Israel’s decades of violence toward Palestinians have had severe, accumulated effects on their mental wellbeing. The repetition of different forms of violence, from the Nakba to the present day, have inflicted different kinds of trauma on Palestinians, while also forging a strong sense of collectiveness that emerges organically during traumatizing periods.

That ongoing trauma peaked once more during May 2021, especially among Palestinians in the Gaza Strip who underwent yet another heavy bombardment by the Israeli army. But Palestinians living inside Israel, too, were exposed to lynching, police brutality, and a pervasive sense of danger as security forces abetted settler attacks. Taken together, these threats amounted to a combination of what psychologist Asrar Kayyal calls direct and “slow” violence, which, in its routine perpetration, inflicts “continuous trauma” on Palestinians.

“When several traumatizing events happen over a period of time, or a traumatic event keeps repeating itself — like an assault or a threat — it leads to complex trauma,” says Kayyal, whose family was originally from the depopulated Palestinian village of Al-Birwa, near Akka, and was internally displaced in 1948 to the northern town of Kufr Yasif. Continuous trauma, on the other hand, “is defined as a series of traumatic events which are still happening now and that are renewed all the time.”

With the outbreak of violence in May 2021, Kayyal knew that her and her colleagues’ services would be needed to meet the new wave of traumatization that would accompany it. And so, as events spiraled, she and other Palestinian psychologists from across the country put out a call for their peers, as well as social services, to volunteer to support victims, while also offering their own services to families in need of psychological support.

+972 Magazine spoke to Kayyal, who is also a children’s therapist, about her and her colleagues’ May 2021 efforts; the different kinds of trauma experienced by Palestinians over the decades and their cumulative impacts; and what meaning — and purpose — Palestinians draw from these histories. The interview has been translated from Arabic, and edited for length and clarity.

What was the psychological support initiative you created in May 2021, and what did it achieve?

It started at the very beginning of the events, and then grew to other areas [beyond Jerusalem]. Many lawyers volunteered to help, which was amazing. We started as a few psychologists; we put out an ad asking psychologists and social workers who would like to volunteer and families who would like to receive psychological support to reach out to us. In the first few days, the number of volunteers was a lot higher than the number of families. Everyone wanted to help.

When we had lots of volunteers and the number of detainees was on the rise, we divided ourselves between seven areas, each one matching the needs of the area: Haifa, Akka, Nazareth, Jerusalem, Lydd and Ramla, the Naqab, and Umm Al-Fahem.

Palestinians from the north used to come to Al-Aqsa to support the people of Jerusalem, which led to many of them getting lost [in the chaos when police raided] or being arrested. Jerusalemites are used to the idea of arrest, so they are practiced in dealing with it — you will never see a Jerusalem mother in front of the detention center [where her child is being held] not knowing what to do, because the repeated arrests have created a social mechanism [for handling the fallout]. Although it is always scary, mothers will need psychological support.

What happened in May in Jerusalem was that parents from the north would wait outside the interrogation center when their sons and daughters were arrested. So we saw interrogators turn minors who took to the streets to practice a basic human right in calling for freedom, or who were praying, into terrorists, and then blame the parents for it. These parents came out of the interrogation center distressed and panicked after being told that their son’s future is over, that the Israelis have marked him, and that they [the parents] were in this alone.

We dealt with families who saw a glimpse of their son as the army attacked Al-Aqsa, before tear gas was fired, people were injured and arrested, and the soldiers closed the mosque door, trapping people inside. We saw a lot of severe panic attacks, [including among] kids who got separated from their parents and could not emotionally regulate themselves because of their young age.

Our presence made a difference for the parents, and to what they reflected to their son who was being interrogated. We comforted and supported them, and they in turn comforted their children when they came out of the detention center, instead of stressing out and believing that their son’s future was over, or blaming themselves and their kids.

