The opening of the Knesset’s summer session last month has renewed a perennial debate among Palestinian citizens of Israel: whether or not there is anything to be gained from electing Arabs to serve in Israel’s parliament.

For Palestinian members of Knesset, the resumption of parliamentary business could not have come at a more challenging time. There has been almost wall-to-wall support among their Jewish counterparts for the Israeli army’s massacres in Gaza over the last eight months. Government ministers are competing over who can make the most racist statements. A McCarthyist crackdown on free speech since October 7 has seen hundreds of Palestinian citizens arrested for as little as “liking” a post on social media. All the while, the state’s inaction has led to record levels of violent crime afflicting Arab communities.

At the same time, global public opinion continues to turn against Israel, with large pro-Palestine demonstrations disrupting campuses and capitals worldwide. The first signs of real international pressure have also emerged: the United States and other Western states have imposed sanctions against violent Israeli settlers; more countries are recognizing Palestinian statehood; and the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court has requested arrest warrants for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, alongside three Hamas leaders.

Amid this political whirlwind, is there any space left for Palestinian Knesset members to make a meaningful difference? Or, as a sizable chunk of Palestinian society in Israel has long argued, is it better to boycott the elections altogether?

“There is no doubt that this Knesset session will be difficult and tense,” Ahmad Tibi, a long-serving Arab MK and chairman of the Hadash-Ta’al parliamentary slate, told +972. “Incitement [against Palestinians] has broken records. The killing, the bloodshed, and the war weigh heavily on each of us personally, as well as on the functioning of the Knesset. There are constant attempts to restrict the moves of Arab MKs — they are attacked for everything. Even if no reason can be found, [other Knesset members] invent one, especially the delusional backbench MKs in the coalition.”

Still, despite the rampant incitement against Arab MKs — who are regularly branded “terror supporters” by many of their Jewish counterparts — Tibi insists that they have a crucial role to play on behalf of their constituents. “It is important to be there despite the challenges — indeed, because of them.”

‘The master’s tools’

But there are plenty of Palestinians in Israel who disagree. Voter turnout in Arab localities was just over 50 percent in the last election of November 2022, compared to 70 percent nationwide, and some Palestinian groups are aiming to make sure it’s even lower next time around.

Louay Khatib is one of the leaders of Abnaa al-Balad (“Sons of the Land”), a political movement that has opposed participation in Israeli elections for decades. “For Israeli governments past and present, the purpose of having Arabs in the Knesset is not to help advance [Palestinian] rights, nor does it stem from a democratic outlook,” he told +972. “It is merely intended to improve Israel’s image in the world.

“We have no place as Arabs in the Knesset,” Khatib asserted. “The master’s tools were created to maintain the master’s house. The Knesset will not serve our existence or our goals.”

Khatib argues that contesting Knesset elections turns Palestinian politicians “into people without a backbone,” and weakens Palestinian society in Israel. He points to the example of Mansour Abbas, whose Islamist party Ra’am split away from the Joint List of Arab parties in 2021 to join Israel’s governing coalition — the first time in Israel’s history that an independent Arab party was part of the government. Abbas, Khatib noted, “has reached a point where he blames only Hamas and not Israel, despite the crimes it is committing in Gaza.”

Amid the war in Gaza, Khatib believes that the Palestinian presence in the Knesset has allowed “people who support them to choose a ‘soft’ path, to settle for a statement here or there, instead of protesting and raging.” By contrast, Khatib sees powerful shifts abroad: “Look at the demonstrations all over the world [for Palestine]. European countries recognize Palestine, Israel is becoming increasingly isolated, and we here are not doing anything significant, going on with life as usual.”

Khatib goes as far as to argue that Israel’s current far-right government actually serves the Palestinian cause. “Israel is isolated because the extremists are in power, and this is consistent with Palestinian interests,” he explained. “In the past, we had to work hard, but now [Itamar] Ben Gvir and [Bezalel] Smotrich did the work [for us]. They exposed the true face of Israel. If this government is replaced by another government that is more accepted by the rest of the world, Israel will return to its status as the world’s spoiled child.”

