The triumph of Kahanism and the impending return of Benjamin Netanyahu as prime minister have, quite rightly, dominated headlines in the wake of Israel’s dramatic general election last Tuesday. With a solid majority of 64 Knesset seats, Netanyahu’s right-wing bloc, which includes the extremist Religious Zionism slate led by Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben Gvir, is preparing to embark on an aggressive and radical program of action on both sides of the Green Line, with the incoming premier already receiving warm words of welcome from far-right and authoritarian leaders from India to Hungary to the United States.

On the other side of the political spectrum, an opposing development may prove to be just as pivotal — and no less dangerous. A few weeks before voters headed to the polls, the four Palestinian-led parties in Israel, which had been united under the “Joint List” just two years ago, affirmed that they would be running as three competing slates in this year’s election. Although they attained a combined total of 10 seats — the same as in the previous Knesset — with a 53 percent Arab voter turnout, these figures conceal a deep rupture that now exists between the parties and within the wider Palestinian community in Israel, the effects of which have destroyed a contentious yet vital engine of their politics.

The Islamist Ra’am, which was the first to split from the union in early 2021, has acquired five seats in the next Knesset, a bump up from its previous four. Hadash-Ta’al, a partnership between a communist and liberal party, has also secured five seats, albeit by the skin of its teeth after a last-ditch campaign to mobilize its base in the final days before the polls. The nationalist Balad, which was squeezed out of the remaining alliance with Hadash and Ta’al in September, has fallen just short of the threshold needed to enter the Knesset, despite an impressive campaign to rally votes on its own in less than two months.

The total disintegration of the Joint List, by cruel historical timing, is a critical piece of the far right’s momentous victory. As Kahanists prepare to seize various rudders of state power, Palestinian citizens (also referred to as ‘48 Palestinians) are finding themselves in an extremely vulnerable position, facing an emboldened ultra-nationalist camp that has put the question of non-Jews inside Israel — in particular, the Judaization of so-called “mixed” cities and regions like the Naqab/Negev — at the forefront of their agenda.

The targeting of Palestinians in Israel is nothing new; demographic warfare and racial domination have been core pillars of the state’s relationship with its “enemy citizens,” and during Netanyahu’s 12-year streak in power, the Knesset enacted dozens of new laws and policies curbing their rights even further. Yet there is no denying that the project of “internal colonization” has drastically intensified, not just in the dogmatic rhetoric of politicians and media pundits, but as violent facts on the ground. From settler militias on the streets of Lydd and Haifa to escalating home demolitions in unrecognized Bedouin villages, the rightward drift of Israeli-Jewish society has proven their colonial regime can become much worse.

Against these worsening threats, neither the Palestinian public nor its leaders appear to have a plan or the tools to resist what’s to come. The community’s politics, of course, are not confined to a handful of parliamentary seats, and the Knesset itself has long been a central foe to the fight for equality. Nonetheless, the re-fragmentation of the Arab parties is emblematic of the rapid erosion of Palestinian power in Israel and the loss of a political compass to guide their struggle, making the right’s ambitions for an even more brutal, tyrannical form of apartheid much easier to fulfill. How Palestinian citizens respond to this leadership crisis will be decisive not just for their own safety and welfare in this moment, but for the fate of Palestinians writ large.

A shattered consensus

The demise of the Joint List, while a long time coming, has been more consequential than many may have expected. Formed in early 2015, it was originally conceived as a procedural tool to help the small Arab parties cross a new electoral threshold (raised from 2 to 3.25 percent), which was intentionally designed to exclude them from parliament had they continued to run separately.

Despite the parties’ efforts to tame expectations, the List embodied a longstanding desire among the Palestinian public for their representatives to set aside ideological differences and advocate for their people’s needs as a united front. That hope brought Arab voter turnout to new levels over several elections; in 2013, the four separate parties earned a combined total of 11 seats; in the List’s first year, it won 13; by 2020, the number rose to a record 15.

