Any comprehensive discussion of the nature of the Zionist project in Palestine and the ongoing Nakba must address the ways in which, from the very beginning, power relations between Ashkenazim (Jews of European descent) and Mizrahim (Jews native to the Middle East) have affected and been affected by the dispossession of the Palestinian people. The roots of Israeli colonialism lie in the European origins of Zionist ideology, and it is these same origins that also produced structural discrimination against Mizrahi Jews within Israeli society.

As such, in order to take responsibility for the Nakba, redress the injustice, and build an equitable society, we must ask: what responsibility do Mizrahim bear for the Nakba? Have they played a uniquely significant role in uprooting the Palestinian people? And can they play a uniquely significant role in promoting justice and redress?

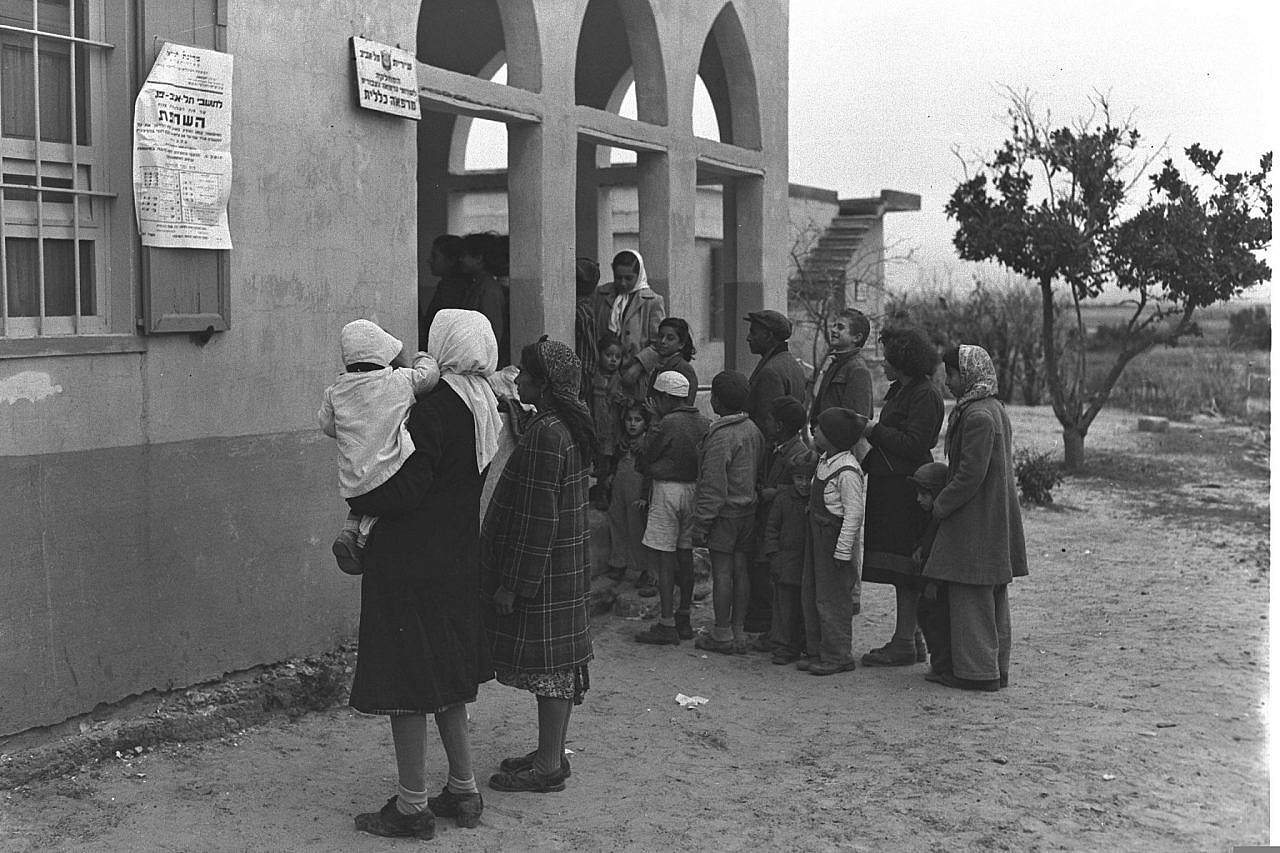

In the Tel Aviv-Jaffa area, the pattern of the Mizrahi role in the Nakba is easily identifiable. After the occupation and depopulation of Palestinian localities, the lands and homes were transferred to Israel’s Custodian of Absentee Property, established by a law in 1950, which used them to house Jews; many of them were Mizrahi immigrants, but also refugees from battle zones during the war. This populating of “abandoned” property formed part of a deliberate strategy to prevent the return of Palestinian refugees.

