Both the economic and political elite in Israel benefit from the occupation in different ways. The longer the occupation persists, the wider become the gaps between these two ‘1 percents’ and the rest of the country.

By Shlomo Swirski

What is the cost to Israel of the occupation? And who in Israel is paying it?

Discussions of Israel’s military rule over the Palestinian territories conquered in 1967 — now marking 50 years — usually revolve around moral, military, diplomatic, and legal matters.

The impact of the conflict on Israeli society — on the standard of living, economic growth, inter-ethnic and Arab-Jewish relations, and disparities between the center and the periphery — is rarely considered. Political, academic, and media discourse often takes place as if the occupation has no real connection to what is happening within Israeli society.

This report seeks to add a vital and missing dimension to the discussion by focusing on some of the critical social and economic repercussions of the occupation and of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

What emerges from this analysis, it can already be said, is that the main losers of this reality are low-income Israelis, both Arab and Jewish. These citizens of Israel are harmed by the competition with cheap Palestinian labor, which also opened the door to cheap labor from other countries; by the fiscal austerity policies designed to convey to the international business community the message of fiscal stability, despite the frequent violent clashes; by the effect of the belt-tightening measures on the social safety net and the major social ministries — education, health, and welfare; and by the need to pour increasing amounts of money into security matters instead of social services.

The occupation adversely affects economic stability, creating growth conditions that are sometimes extremely volatile, particularly during extended periods of violence, such as the two Intifadas and Protective Edge Operation in the Gaza Strip in 2014. This instability hurts not only low-income Israelis, but also large corporations and high income earners, the difference being that the governments of Israel have done everything in their power to shield the wealthy by lowering personal income and corporate taxes, reducing the cost of credit, and crafting policies that reduce labor costs.

Inequality in Israel has escalated over the last three decades, and is today among the highest in the western world. This is generally attributed to the neoliberal policies that have prevailed since the 1985 Economic Emergency Stabilization Plan. Particularly severe neoliberal policies were instituted during the second Intifada, concurrent with one of the longest economic crises in the history of Israel. Without the sense of emergency created by this Intifada, such extreme measures would probably not have been instituted, or they might have been more moderate and gradual. This is the most glaring example of the link between neoliberalism within Israel and the long-standing military occupation across the Green Line.

Not one, but two ‘1 percents’

In 2010, Israel was accepted into the OECD, the club of rich countries. Out of 34 member states, Israel ranks 22nd on per capita GDP. It ranks even higher — 19th — on the UN’s Human Development Index, which takes into account not just economic performance, but also health, education, and gender equality indicators. Several Israeli schools rank among the two hundred best universities in the world. Much of Israeli industry and the service sector enjoy a high-tech infrastructure. Israel pioneered the development of drones and maintains civilian and military space satellites. Indeed, most international high tech companies conduct R&D in Israel, burnishing its image of a “start-up nation.”

But at the same time, Israel has the highest poverty rate of OECD countries, and one of the highest rates of low-wage earners, defined as workers who earn no more than 2/3 the median wage. Close to half of all Israeli 17-year-olds have not matriculated. Most areas of Israel are defined as being in the social and economic periphery, far from the heart of “start-up nation” socially and economically.

How can one explain these two conflicting faces of Israel?

From a historical perspective, the main explanation resides in the 1948 encounter in the new state of the three main groups that compose Israeli society:

Veteran members of the Zionist community, most of European descent, held the governance, command, and administrative reins of the new state. Later, with the development of industry, services, and finance, most executives of the new business sector hailed from this stratum.

The Palestinians who became Israeli citizens were the remnant of those defeated in the war, a community that had lost its leadership and most of its land, whose members had once been farmers and who now became the farm hands and laborers in the fields and factories belonging to Jews.

Mizrahim, who immigrated to Israel from Arab countries under circumstances similar to those of refugees, were dispatched to distant towns devoid of proper schools and health services, and could find only low-paying jobs in traditional industries, like textiles and food production.

Israeli society underwent many changes in the three generations that followed 1948, some due mainly to state investment in economic development, housing, education, and health. The Six-Day War led to expansion of the military and the defense industry; population growth necessitated a larger civil service, more schools, and increased health services; and all these created a fairly large middle class, one that included Mizrahim. However, the seeds of inequality planted during the early years bore fruit: In 2015, sixty-seven years after the establishment of Israel, Ashkenazi employees were earning 31 percent more than the average wage, Mizrahi employees only 14% more than the average wage, and Arab employees 38% less than the average wage.