The impact of the List’s six-year tenure was limited but noteworthy. As the third largest parliamentary bloc, the Arab parties acquired a new bargaining power vis-a-vis several government ministries and legislative committees, forcing officials to negotiate and accommodate some of their constituents’ socio-economic demands. The novelty of the union greatly boosted Palestinian citizens’ visibility from local media outlets to foreign government offices, asserting the community as a key player in the region. The List also distinguished itself as the central address for non-Zionist politics in the Knesset, demonstrating that the only true pro-equality and anti-occupation camp in the “Jewish state” was, in fact, led by Palestinians.

The List’s members, however, continually sowed the seeds of their own demise. Stressing that the List’s role was merely parliamentary, the politicians shied away from taking on a more assertive role in organizing the community beyond election seasons, insisting that the High Follow-Up Committee for Arab Citizens — an extra-parliamentary umbrella organization with no political power — was the real representative of the community.

As the List rose in prominence, personality clashes and ideological conflicts quickly dominated its decision-making, including over the role of its chairperson, held by Ayman Odeh. Petty grievances and partisan squabbles, such as how to “rotate” a representative in the 13th Knesset slot, festered in a public and embarrassing fashion. All this unfolded, of course, while its MKs (particularly the women members Haneen Zoabi, Heba Yazbak, and Aida Touma-Sleiman) faced the constant wrath of racist Israeli politicians, a demonizing media, and a largely hostile Jewish public which viewed them as troublemakers at best and “terrorists” at worst.

These fissures came to a head in late 2019 and early 2020 when the Joint List, in a controversial and divisive move, twice recommended former army chief Benny Gantz — who bragged about bombing Palestinians in Gaza “back to the Stone Age” — to replace Netanyahu as prime minister, hoping that he would forge a center-left coalition with Arab support. When Gantz dismissed the overtures in favor of a unity government with his rival, Palestinian citizens waited for their leaders to provide an alternative strategy — but the List had nothing else to offer.

