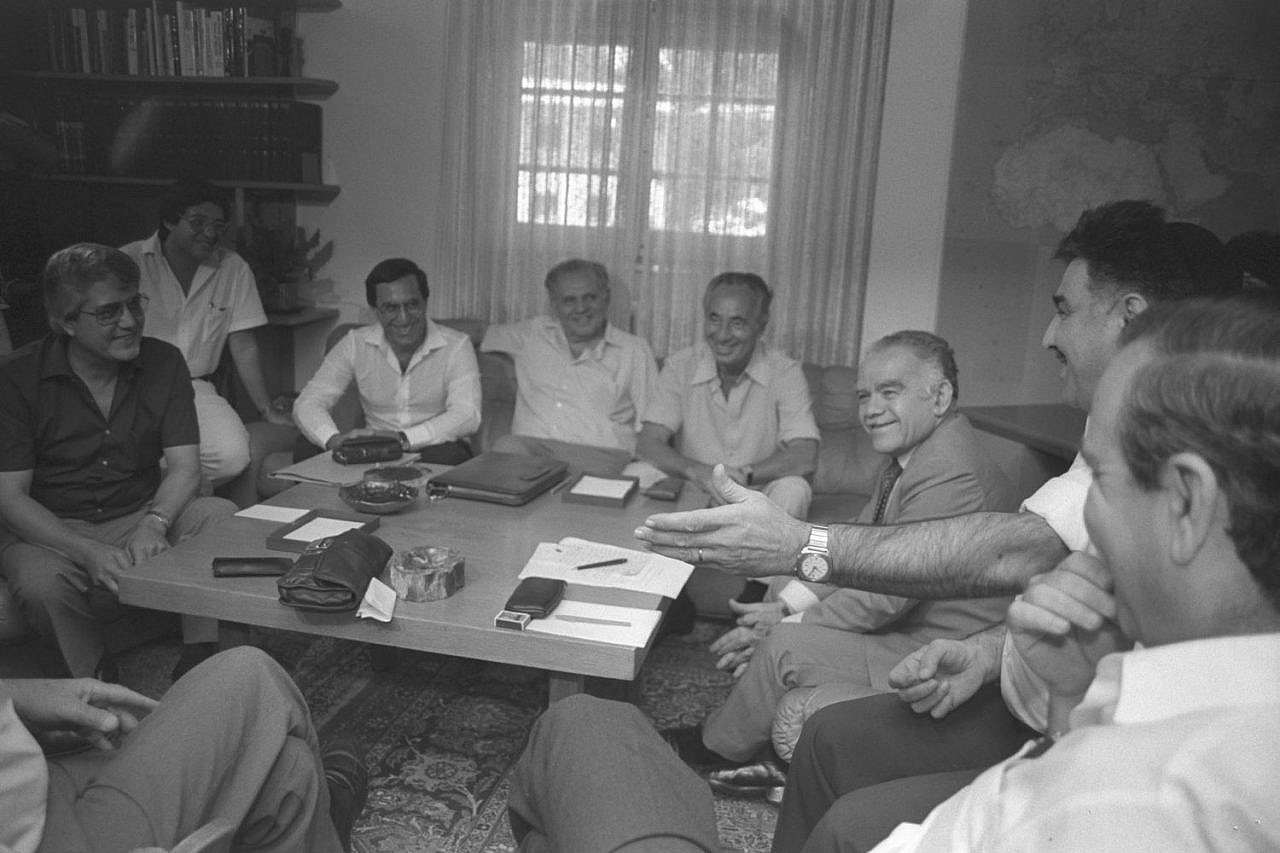

The election for the 11th Knesset in 1984 produced another tie between the political camps, but this time the balance was flipped: Alignment won 44 mandates, while Likud, now headed by Yitzhak Shamir, won 41. With both camps struggling to establish a government, Hadash — led at the time by Jewish MK Meir Vilner, though most of its voters were Arab — recommended Peres for the premiership to President Chaim Herzog. The party’s statement highlighted the role of Israel’s military occupation in the country’s internal crises and called for the state to change its policies, while emphasizing the limitations of a unity government and expressing explicit opposition to the Likud government.

(Nati Harnik/GPO)

However, it turned out that Hadash’s “recommendation” of Alignment leader Shimon Peres was too indirect, and did not fit within the protocols set out by the president. After President Herzog requested further clarification, Hadash MK Tawfiq Toubi stated: “We’re not supporting [Peres], but rather advising or recommending in the current circumstances that you charge one of the MKs from Alignment with the task [of assembling a government]. Later on, we will clarify our stance on the government, once it is formed.”

Hadash was not alone in its recommendation. The Progressive List for Peace — a short-lived Jewish-Arab party in which the historical roots of Balad can be found — also backed Peres following the 1984 election. In the end, however, a unity government was formed with a rotation of the premiership between Peres and Shamir.

The recommendation question also applied to the Israeli presidency. One year earlier, in 1983, Hadash played a decisive role in the presidential election, in which Supreme Court Justice Menachem Elon, backed by Likud, ran against Alignment candidate Chaim Herzog. The president is elected by a parliamentary majority, and given the 64-seat coalition that Begin commanded at the time, Elon’s victory looked like a mere formality.