We also had in mind the psychological needs of those who were put under house arrest, because parents can sometimes unconsciously do the job of the jailer when their house has turned into a jail — ordering their child not to write anything [on social media], not to leave the house, not to express themselves, not to do certain things. Families’ experiences with arrests and especially house arrests are so brutal that they do not want it to be repeated.

The volunteer psychologists started giving out our phone numbers to families for support if needed. Families called when they had questions regarding behaviors they found difficult to understand or deal with. We also provided psychological first aid for dozens of mothers who were not allowed to speak to their sons, as the Israeli court kept extending their detention week after week.

Lawyers would also call us, distressed by the amount of violence they witnessed against the detainees; they saw minors and young men beaten so badly. We [also] saw savage beatings of kids in Jerusalem, it was unreal. In Nazareth, the detainees kept shaking after their release because of the violence inflicted on them. In Haifa, minors started vomiting outside the detention center because of severe panic attacks, due to the beating they experienced which caused their heart rate and their breathing to spike.

It was very important for us to keep the privacy of the families — we did not want to expose them to [their details] being used by anyone. We were afraid that someone would call a mother with a son in detention and extract information from her about his case, so we depended on the lawyers to connect us to families in need of psychological support.

What is the difference between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and Palestinians’ continual re-traumatization?

PTSD is when a traumatic event takes place and ends but our reaction to it accompanies us for a long time after the event is over. When several traumatizing events happen over a period of time, or a traumatic event keeps repeating itself — like an assault or a threat — it leads to complex trauma. The other kind of trauma is continuous trauma, to which science has more than one approach, and it is defined as a series of traumatic events which are still happening now and that are renewed all the time.