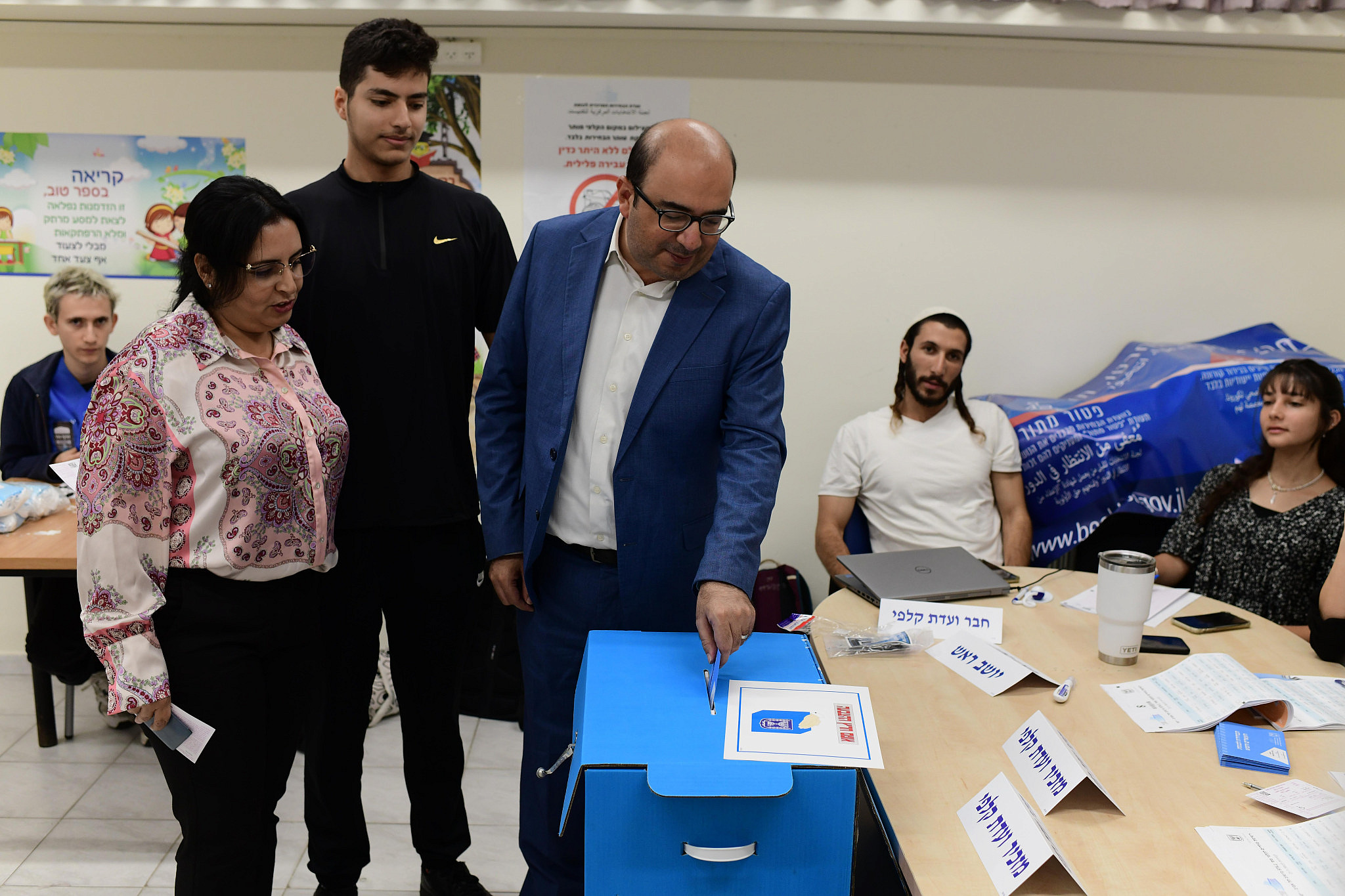

These discussions are not just taking place within Palestinian civil society. Sami Abu Shehadeh leads the Balad party, which fell just below the electoral threshold to enter the Knesset in the last election after more than two decades in parliament. According to him, the debate about electoral participation will come up at the party’s conference this weekend, as its membership considers how it can have the greatest impact.