The property rights of these new Jewish inhabitants, however, were intentionally left unregulated. Today, many of the Jewish residents are considered “squatters,” and the state evicts them without appropriate compensation, usually to make room for high-end housing projects. Thus, under the legal guise of the Absentee Property Law, the agents of Palestinian dispossession and erasure become the secondary victims of the same ideological project.

The story of the depopulated Palestinian village of Salama in southeastern Tel Aviv — now known by the Hebraized name Kfar Shalem — illustrates how this mechanism continues to operate to this day. Just as in Jaffa, Al-Jammasin al-Gharbi (Givat Amal), Abu Kabir, Summayl, Al-Sheikh Muwannis, and the other “neighborhoods” that used to be Palestinian communities, the State of Israel and the Tel Aviv Municipality extract profits from the assets of Jewish residents who are not even the original owners, adding further insult to injury.

Since the 1960s, the Israeli authorities have sought to evict Salama/Kfar Shalem’s Mizrahi inhabitants, who in turn have fought a long but largely unsuccessful struggle to remain in their homes. One resident, Shimon Yehoshua, was shot dead by police in 1982 while trying to prevent the demolition of his house. Subsequent eviction waves have displaced hundreds of former residents, most recently to make way for the construction of the Tel Aviv light rail. Together with the erasure of the last remains of Palestinian existence in Salama, these evictions expose the ethno-capitalist machinations of Zionism.

We interviewed three Israeli Jews who grew up in Kfar Shalem in order to elucidate this process, and to explore the implications of dividing the loot of the Nakba along ethnic and socioeconomic lines.

‘Instability is built into our experience’

Longtime educator and social activist Pazit Adani was born in 1977 in the Yedidia neighborhood, on the lands of Salama. Her family first arrived in Jaffa in 1945 as part of a group of 450 Habbani Jews from Yemen, organized by her father’s second cousin Zecharia Adani. After spending some time in transit camps (ma’abarot), and following the occupation of the Palestinian villages in 1948, members of the Habbani community were settled on the eastern lands of Salama (today, Ramat Hen and the Ramat Gan National Park) and in Moshav Bareket, founded on the ruins of the Palestinian village of Tira in the Ramla Governorate.

As part of the planning of the National Park in the 1950s, members of the Habbani community who lived east of the village were relocated to the southern lands of Salama,, in what is now Yedidia. In December 1949, the municipality newsletter reported that the neighborhood contained “40 to 50 homes” (which probably belonged to the Palestinian farmers of Salama), and was “home to some 250 families (20 of which are Ashkenazi, and the remainder Yemenite immigrants).” In a map produced by the Labor Ministry’s Survey Department in 1959, the area is marked as a transit camp. “Our house was very small,” recalls Adani. “It was located on a well that became sewage because there was no infrastructure in the neighborhood.”

Like other areas where the state settled Jewish families in Palestinian properties, the Yedidia neighborhood was neglected by the Israeli authorities. In 1949, it was reported: “There is no road, and the neighborhood is also neglected in terms of sanitation. There is a water pipe network, but there is no water; there are wells, but no electric pumps. Water is brought in cans from Salama. Due to the water shortage, the [agricultural] labor of the neighborhood’s inhabitants goes to waste … There is no school or kindergarten in the neighborhood.”

Since then, and to this day, says Adani, members of the Habbani community have sent hundreds of letters to the authorities, repeatedly asking to regulate land ownership and provide solutions for the inhabitants. Until the early 2000s, the neighborhood was considered “a municipally undefined area,” and although it was officially annexed to Tel Aviv in 2001, Yedidia still suffers from neglect and infrastructural problems.

Adani describes how, at a very early age, she and her friends in the neighborhood realized the huge disparity between them and their Tel Avivian peers. Her grandfather worked in the municipal sanitation department, which removed garbage all over the city; in the Yedidia neighborhood, due to the lack of sanitary services, he had to burn the garbage once a week.

“We have no street [name], we have no number, we’re not on the map,” says Adani. “I can’t explain where I live. Ever since I can remember, eviction orders have been hovering over the entire neighborhood.