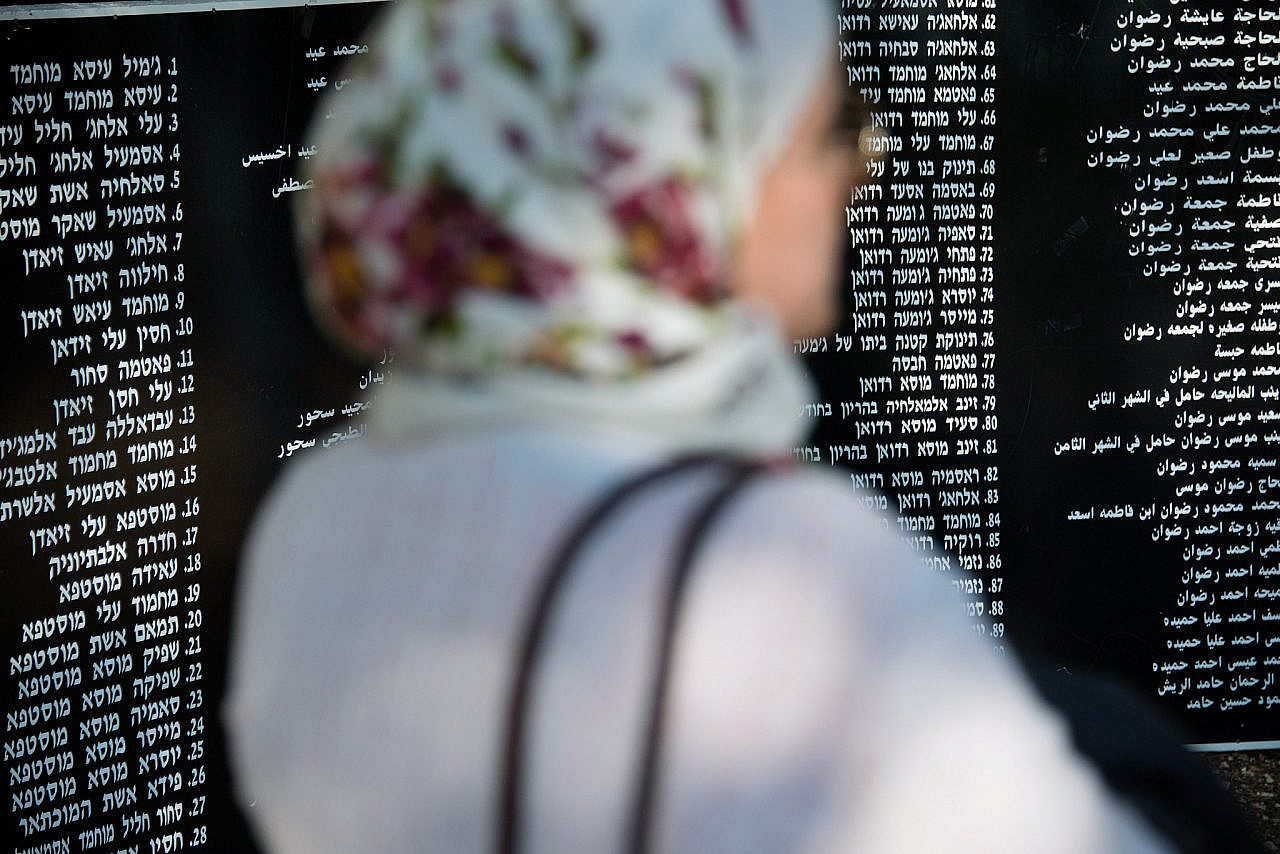

In our case, the Nakba was not one big event that took place and ended. Before it, there were revolutions. During it, there were attacks, shellings, land confiscations, and terrorization that continue today. After the Nakba, the Israelis enforced military rule for [over 18] years, and there were several massacres, for example the [1956] Kufr Qasem massacre. Some villages were not occupied in 1948, but Israel finished the job in the coming years until 1952. Then there was Land Day in 1976, the Intifadas, May 2021, and this year, when Bedouin citizens in the Naqab/Negev struggled against the expropriation of their land, and against the afforestation project of the Jewish National Fund at the expense of unrecognized villages.

This is only if we are talking about Israel’s direct violence, which includes shooting, beating, massacres, and so on. But there are other elements that may contribute to the continuous trauma: “slow” violence, or symbolic violence. Being deprived of resources and daily racism are slow violence, while symbolic violence is expressed in the control of the narrative, control of the symbols, what we study, and what we can express and what we cannot.

During the years of military rule [inside the Green Line, from 1948 until 1966], for example, soldiers forbade us from moving from one place to another. [Today,] some of us are under siege, others are behind a wall, some of us are living in refugee camps, and some of us are in overcrowded cities and villages trapped between settlements, prevented from experiencing our collective selves. Institutions that do not represent you, educational curricula that forbid you from expressing yourself, and tell you a story that is different from your story — all of this is called relegation and deprivation of self-expression and resources, which is symbolic and slow violence.

All of these kinds of traumas hinder Palestinians from normal self-achievement because they are oppressed in many ways. It does not have to be that they were beaten during the Nakba, for example, or that they witnessed the killing of a close family member, as my dad experienced, or witnessed massacres. It is the accumulation of years in which Israel strips the rights of any Palestinian who tries to resist oppression or express their Palestinian identity.

I can give a personal example here: my mom and others of her age who lived during Israel’s military rule are, to this day, scared of even saying the word “Palestine.” When my mom was a little girl the Israelis chased her uncle, who was a leftist political activist, beat him, and jailed him for speaking out about Palestine. She remembers that the army raided their house at night looking for her uncle. They removed the blankets from the kids while they slept. They went into the chicken coop and killed some of the chickens, which is an incident that scarred her deeply. She did not speak about it openly, I had to ask her repeatedly and she slowly opened up.

I remember when I left for college she advised me not to talk politics. She was living in fear and denial of Palestine, she wanted us to assimilate silently into the state. Her fear today is related to the event of the army raiding her home — it is PTSD. There was continuous horror and terror during the military rule period, where Palestinians were stripped of their freedom of movement, farming, and self-expression, which caused prolonged or continuous trauma. This can also be linked to intergenerational trauma since her parents were refugees that underwent and experienced traumatic events.