In 1985, almost forty years after the founding of the state, the Israeli government adopted a neoliberal socioeconomic approach that exalts the “free market.” Thus, it gradually shed all responsibility for economic and social initiatives and passed the economic baton on to what had emerged as the corporate elite. The results were, inter alia, the privatization of state corporations and services, rising executive salaries, decreasing labor costs, reduced taxes, and a growing burden upon households for financing social services.

The change of direction in 1985 further deepened the disparities of 1948 for a number of reasons: One of the factors that until then had fostered inequality, ethnic identity, was now compounded by a second factor — money and wealth.

If, prior to 1985, the hope of reducing inequality rested upon government policies, thereafter it was pinned on economic growth: Growth was supposed to create jobs, raise the standard of living, and ultimately reduce inequality. In practice, however, the outcome was different: Privatization led to the creation of a stratum of capital owners, managers, and providers of professional services, who together comprise the upper income decile. Within that decile, a top 1 percent began to emerge. When there was growth, much of the profit rose to the top. The middle class, which formerly had benefited from the expansion of the state and the military, began to shrink, while the stratum of persons earning minimum wage or less became entrenched.

This is a well-known tale, epitomized by the protest movements that rose over the years: the Mizrahi protest in Wadi Salib in 1959; the Mizrahi “Black Panthers” of 1971; the Arab “Land Day” demonstrations in 1976; and the “social justice protest” of the largely Ashkenazi middle class in 2011.

But the story of Israeli inequality is larger. In 1967, halfway between 1948 and 1985, Israel conquered and occupied the Palestinian territories, regions that, since 1948, had been ruled by Egypt (the Gaza Strip) and Jordan (the West Bank). Israel held on to the new territories, and the Palestinians engaged in political and military resistance, epitomized in constant clashes, the best known of which are the first and second Intifadas.

Many Israelis, perhaps the majority, relate to the occupation and the ongoing Palestinian resistance as a political or military issue unrelated to the socioeconomic story recounted above. This is an unfortunate misconception: “Occupation maintenance” is a very expensive enterprise, one that undermines economic growth and hampers the state’s ability to invest in development of the periphery, upgrade educational services, and raise the standard of living for all Israelis. The periodic clashes necessitated a substantial financial investment in the army and large expenditures on each and every confrontation. Although the “start-up nation” continues to prosper, these clashes make it difficult for other Israelis to join in the prosperity.

The effort of maintaining political, military, and economic rule over the occupied territories has been Israel’s major preoccupation since 1967. This issue tops the public agenda, brushing aside socioeconomic needs. A Palestinian state or unilateral annexation? Evacuation of Amona or its expansion? One state or two? Two states and one homeland? These issues are what distinguish the political parties and determine election results, preoccupy the state leadership day and night, and affect Israel’s international standing. The “social” issues and those who care about them capture public attention only rarely, generally around specific events, such as publication day of the annual poverty report.

Constant tension between the two agendas — the socioeconomic and the political-security — can be illustrated by the concept of “the top 1 percent,” associated with the 2011 “Occupy Wall Street” movement in the United States.

The American slogan referenced the wealthiest 1 percent of the population, epitomized by Wall Street in New York. At the same time, it has become apparent that Israel has an economic 1 percent of its very own. This 1 percent conducts business from the luxury high-rises in Tel Aviv, and often also lives there. This is a stratum of some 85,000 people (1 percent of the population of 8.5 million), who became exceedingly wealthy in the course of the last twenty years, outpacing other Israelis, including fellow members of the top decile.