In order to win, the Herzog campaign needed to secure defections from the Likud-led coalition. But there was another problem: Hadash MK Tawfiq Ziad was in Japan and due to be absent for the vote. Former Alignment MK Uzi Baram, who ran Herzog’s campaign, told Local Call that Hadash was so determined to defeat Likud’s candidate that the party ordered Ziad to return from Tokyo. Herzog won the election with a majority of 61 MKs (58 voted against and one abstained), and Baram and Ziad became friends.

MK Ayman Odeh told Local Call that this story only illuminates how far Jews and Arabs have moved away from the idea of partnership, and the extent to which hate and racism have spread through the country.

The Arab world intervenes

The story repeated itself in the election for the 12th Knesset in 1988, as Likud won 40 seats compared to Alignment’s 39. Hadash won four, while the Progressive List and the Arab Democratic Party — which split from Alignment ahead of the election over the latter’s policies during the First Intifada — won one mandate each.

Hadash, the Progressive List, and the Arab Democratic Party all recommended Peres for the premiership — based on a broad consensus to try to prevent the establishment of a Likud government — on the condition that Peres commit to closing the social and economic gaps between Jewish and Palestinian citizens. But again, just as in 1984, a unity government was established.

When Peres tried to subvert the unity government by establishing a minority government, in a move infamously known today as “the dirty trick,” Hadash signed an agreement with Alignment supporting the move in exchange for the creation of a “ministerial committee that will work to reduce the gaps in the Arab sector,” as reported in Haaretz on June 5, 1990.

Peres’ attempt ultimately failed, but it is interesting to see that the agreement formulated between Alignment and Hadash in 1990 is almost identical to the civic provisions in the agreement between Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid and Ra’am from 2021. The 1990 agreement, however, also contained a number of political provisions, including a reference to the peace process in the region, the fostering of friendship and reciprocal relations between Israel and any country seeking peace, and a deepening of relations with the United States alongside a renewal of diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union.

The decision by Hadash and the Arab Democratic Party to recommend Yitzhak Rabin for the premiership, in the aftermath of the 1992 election for the 13th Knesset, was easier; the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), led by Yasser Arafat, had explicitly requested that they do so, despite Rabin having commanded the Israeli army to “break the bones” of Palestinians amid the outbreak of the First Intifada just a few years earlier.

In his memoir “The Challenge for Peace,” former Arab Democratic Party head Abdulwahab Darawshe detailed the secret meeting that the PLO held with Arab leaders in Israel on the eve of the election, the goal of which was to encourage Palestinian citizens to vote in full force, and to unite, as much as possible, the Arab parties into one list that would support the Labor party. This occurred at the same time as secret talks between the PLO and Israel were underway in Oslo.

January 19, 1995. (Ya’acov Sa’ar/GPO)

The current president of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas, was then responsible for the PLO’s Israel desk, and it was he who managed the meetings with the Arab leadership in Israel through the Palestinian ambassador in Morocco, Wajeeh Qassim.

The efforts to unite the Progressive List for Peace, then under the leadership of Mohammed Miari, with the Arab Democratic Party, under the leadership of Darawshe, were unsuccessful. Egypt then intervened in the talks by organizing a meeting in Cairo with Darawshe, Miari, Ibrahim Nimer Hussein (then-head of the High Follow-Up Committee), Mahmoud Abbas, and Osama El-Baz, a state advisor to Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak. This effort also failed.

Then, a few days before the 1992 election, Mahmoud Abbas sent an urgent and threatening fax to Miari, in which he wrote, “I am instructing you to terminate your list’s participation in the elections.” Miari confirmed this story to Local Call. He recalled being at Ben Gurion Airport waiting to welcome Edward Said, who was arriving from the United States, when “members of the Progressive List called me and told me about the message from Abu Mazen [Abbas]. I used the disparaging Arabic proverb, ‘May he cast the telegram into the water and drink it,’” Miari said.

Sacrificing past and future for the present

In the end, the Progressive List did not pass the threshold required to gain a Knesset seat. The Arab Democratic Party won two mandates, and Hadash won three. Both parties recommended Rabin for the premiership, and later also gave his government a safety net in the form of a so-called “blocking bloc” which, while not officially part of the coalition, voted with the government on most issues.

An agreement signed between the two parties and Rabin included a commitment to peace with the Palestinian people; repealing the law preventing Israelis from meeting with the PLO; closing the gaps between Jewish and Palestinian citizens through the budgets of local authorities, social security grants, and more; establishing a university in Nazareth; and legalizing unrecognized Arab villages in the Naqab/Negev and the Galilee.

Rabin succeeded in passing the Oslo Accords through the Knesset in September 1993 with the support of a majority of 61 MKs, among them Arab lawmakers. Two decades later, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, then still the head of Likud, followed in Rabin’s path when he passed the Gaza Disengagement Plan with the support of Arab MKs in August 2005.

From a historical perspective, it is clear that the Arab parties have done much to integrate themselves into the Israeli political system, just as Palestinian citizens have done in Israeli society more broadly. They frequently forwent parts of their Palestinian national narrative, paid symbolic and moral costs, and sacrificed many aspects of their past and future for the sake of the present, to move toward real partnership and, for some, even Israelization. So far, however, all this was done without getting anything in return that would render their citizenship full or equal.

A version of this article first appeared in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.