“It’s a disadvantaged community by definition, a community subjected to eviction orders,” she continues. “Instability is built into our experience. Since real estate is not regulated, we are still fighting for our house.” This situation “affects every move,” and “each time it weakens the community a little more.”

Adani describes the neighborhood today, dipped in lush greenery, from an ambivalently romantic perspective — one that yearns for the wide spaces of childhood. But she is also aware of the lives that were here prior to 1948. She says that the neighborhood’s inhabitants used to call the different parts of the city by their Arabic names, like Salama, Al-Manshiyya, etc; only when she was 15 did she realize that the names were of the Palestinian communities.

‘I kept wondering who lived in this house’

Ayala Springer was born in 1950 and came to Salama with her family at the age of 4. Her parents and uncles had previously been living in the homes of Palestinian refugees in Al-Sheikh Muwannis (on whose lands Tel Aviv University would later be constructed), despite the fact that they were not new arrivals; her mother’s parents lived in Kerem HaTeimanim, Tel Aviv’s Yemenite neighborhood, and her father’s parents lived in the Yemenite neighborhood in Silwan, Jerusalem.

Springer and her parents lived in Salama, which they called “the village,” for about a decade. She waxes nostalgic as she describes life there: “Take it from me, I’m willing to go back there tomorrow.”

The family lived in two homes, both of which were “homes of Arabs who were expelled.” The first home “had these big doors [in the style] of the Arabs,” Springer recalls. “We had a big iron key, like they show in the movies, for palaces. Who had a key? The doors were open. What was there to steal? Everyone [was] on the same level, everyone had the same things. All doors opened onto the inner courtyard.”

She remembers the warm relationships between immigrant families from various countries: “Everyone spoke Hebrew, and those who didn’t know Hebrew, Arabic … We were like siblings, one family. No matter what it was, we would love and help one another. Sometimes we forget they changed [the name] to Kfar Shalem. It was a village: everyone knew everyone, and helped everyone.”

Springer describes the old village as a main street with a central square, around which were a restaurant (“Madmon’s”), grocery stores (“Menachem’s” and “Gindi’s”), and other venues (a fishmonger, a dry goods store, and the post office). The houses were on the small streets across the main road.

“But today, it’s unrecognizable,” she says. “You go there [and] say, ‘Was this where we used to live? No. Maybe here?’ The place is already full of high-rises, and all the [bare] hills that used to be here are gone. It was all orchards, and they built buildings.”

The pleasant childhood memories do not compensate for her sense of being exploited. The state settled Springer’s family in the houses of Salama’s Palestinian refugees and neglected the village, until it became worthwhile to cash in on its profits by selling the land to developers. “All these old-timers, the first [Jewish residents], were good people, [but] naïve,” she says. “So [the authorities] told them, ‘Come here, we’ll give you a house,’ and built high-rises on their land, which they sold and made tons of money. It’s really a pity — it used to be a beautiful, warm, loving village.”

Regarding Salama’s Palestinian history, Springer says that they “didn’t know who lived in the houses, but we knew that the Arabs escaped or were expelled. I kept wondering who lived in this house, where they went, with kids, poor kids.

“My aunt’s house in Al-Sheikh Muwannis [also] used to be an Arab’s house, with those large and heavy doors with those keys,” she continues. “What about the people who used to be here? It doesn’t seem like it’s only a dad, a mom, a boy and a girl [who lived there]; it looks like also a grandpa, grandma, [the whole] family.”

And if Israel hadn’t expelled anyone and people simply tried to live together in the village, as Arabs and Jews? “Believe me, it would have been great,” says Springer.

‘It was kind of extraterritorial’

Effi Banay was born in Salama in 1971, in buildings erected in 1967 not far from the village center, where Jewish immigrants — mainly from Morocco and Iran — were housed. “They brought all the people from the airplane to Salama,” he says, “and my mother was neighbors with her former neighbor in Isfahan.” According to Banay, most Iranian Jews did not want to immigrate to Israel, and the Jewish Agency went to great lengths to encourage them to do so, including by producing propaganda films.

“They used to come and screen those films in the children’s schools [in Iran],” says Banay. “My uncle, my mother’s brother, saw such a film, came home [and] told my grandpa, ‘I want to join the army.’ Because what did they show him about the army? Women soldiers, oranges, and the beach. So he said, ‘Gosh, I want to go there and meet a girl’ — [it looked like] a much more secular world.”

Banay’s uncle thus “went to Israel and then my grandma freaked out.” She took her entire family and immigrated.” Banay says that if you were to ask most of these people today whether they would have made the same decision if given the chance again, they would not have immigrated to Israel.