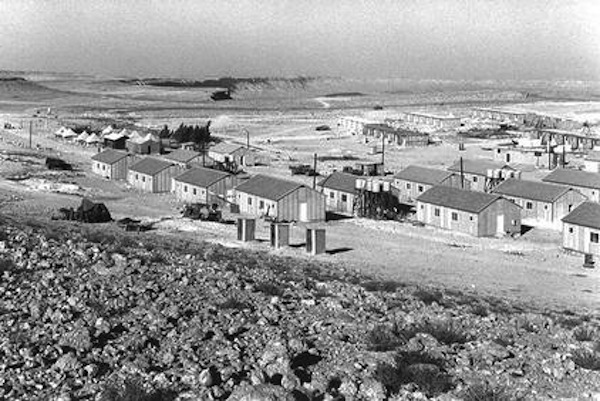

But unlike the United States, Israel has another top 1 percent, and this group is political — namely, the so-called “ideological” settlers who occupy the hills of Samaria and Judea. The political leadership of these settlers has become a powerful pressure group able to impose a political veto on any diplomatic initiative that involves evacuation of Israeli settlers from the occupied territories and, indeed, any political accommodation that includes an independent Palestinian state. Thus, they exact a steep price, not just in terms of bloodshed, political issues, and security, but also in terms of the economy and society.

The size of this group is commonly estimated at 60-80,000 people — a number comparable to the top economic 1 percent. While this 1 percent vetoes every move toward a political agreement and settlement evacuation, thereby contributing to the economic instability characteristic of Israel, the other 1 percent vetoes every initiative to raise taxes on the wealthy and expand the welfare state, thereby perpetuating and exacerbating inequality in Israel.

The socioeconomic 1 percent evolved and consolidated largely after the state turned away, in 1985, from its tradition of state developmentalism that included national missions such as immigrant absorption or guaranteed full employment. However, this did not prevent the state from embarking on a new national mission – not improving the lives of the “other Israel,” but rather benefiting the “Greater Land of Israel”. Actually, the 1985 policies never crossed the Green Line. On the other side, the state invested huge sums and countless resources in the new national mission, thereby creating a second, political 1 percent.

The two 1-percent groups are not identical, of course: One owns a great deal of property within Israel and outside it, and can relocate in times of trouble; the other squats on hills, claiming divine title to the land, and will wage battle when threatened. One has been out of touch for years with the 99 percent staggering under a mortgage and the cost of living, and feels at home in global financial circles; the other sees itself as the advance guard in a never-ending national-religious struggle and has been out of touch for years with the 99 percent who want a normal life without a Palestinian conflict or military reserve duty. One supports political accommodation in hopes of economic stability and accelerated growth, but feels quite comfortable with the status quo; the other opposes political accommodation and knows how to exploit violent clashes to elicit legitimacy for its cause.

Under the slogan “the business sector trumps the public sector in everything,” one is actively striving to weaken the public services established in Israel over the previous century, reduce the state budget, privatize government services, and establish private schools and health services that benefit mainly themselves. Meanwhile, the other manages to avoid the fallout from neoliberal policies and enjoys enhanced state allocations for security, bypass roads, subsidized education, and the financing of municipal services. One cites each violent episode as proof positive that there is no partner for negotiations, while the other benefits from the fact that the government deals with the economic crises resulting from the uprisings with recipes taken from the handbook of neoliberal economics.

And this, too: Some members of the economic 1 percent also profit from the enterprises of the political 1 percent — construction companies, defense contractors, security firms.

The state tries to remain in the good graces of both groups. It curries favor with one by offering cheap credit, cheap labor, low taxes, and toothless regulation; while it panders to the other by providing the comprehensive, daily protection of the strongest army in the Middle East. One is praised as the standard bearer of growth; the other is embraced as the latest embodiment of the Zionist pioneering spirit.

Needless to say, both 1 percent groups remain distant from each other, socially and politically. During the Rabin government, most of the economic 1 percenters were avid supporters of the Oslo Accords, while the political 1 percenters fought and incited against it, until an unknown emerged from that camp to assassinate the prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin.

Despite the differences and the distance between them, both top 1-percent groups are part of one national complex. To understand how it is possible that within Israel, a “start-up nation” exists side-by-side with “the other Israel” — to revive a term from the 1960s and 1970s — one must take both 1-percent groups into consideration. The answer to the question of why the gap is so vast between “start-up nation” and the rest of Israel can be found in the ability of these two 1-percent groups to shape the public agenda and prevent measures that would reduce inequality and bring the entire population of Israel, or most of it, within the borders of the oft touted “start-up nation.”

Dr. Shlomo Swirski is the academic director of the Adva Center.