Expelled by Israeli forces from the Negev, then forced to live next to a garbage dump, the Jahalin Bedouin have lost their ancestral homes and their traditional way of life. The impending forced displacement of Khan al-Ahmar is just the latest struggle in the Bedouin tribe’s history of dispossession.

Just outside the Palestinian town of Eizariya in the occupied West Bank, on the side of a busy highway, sits a set of small trash-strewn plots. Bent remnants of metal pipes protrude from piles of crumpled cans and broken bottles. Shredded plastic bags flap in the wind as cars rush by. Garbage trucks unload their toxic cargo at the Abu Dis dump just 500 meters away. The smell of burning rubbish makes the air sharp.

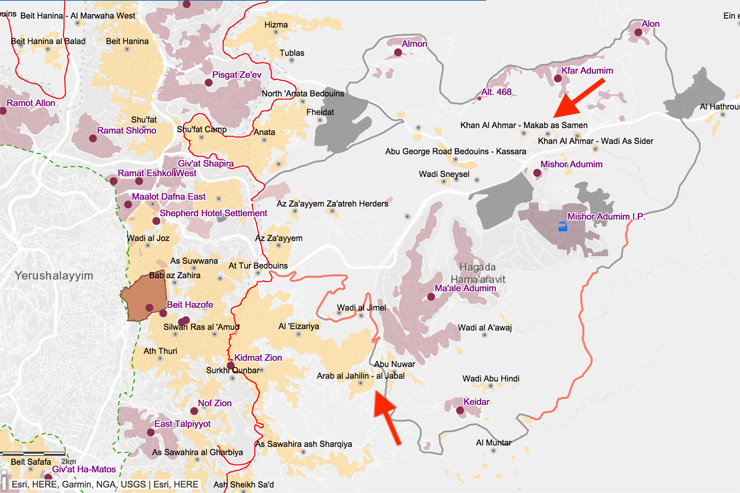

This area is known as Jahalin West, where the Israeli government plans to forcibly transfer the 181 residents of Khan al-Ahmar, a Palestinian Bedouin hamlet facing imminent demolition.

Israel’s High Court ruled in late May that the government could relocate the inhabitants of Khan al-Ahmar despite their opposition to the planned relocation site. As of this writing, the residents of Khan al-Ahmar say they plan to stay on their land — even if army bulldozers demolish their homes and the school that serves the village’s children and those from the surrounding villages.

“Would you take your family to live in this area, near the dump?” asks Eid Abu Kammis, the Khan al-Ahmar community’s spokesperson, a few days after the court’s decision.

What exactly awaits the Bedouin of Khan al-Ahmar remains uncertain. If the army were to demolish the village tomorrow, “it would be a kind of standoff and the question would be who would capitulate first,” says Jeremy Milgrom, a member of Rabbis for Human Rights who has worked with Bedouin communities in the area for two decades.

If the residents of Khan al-Ahmar stay on their land against the government’s wishes, the army could declare a closed military zone and arrest them, Milgrom adds. They could also disperse and look for new land elsewhere.

As of now, no accommodations have been made at the site of Jahalin West ahead of the planned demolitions. No infrastructure, water, or electricity. No temporary modular homes await them like the ones Israeli settlers from the Nativ Avot outpost moved into Tuesday after Israeli police evicted them.

Khan al-Ahmar has been fighting the Israeli government’s attempts to demolish the village and relocate its inhabitants for nearly a decade. In doing so, it has become internationally recognized site of opposition to Israel’s forced transfer of Palestinians out of Area C of the West Bank, which is under full Israeli military and civil control, and where Palestinians are effectively prohibited from building houses and schools. Other villages in Area C, such as Susiya in the South Hebron Hills, have been the focus of similar campaigns against Israel’s demolition and forced displacement plans.

In the past, pressure by American and European diplomats succeeding in staving off demolitions that seemed imminent. In the weeks since the High Court’s decision, Khan al-Ahmar has again become a site of frenzied activity, including protests, press conferences, and Israeli and international activists and journalists driving up and down the unpaved road that leads to the village.