In the Salama of his childhood, Banay describes a segregationist social fabric, made up of separate communities of origin. He would speak Persian at home, with the neighbor, at the grocery store, at the synagogue, and with his grandma. “Until I was four, I didn’t know Hebrew,” he recalls. “I went to the kindergarten, [and] I learned Hebrew there.”

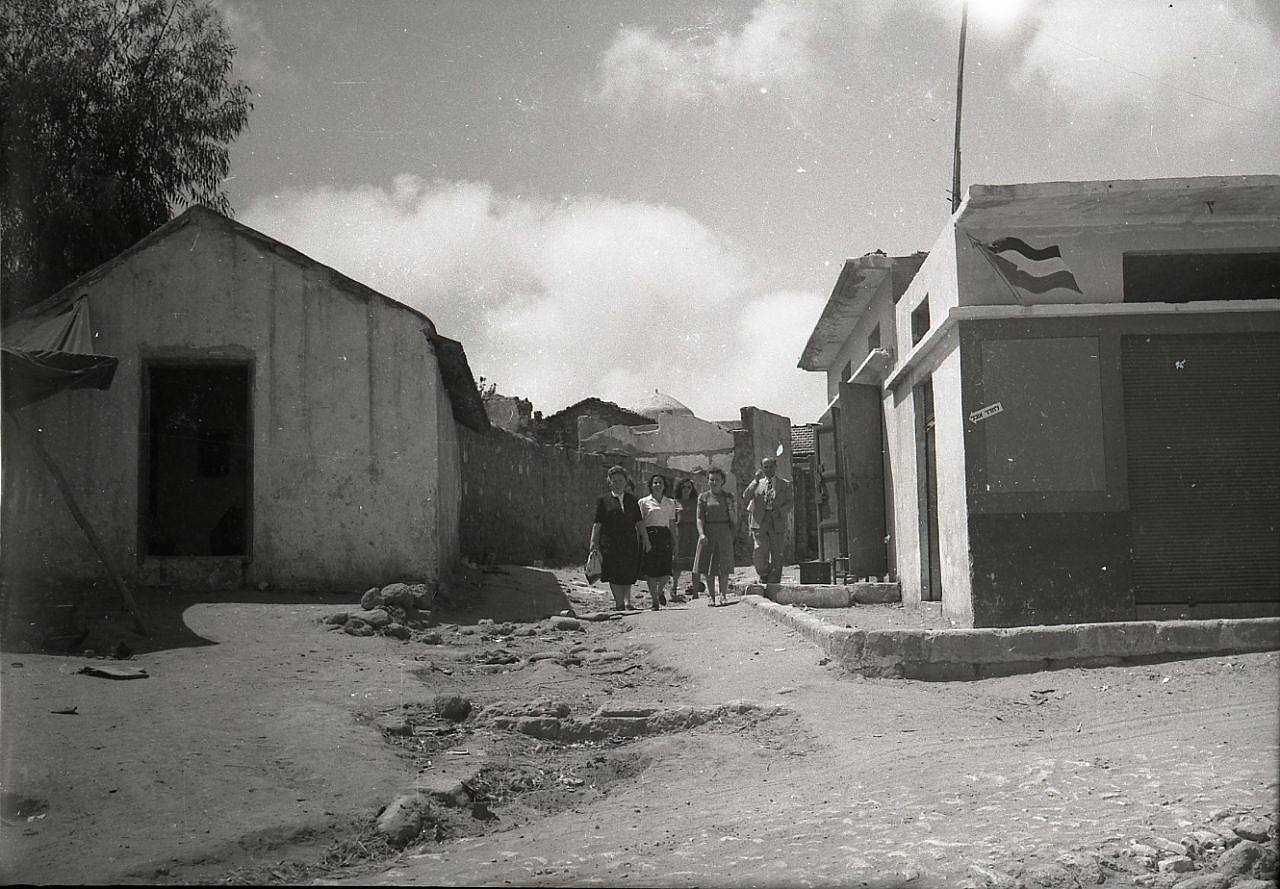

Even after buildings were constructed further out, the center of what had been Palestinian Salama remained the neighborhood hub. That is where the stores used to be, and where the children of Kfar Shalem used to play in the afternoons. In Banay’s childhood years, it was a “territory of chaos.” The village center was “less orderly, less clean, everything [was] broken [and] destroyed. The idea was that’s where you go to run wild, to cut loose.” In the village center there was a mosque: “You could sneak in, go up on the roof, [and] play around.”