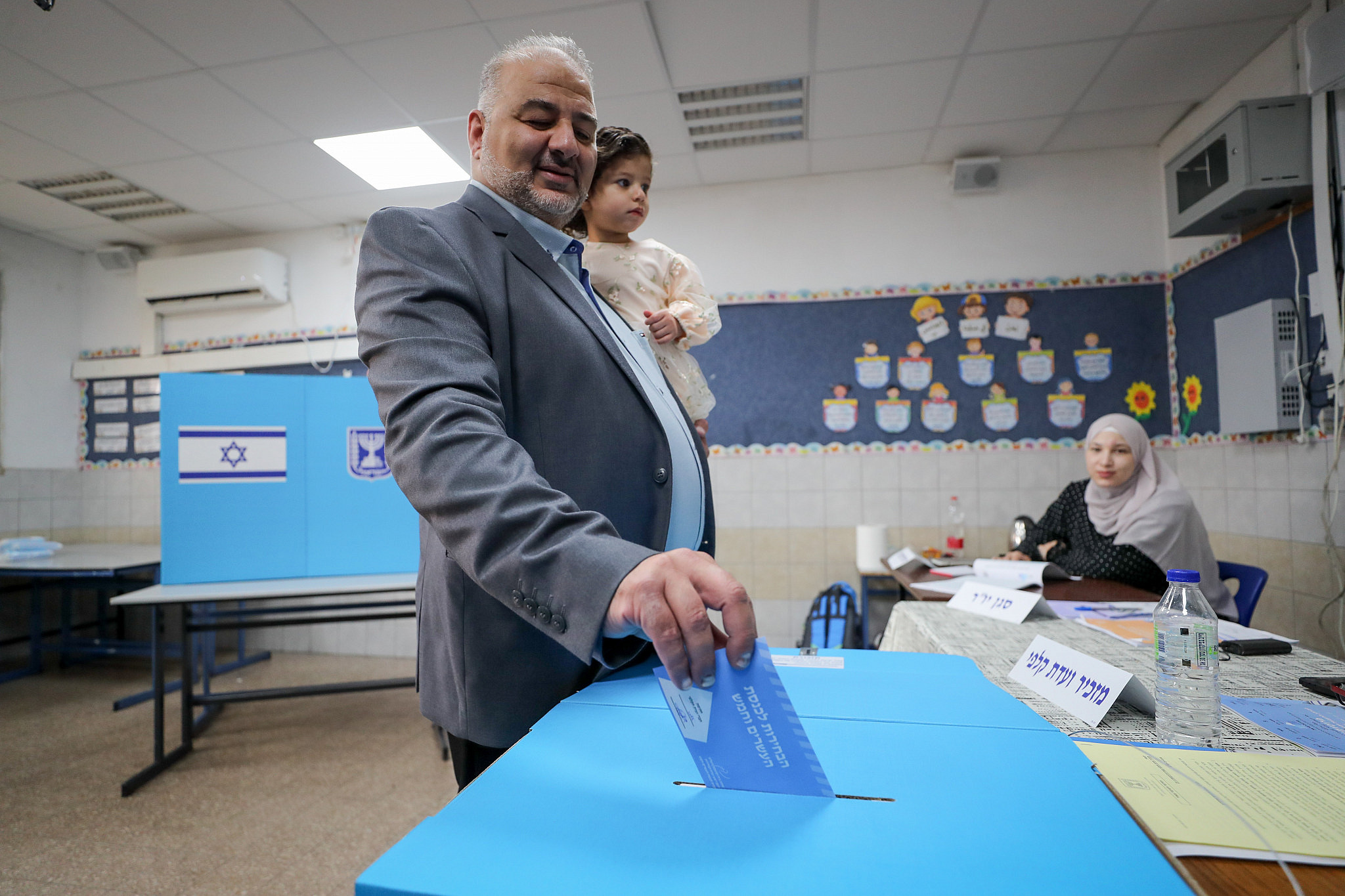

The following year, Ra’am head Mansour Abbas took the List’s approach to a new level, splitting from the other parties and offering to sit with any coalition regardless of its political stripes, including Netanyahu’s Likud. Abbas eventually became the final piece of the Bennett-Lapid “government of change,” a loose alliance of anti-Netanyahu parties that inevitably broke down after one tumultuous year in office.

Abbas’ decision to fully integrate into the Israeli political game was widely hailed as a “historic” moment. But the schism he created in the Palestinian community has left a devastating mark. In addition to peddling homophobic and anti-LGBTQ campaigns as a cudgel against the other parties, Ra’am deviated from an underlying consensus that has largely bound Arab politics in Israel since the Oslo Accords, which straddled a blurred line between pursuing civic equality as Israeli citizens while demanding freedom and statehood for Palestinians in the occupied territories. With the PLO’s consent, this entailed that any alliances with Israeli parties would be with the Zionist center-left, which in theory held onto some notions — albeit extremely skewed — of democratic values and a two-state solution.

Ra’am’s model of relegating “Palestinianness” for the sole pursuit of socio-economic gains shattered this consensus. But the party quickly learned that it could not abandon its Palestinianness so easily. When the Knesset tried to renew a law that bans Palestinian family unification inside Israel — a racist measure that directly affects many of Ra’am’s own constituents — the party was compelled to vote against its coalition partners. When Temple Mount activists escalated their entry into the Al-Aqsa compound in April, with Israeli police violently repressing Palestinians fighting the incursions, Ra’am temporarily froze its participation in Knesset activities to pressure the authorities to respect the holy site’s “status quo.”

Finally, when the government prepared to reinstate an emergency regulation that formally applies Israeli civil law to West Bank settlements, Ra’am’s members could not bring themselves to sign off on it; three of them abstained and left the Knesset floor as soon as they knew the law would pass without them, with one member voting against. (The same internal crisis afflicted Meretz’s Arab member, Ghaida Rinawie Zoabi, who also turned against her party and coalition over the law). These sagas, among others, forced Bennett and Lapid to admit their government could no longer function, leading them to dissolve it soon afterward. In a strange sense, Abbas’ belief that an Arab coalition partner could acquire leverage over the state actually worked — just not in the way he had intended.