The struggle of Khan al-Ahmar is the latest chapter in the Jahalin Bedouin tribe’s 70-year-long history of dispossession and forced relocation by the Israeli government. Across the road from the litter-filled plots intended for Khan al-Ahmar’s residents is the small town Arab al-Jahalin, also known simply as al-Jabal — in Arabic, the mountain. An uneven array of cement houses and half-paved roads, al-Jabal is home to roughly 1,500 people, all Jahalin Bedouin who have been expelled from their villages in the surrounding hills over the past two decades.

Before Israel’s establishment, the Jahalin lived in the area of Tel Arad in the Negev, located in present-day Israel. Following the 1948 war, the Israeli military forced them out of their villages and into the West Bank; they settled in the pink, rocky hills of what today is known as Mishor Adumim. When Israel occupied the West Bank in 1967, the Jahalin again found themselves at the mercy of the IDF.

In the 1990s, the Israeli government came to view the Jahalin, who mostly lived in unrecognized villages without running water or electricity, as an obstacle to settlement expansion plans. Beginning in 1997, Israel demolished three of their villages and forcibly transferred the inhabitants to what is now al-Jabal, where just 12 Jahalin families were living at the time.

After being pushed out and bused to their new homes in al-Jabal, each family received a shipping container to live in, where they lived for over three years. A 1998 United Nations report condemned “the manner in which the Government of Israel has housed these families in steel container vans in a garbage dump in Abu Dis in subhuman living conditions.”

Israeli authorities displaced another 35 Jahalin families in February 1998, and in 2007, 50 more families living on the outskirts of al-Jabal were incorporated without being displaced.

Salah, a middle-aged man with a wide smile, was a young man when he was forcibly transferred to al-Jabal in 1998. The bulldozers came to the village along with hundreds of soldiers and police, he recalls. “They destroyed everything.”

A short film made in the late 90s about the Jahalin documents the demolition: police dragging people from their homes, shoving and beating them, army bulldozers turning the village’s shacks into piles of rubble. When they arrived at al-Jabal, Salah remembers, there was nothing; it took more than two years to build proper housing and more than five to connect the new houses to electricity.

“Even now, we’re still not happy,” Salah says, 20 years after the expulsion. “We miss our old way of life.”

Mohammed, one of Salah’s sons, pulls out his phone to show us a picture of his father tending his flock. “This is dad with the sheep, he wants to live like that.”

The Israeli government’s forced expulsion of the Jahalin from their villages has done more than simply relocate them; it has destroyed their traditional way of life. A people accustomed to freely herding goats and sheep up and down the hills of the Judean desert must now raise its livestock confined to pens of just a few square meters.

The loss of the freedom required for shepherding means that the community has lost what was once its main source of livelihood. In the years since the Oslo Accords, the Jahalin have been forcibly transformed from a mobile, pastoral community into an urban industrial labor force.

Today, most of the men in al-Jabal work as manual laborers in the neighboring town of Eizariya or in the surrounding Israeli settlements, building the homes of the people who expelled them from theirs.

Iyad, 30 and a father of two, was a child when Israel demolished his village to build a new neighborhood in the settlement of Maale Adumim. He points to the parallels between his village’s destruction and the fate that awaits Khan al-Ahmar.

“Then it was Ramadan, now it is Ramadan,” he says. Khan al-Ahmar, Iyad adds, “is like a refugee camp.” And he is not optimistic about its future. “What happened to us will happen exactly to them.”

UN officials have condemned the plan demolition and forced transfer of Khan al-Ahmar. The UNRWA Director of Operations in the West Bank, Scott Anderson, warned that the Israeli government’s plan, if executed, “would be a grave breach of the Geneva Convention.”

A few days after the court gave a green light to demolish Khan al-Ahmar, Eid Abu Khammis sits in a tent where he has been welcoming international activists and journalists all day. His phone in one hand, a cigarette in the other, he checks the news, shaking his head while tapping ashes onto the ground.

The village is quiet, perhaps for the first time since the morning. A sense of despair begins to fill the silence. Then Abu Khammis looks up and gestures, lit cigarette in hand, toward the red-tile roofs of Maale Adumim in the distance.

“You see those,” he says, “I was here long before those towns.”

Oren Ziv contributed to this report.