What does it mean to have generational trauma?

Palestinian scholar Adnan Abu El-Hija, in his study on how trauma is transferred from the generation who lived through the Nakba to future generations, found clear effects on the second generation that had not witnessed the horrors of the Nakba. In families that did not discuss the Nakba, [and] in which fear went unaddressed, the second generation suffered from a negative grasp of the world, felt that dreams cannot be achieved, had an angry approach to dealing with things, and had different physical pain that had no medical explanation. The families who spoke about the Nakba were able to liberate themselves from these symptoms.

After the trauma of the Nakba, a whole nation — or at least Palestinians living in the land occupied in 1948, because Palestinians in the land occupied in 1967 were still able to fight back and express their political opinions — lived under military rule for [almost] 19 years. A whole generation was born and raised while being prevented from expressing themselves, and [who] couldn’t even say they were Palestinians.

This did not stop with the end of military rule: it continued through Israelized educational syllabuses. Israeli archival [materials] show clearly how Israel wanted Palestinians to study science majors more than humanitarian subjects like philosophy, psychology, and sociology — which they achieved by controlling the quality of teachers in schools, and through the interference of the intelligence services in who gets to teach in schools and who doesn’t.

Then the Nakba law [was passed] in 2011, under which any publicly-funded institutions that commemorate the Nakba can be punished [by having that funding withdrawn]. The silencing continues. If we think about Abu El-Hija’s study on how horrible the effects are for families that did not talk about the Nakba, imagine a whole community being silenced. We are forced to learn about Jewish history, which is a good thing, while we are forbidden from learning about our Palestinian history or commemorating the Nakba, or talking about our trauma, our loss, or anything that we have been through.

Another difference between classic trauma and the trauma we experience in Palestine is that our trauma has meaning for us in our collective consciousness, because we struggle together to survive. It has deep meaning to us as a nation.

In the settler-colonial substitutional context, the state is built on the land of the colonized nation and aims to erase them. Our struggle against this ethnic cleansing has meaning for us, and the weight of the traumas is handled better if people practice their own collective identity. We are trying to preserve our collectiveness in the face of attempts to erase it. But if Palestinians were to go through trauma without unity, dealing with its effects would become harder because it would lose meaning, as Viktor Frankl said.

How do the effects of trauma differ when it comes to children as opposed to adults?

As adults, we have more capacity to deal with difficulties. Generally, a child does not have enough adaptation mechanisms and emotional experience with hardship. As we get older, we develop mechanisms to deal with emotional challenges in different circumstances. What we can handle as adults, we cannot handle as children.

As an adult I know, for example, that during an interrogation the interrogator can tell a lie, but a child cannot comprehend that. A technique that Israel uses a lot in interrogating kids — which in itself causes trauma — is to tell the child that they did something and that they have photos of them doing it. The child starts doubting their reality because they are in front of an adult who is an official representing the state and therefore must be right. The kid then starts to think, ‘I might be wrong.’

Let’s go back to last May, and all the attacks and killing that took place. If children are prepared for [this kind of event] by knowing the symbolism of it rather than viewing it as an isolated event stripped of its political and historical aspects, it would help them to process the events emotionally. But if these events are not spoken about at home, it will deepen the kids’ sense that the world is an arbitrary, out-of-control, and treacherous place, which heightens their fears. We are not helping children to build a clear story to adjust to new traumas, because when they can give them meaning, they will have an easier time overcoming them.

When there is a colonizing power that seeks to eliminate as many of the colonized as possible and take as much as possible of their resources, the natural humane response, historically, was to resist it. If [your rights] are violated, it is only normal to become angry and try to protect who you are. When the system tries to explain that situation to you differently, that is the major difference between kids and adults.

What are the differences between the effects of trauma on Palestinians during the Nakba, the first and second Intifadas, and the events of last May?