The drift toward ‘Israelization’

Despite fierce public debate about Ra’am’s time in government, the party’s ideological conflicts do not appear to have dissuaded its supporters; on the contrary, Abbas’ integrationist approach has proven itself to be a mainstream ideology in the community.

In the April 2021 election, the party held a strong yet minority position, scraping four seats compared to the shrunken Joint List’s six. As of this week, the Islamist party stands equal to the more established Hadash-Ta’al, and having won several thousand more votes, even has the claim to being the most popular Arab party in the country. All this has developed in spite of the Bennett-Lapid government’s intensified policies against Palestinians in the occupied territories, including months-long incursions in the northern West Bank, a military offensive on Gaza, and continued forced displacement in East Jerusalem and Masafer Yatta. “Arab-Israeliness,” it seems, has found a viable political base once more.

A more critical version of this politics continues to be championed by Hadash-Ta’al, led by the Joint List’s former head Ayman Odeh and veteran politician Ahmad Tibi. Unchanged since the List’s collapse, the two parties insist that the only way forward for Palestinian citizens is to build a center-left alliance based on Arab-Jewish partnership and a commitment to end the occupation. But there are hardly any allies in the Knesset to even entertain this vision. Along with the rightward shift of the Israeli political spectrum, the Zionist left Labor party has been reduced to a mere four seats, while the slightly more leftist Meretz has failed to cross the threshold entirely. Lapid’s Yesh Atid and Gantz’s National Unity Party, by all accounts center-right factions, are also reluctant to rely on Arabs in any future coalition, deriding the Joint List as extremist while reeling from Ra’am’s conflicting allegiances in the coalition.

The fate of Balad, meanwhile, has been regarded as both a valiant and tragic story in this election. After clashing with Hadash-Ta’al over the List’s future strategy, which led Balad to be disowned from the union, Balad leader Sami Abu Shehadeh launched a remarkable campaign to get out the vote for his party, asserting itself as the unapologetic voice of Palestinian national identity and vowing not to sit with any Zionist coalition. Many former supporters, including young members who had grown disillusioned with the party over the years, returned to its aid and even boosted its base in many Arab localities.

The campaign, however, was still not enough to push Balad past the threshold, falling shy by several thousand votes. Despite Abu Shehadeh’s popularity, the party had long been weakened by internal ideological conflicts as well as relentless attacks from the Israeli establishment. After two decades in which Israeli politicians tried to expel Balad from the Knesset — denouncing its call for a “state of all its citizens” as an existential threat to the country’s Jewish character — it is a cruel twist of history that Arab leaders were ultimately the ones who enabled it to happen.

What does all this mean for the future of Palestinian politics in Israel? It is extremely difficult to say. Although Balad’s nationalist ideology closely emulates the spirit of the Unity Intifada of May 2021, which inspired and galvanized Palestinian citizens alongside their brethren under occupation and in exile, it is clear the party’s platform no longer carries electoral clout; in other words, most Palestinian voters see little benefit in putting Balad in the Knesset simply to act as a vocal bystander.

Rather, opinion polls repeatedly show that many believe having an Arab party in government is the best strategy for the community — not only to block the right-wing’s worsening policies, but to direct much-needed resources toward their urgent local needs, chief among them being concerns over gun violence, organized crime, housing, poverty, and unemployment.

This attitude is reflected in the equal footing of Ra’am and Hadash-Ta’al which, while different in significant ways, have still premised their strategies on adopting certain degrees of “Israelization” to advance the community’s interests. While Ra’am has taken this strategy much further, Hadash-Ta’al may find itself compelled to inch closer toward Ra’am’s direction too, as its constituents increasingly demand tangible results while coming to terms with the absence of a viable center-left bloc.

This trajectory is not inevitable: the fears over a low voter turnout on Election Day, which were also shared by Ra’am, is a reminder that the belief in the integrationist approach still hangs by a very thin thread. With Ra’am now kicked out of power by the incoming government — neither Religious Zionism nor many Likud members will ever agree to sit in a coalition with Arabs — that thread will likely get even thinner.