He clearly remembers the difference between the way the municipality treated the village center and the new neighborhoods. “In my area, you couldn’t build treehouses because the municipality kept destroying them; over there, you could build a house on the tree, and it would stay there for months.”

But there were uglier sides to the neighborhood, even from a little boy’s perspective. “It was like a jungle,” says Banay. “I remember, for example, how they used to abandon cars there — steal a car and tear it apart, and leave the skeleton there. [They would] steal a cow or a sheep from a flock, butcher it, [and] take everything — all the bones remain behind.” Garbage from factories was also dumped there; “it was kind of extraterritorial.”

Paradoxically, the Tel Aviv Municipality’s deliberate neglect, originally designed to slowly erase Palestinian existence from space, made it all the more apparent. “The municipality did nothing,” Banay continues. “[They] didn’t clean, there were no sidewalks, no paved roads. There were these abandoned shacks that you didn’t know whom they belonged to, there were still orchards left. Everything looked like somebody left it and went away.”

Eventually, he says, the municipality would come and demolish these remains, but this only revealed more of Salama’s Palestinian past. “We would come the day after and suddenly discover that there was a well next to the house, which until now we didn’t notice,” Banay remembers. “Sometimes, the original structure of the house that used to be on top of it [was visible], and the [well’s] pump.”

But as a child, Banay didn’t know what all this meant. “We thought, ‘Oh well, this was before we were born.’ Today I know that it was from an earlier period of the village.”

‘We would come back from school, riots would start’

Until a community center was built in the neighborhood in the 1980s, the Salama Mosque was used as a youth club and a meeting place. “Inside, there’s the alcove facing Mecca, there’s the stone podium, and there are rooms you can enter,” Banay recalls. “And upstairs there’s a staircase leading to some room on the roof that’s very beautiful. The scenery is amazing because it’s built at the highest spot in the village.”

As a child, Banay remembers asking why the mosque was there. “People said: ‘There used to be Arabs here, there was a war, they fled — simple. Like 1-2-3. And there was a legend about a treasure hidden in the tomb.”

When the community center was built, the Tel Aviv Municipality sealed the mosque and began evicting the residents of the buildings next to it, in order to leave the mosque in the middle of a large park. The gradual demolition of Salama’s original residential buildings only made the mosque look more foreign in the Judaized space.

“People were highly ambivalent about this building,” says Banay. “Nobody said ‘Let’s destroy it,’ [but] it didn’t represent anything religious to them. It became a building that you’re used to seeing in the middle of the village, because all of the nearby houses were very similar to it.

“Today, because the nature of the [new] construction is highly modern, it looks even less relevant to the area,” he continues. “The population is also changing: people from a different socioeconomic class are moving there, and they’re not used to seeing a mosque right next to their house — it looks weird to them. Mizrahi Jews came from a place where it was normal [to see] a mosque near your house, [but] people from other ethnic communities or other areas find it very odd.”

By the 1980s, real estate prices began to soar, and the municipality changed its policy. “When the land started becoming a little more expensive, the evictions began,” Banay explains. “There was the story of the Yehoshua family: they came to evict them and they shot [Shimon].

“There were several waves of riots. Every day, we would come back from school, riots would start, and we would burn tires and block roads,” he continues. “People there felt that the system was against them, that they were being neglected, and that they were the last in the order of priorities.”

When asked if the people of Kfar Shalem were opposed to the destruction and erasure of Palestinian Salama, Banay says no. The struggle was against the evacuation of the people of Kfar Shalem without compensation; they did not speak about their complicity in the ongoing Nakba, at least not explicitly. “Look, the people there were also busy making a living,” says Banay. “These are people who go to work, come back home, and they don’t have spare time for [other] agendas — they want to survive, survive, survive.”