“There are voices in Balad saying that it is clear that the right wing controls Israel, and therefore there is no point in even fighting it in the Knesset,” Abu Shehadeh said. “Other voices argue that this situation increases the importance of being present there.”

Either way, he noted that Balad has always been clear about the limitations of parliamentary work. ”The existence of an extreme right-wing government, or any other government, does not affect our vision as we do not expect much from the Knesset anyway.”

For Abu Shehadeh, various factors must be taken into account before arriving at a decision: the situation in Gaza, the political landscape in Israel, the problems facing Palestinians in Israel (from rising crime to an economic crisis), and whether or not there are “partners” for their agenda among Jewish-Israeli society.

Abu Shehadeh also leveled criticisms at the other Arab party leaders and their agendas. First, in a reference to Hadash head Ayman Odeh’s decision to break with decades of tradition by formally endorsing Benny Gantz for prime minister in 2019, he pointed to “those who began spreading the discourse of ‘influence.’” But he reserved stronger criticism for Ra’am’s Mansour Abbas: “He said he could only work inside the coalition. Now he’s in opposition — why isn’t he resigning?”

Ra’am did not respond to a request to be interviewed for this article; nor did the northern branch of the Islamic Movement, which split from Ra’am in the 1990s due to the movement’s opposition to participating in Knesset elections.

‘We can’t create a political vacuum’

Yet Abu Shehadeh is in no hurry to give up the Knesset. “Despite the game’s limitations, our society has benefited somewhat from parliamentary work.” Moreover, he added, “we can’t create a political vacuum and leave Palestinian society to be led by a group of Arabs from the Zionist parties [i.e. with no independent Palestinian parties present]. Such a vacuum will open the way for all opportunists.”

Abu Shehadeh also sees the Knesset as enhancing Palestinian citizens’ visibility in both the local and international arenas. “As an elected leadership, the opportunity to deliver our messages is greater.”

In that regard, the Balad leader believes that the war in Gaza and the international community’s renewed search for “solutions” have elevated his party’s core demand: transforming Israel into a state with full national and civic equality between Jews and Palestinians. “People are returning to discussions about the possibility of the two-state solution, which brings back Balad’s discourse about a state of all its citizens,” he said.

Tibi, of Hadash-Ta’al, also believes that despite all the challenges and restrictions, there is still room for action and influence within the Knesset.

“I, personally, and the Hadash-Ta’al list generally, are among the leaders of [advancing legislation] in parliament. Although we are working against all odds, we have succeeded in some issues,” he added, pointing to his party’s thus far successful efforts to obstruct the government’s planned budget cuts to Arab localities, which has not yet been approved by the Knesset’s Finance Committee.

For Khatib, the war in Gaza has strengthened the arguments of Abnaa el-Balad and other groups that support boycotting the Knesset — but he also concedes that it could end up increasing voter turnout among Palestinians.

Most read on +972

“People freaked out from Ben Gvir’s government and the extreme right,” he said. “This sense of fear and the fact that members of this government openly declare their racism will push more Palestinian citizens to participate in the next elections.

“But people have short memories. [Former Prime Minister Yair] Lapid and other politicians are no different from this government: they demand a deal [with Hamas] not to end the war or stop the massacres in Gaza but to bring back the hostages. The right-wing government is no different from other governments in Israel.”

A version of this article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.