A broken national movement

Reeling from their humiliating defeat, the members of the anti-Netanyahu bloc have already begun pointing fingers at each other for losing thousands of votes through the cracks of their partisan competitions. Labor and Meretz (the former having rejected the latter’s call to run as a joint slate) are laying particular blame on Yesh Atid for swallowing their votes instead of encouraging a more collective campaign effort. So far, though, the Jewish politicians have said little about how the Arab parties’ division played a significant role in that loss — which is quite telling.

Neither the Zionist left nor right ever embraced the Joint List during its existence; aside from absorbing the vast majority of potential Arab votes, the union presented a discomforting challenge to Israeli parties’ claims of espousing democratic and liberal values. Many Jewish politicians still cannot fathom the idea of sitting in a coalition with Arabs, considering it political suicide, if not anathema, to their Zionist vision. Many more, however, simply cannot tolerate the Arab parties’ demands for full and unconditional equality; Jewish privilege, if not outright supremacy, has to be preserved. And if the Zionist parties did entertain the idea of partnership, it was only in the service of keeping Netanyahu out of power, a begrudging tool in an intra-Jewish political contest.

The Joint List’s breakdown and the far right’s surge is now likely to bolster the argument promoted by many Palestinians, especially those outside Israel, that the community should boycott the Knesset elections. A Zionist parliament, they argue, can never be a forum for defending Palestinian rights, and the Joint List’s inability to make significant gains despite being the third-largest slate is definitive proof of that. If the case for active boycott does not hold, disillusionment and apathy certainly will; with each passing election, Palestinian citizens have grown fatigued by their parties’ hollow words against an increasingly racist Jewish majority that makes it clear, every single day, that Arabs are unwanted.

What boycott advocates have not yet answered is what could fill the void beset by abandoning parliamentary representation. In theory, that is meant to be the role of the High Follow-Up Committee, which acts as a coordinating body between Arab parties (including those that don’t run for elections), municipalities, civil society groups, intellectuals, and other figures.

The committee, however, is neither democratically elected nor adequately representative; dominated by elderly and middle-aged men, the organization carries little authority beyond calling for general strikes (which often go unheeded) and was greatly outshone by the prominence of the Joint List. It didn’t matter that more Palestinian citizens knew the names of the elected Knesset members than of the appointed head of the Follow-Up Committee; traditional institutionalism won out over political evolution.

There are, of course, numerous groups and institutions that are organizing and elevating Palestinian citizens of Israel outside the parties. Grassroots collectives and local committees, many of them birthed or spurred by the Unity Intifada, are offering decentralized models of activism and communal support. Civil society organizations and professional networks, ranging from lawyers to psychologists, are providing crucial services amid a reality of state neglect and discrimination. Artists, writers, musicians, and thinkers are developing creative projects and spaces that are bolstering the community’s cultural influence. Arab municipalities are also coordinating, such as through the National Council for Arab Mayors, to lobby for their collective needs without relying on Knesset representatives.

These institutions are vital, yet they too suffer from a fundamental weakness. Despite Israel’s attempts to fragment them, the fate of Palestinian citizens remains intricately tied to that of the wider Palestinian national movement, which now finds itself gravely broken, disunited, and leaderless. Splintered by the Fatah-Hamas rift, the PLO’s demise, and the Palestinian Authority’s service to the occupation, the lack of direction for the liberation struggle is compelling many Palestinians in Israel to focus inward, with some resigning themselves to accepting economic rights in a discriminatory state instead of demanding political rights beyond it.

The Unity Intifada, led by a young generation of Palestinians who are more assertive of their national identity, showed there is a hunger for a more radical and holistic path to confronting the colonial regime under which they live. But without the means to translate this energy into real movement-building, these flashes of protest will inevitably be crushed and dissolved. A new political compass is needed to interlink the community’s disparate struggles, mediating their differences while still channeling them toward a common goal. Palestinian citizens have long been at the forefront of articulating such a vision, using their complex identities as a lens through which to reimagine a just and liberated future. They now need a concerted effort to help realize that vision — starting with accumulating the power to stop the Israeli far right from fulfilling its own.