Shared longing

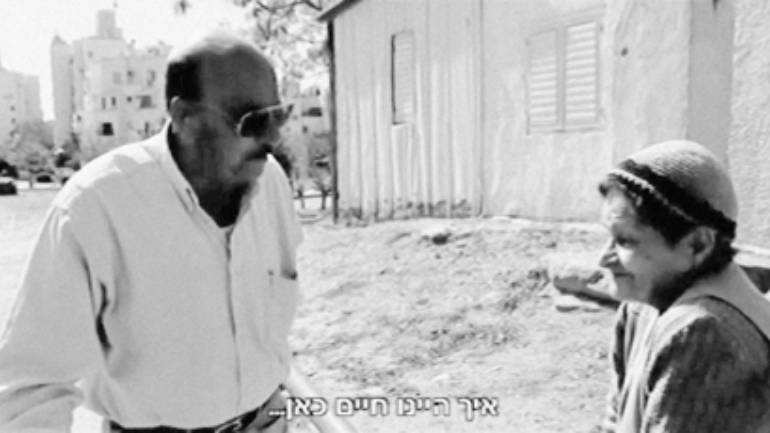

In 2010, Banay released a documentary film titled “Longing,” in which he returns to his childhood neighborhood after having moved to central Tel Aviv. Banay tries to decipher the Salama story: Who were the village’s original Palestinian inhabitants? How did the Jews who took their place feel about it? How did the Jewish inhabitants’ struggle against their own eviction develop?

The film is named for the longing that Banay’s mother felt to return to her childhood home in Isfahan in Iran. But in choosing to direct a film about Salama, Banay wanted to explore his own sense of longing. “When I moved [to central Tel Aviv], I used to come and visit [Salama] every once in a while,” he says. “I’d walk around there, visit the neighborhoods, never realizing why I was attracted to the mosque.

“I began recalling my mom, who used to tell me what it’s like to relocate, and how she misses her home,” he continues. “And I said, gee, I understand her; I moved four kilometers to another [house] in a better area — if I feel that longing, she must have felt it a thousand times stronger. My empathy intensified when I went through it myself.”

Banay was exposed to the longing of Salama’s Palestinian refugees in the course of making the film, when he heard stories about their visits to the village after the 1967 occupation, which enabled some Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza to visit what was then Israel. “One would take a bus from Ramallah in the morning, arrive at Kfar Shalem, knock on the door of the house where he used to live and say, ‘Can I see my house?’ And people would let them in.”

Abu Sami Mas’oud, a Palestinian refugee from Salama, recounts in the film that from time to time, he travels to Salama on a Friday, with a folding chair, and simply sits next to the mosque. “I come back fresh,” he says. “It’s the feeling. The feeling of the land, the feeling of where you used to live, and you remember the good things. There was no war, there was nothing. Everything was good and beautiful, peaceful, calm.”

Banay emphasized that there was never any resentment or fear toward Mas’oud, but only hospitality and a sense of a shared tragic destiny. “People here support the Likud [rightwing party] — they’re no leftists, it’s not Meretz. [But] they let him in, they offered coffee, he showed them where he used to live. Thank you, goodbye, and back home.” He says that “the sympathy was very natural,” given that many of the Jews who were settled in Salama had also left their original homelands in Iraq, Egypt, or Libya.

Among the stories of visiting Palestinians, Banay kept hearing about refugees who asked to enter a house or a well, then removed a brick and took out gold that had been hidden there before the Nakba. “Even Abu Sami told me that his grandfather used to stash [gold] within the well,” says Banay. “Then other people in the village wanted them to keep theirs. When they built the housing projects, they put all the construction waste of the demolished houses into that well, sealed it, and built a building on top of it.”

Margalit, a resident of Kfar Shalem interviewed in Banay’s film, was recruited to the Irgun, the underground pre-state Zionist paramilitary group, at the age of 14 because she spoke fluent Arabic. She says that due to Salama’s strategic location, this was “the place that needed to be cleansed first of all” in 1948. She began operating there as a spy, but after a while she told the Irgun commander and future prime minister, Menachem Begin, that this was a village of farmers that posed no threat.

This didn’t stop the Zionist militias from expelling the residents in 1948. “They fled in a terrible hurry,” she says in the film. “They [even] left food on the stove.”

One of the scenes in Banay’s film documents a meeting between Margalit and Abu Sami. “There was nothing to do but sit next to them and watch, because they shared an amazing sense of common destiny,” he says. “They spoke like they have known each other for a century, no blame, nothing,” he continued. “She had helped uproot him, [but] he felt no grudge against her, no hatred — it was amazing to see.“

“I keep saying that ultimately, had they let the Mizrahim negotiate with the entire Arab world, it would have turned out much better,” Banay says. “You have a shared culture that helps bridge gaps much more than having a European arrive and negotiating in a completely different style, without understanding all these little nuances of respect.”

The text includes excerpts from “Remembering Salama,” a booklet produced by Zochrot for the purpose of documenting the places that Israel occupied and destroyed during the Nakba since 1948.

A version of this article was first published in Hebrew on Haokets. Read it here.