The Nakba, despite being [the latest in] a sequence of regimes under which the Arabs were living, like the Ottoman Empire and the British Mandate, was shocking and traumatizing. The settlers immigrated to Palestine slowly and the general view was that they were poor and refugees here. Many Palestinian villages hosted them, because they never imagined that they would take over their land. Imagine a Palestinian farmer who has been living on the land his ancestors owned for hundreds of years, and has developed a deep relationship with that land — it would be unimaginable for him to lose it.

There were also many horrifying massacres during the Nakba, and a lot of them remain unheard of. I know the story of Al-Birwa because it is my [displaced] village. They would kill several people in front of their relatives and then open the northern border for people to flee to Lebanon; they would even have trucks to haul them. They killed and abused some to scare the rest.

The trauma of witnessing these acts of violence and killing takes a long time to process. Humans first enter a state of denial, which is why many Palestinians took their house keys with them and were sure they would come back. This is a natural human response. Palestinians were then forced to stay silent during the military rule, which messed up the stages of dealing with loss and made it harder to reconcile, leading to retrogression, sadness, and depression. They realized they were much weaker than the [Israeli] state, and that they could not reconquest what was theirs — and their whole world collapsed.

In 1967, the Palestinians were convinced that Arab countries could help them, but that failed, and people started believing they were in a deadlock with no way out. Everyone felt a sense of helplessness that [nonetheless] had to be swallowed if Palestinians wanted to live in what had become Israel. In critical psychology, this process is called “introspection of helplessness,” as the psychoanalyst Mustafa Hijazi has named it, or “internalizing defeat,” as Dr. Ibrahim Makkawi called it.

At some point, Palestinians realized they have agency, which is what makes the Nakba different from the Intifadas and May 2021. What is similar about these events is how they did not stop at geographical borders or separation — they didn’t prevent them from expressing themselves as a whole and practicing their identity. Palestinians complete each other. When a nation is divided and cut off from its different parts, it develops learned helplessness where they collectively internalize that they are powerless.

The first Intifada achieved gains, which is why the second Intifada followed it. On the other hand, the colonizing power tries to make Palestinians pay a high price for their resistance, which is why Israel followed, for example, [Yitzhak Rabin’s] “bone-breaking” policy, signed the Oslo accords, built the apartheid wall, enacted the siege. All of this is to prevent Palestinians from rising again — it is how a brutal colonizer acts. It is savage because it does not see the colonized as human beings.

What happened in May 2021 restored to Palestinians the ability to look at the big losses they experienced in all of the previous times, and made people realize that they do not want to be forced into silence like after the Nakba. The grandchildren of those who experienced the Nakba, and who were able to learn a lot of new mechanisms [to deal with trauma] on a personal and societal level, can copy those abilities and translate them into collective action.

One such event that took place during May [2021] was when, during Ramadan, police stopped buses full of Palestinians from Lydd who were on their way to pray in Al-Aqsa Mosque. People felt overpowered and helpless at being prevented from practicing their right to worship and their Palestinian wholeness; Jerusalem became the city that cannot be reached. But Palestinians from Jerusalem decided to pick them up in dozens of cars, and people from the north joined in. Everyone was given a ride. Palestinians found themselves able to achieve their goal when the Palestinians in Jerusalem “completed” the Palestinians from Lydd in the face of the cruel system which acts arbitrarily. After this incident, Palestinians stopped feeling powerless for a while.

When they saw this level of capability, some cities and villages which have not shown any political expression or resistance in the last 70 years started to protest, and expressed themselves despite the fear. That is what happened in May and continued to happen throughout last year. In December and January, the people of the Naqab continued to resist the attempts to confiscate their land. The Palestinians in Jerusalem were empowered by Palestinians [inside the Green Line], and Palestinian Israelis were empowered by the Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. The Palestinian collectiveness was completed by uniting its shards.