Thousands of Israelis marched in Jerusalem last week to mark the beginning of Pride Month, with the more well-known Pride Parade in Tel Aviv commencing today and tomorrow, in which over 150,000 people are expected to participate. While the two parades and the many events held between them are widely touted as evidence of Israel’s place as a leader of tolerance and liberal values in the Western world, this image masks a much darker reality about LGBTQ rights and safety, especially for queer Palestinians.

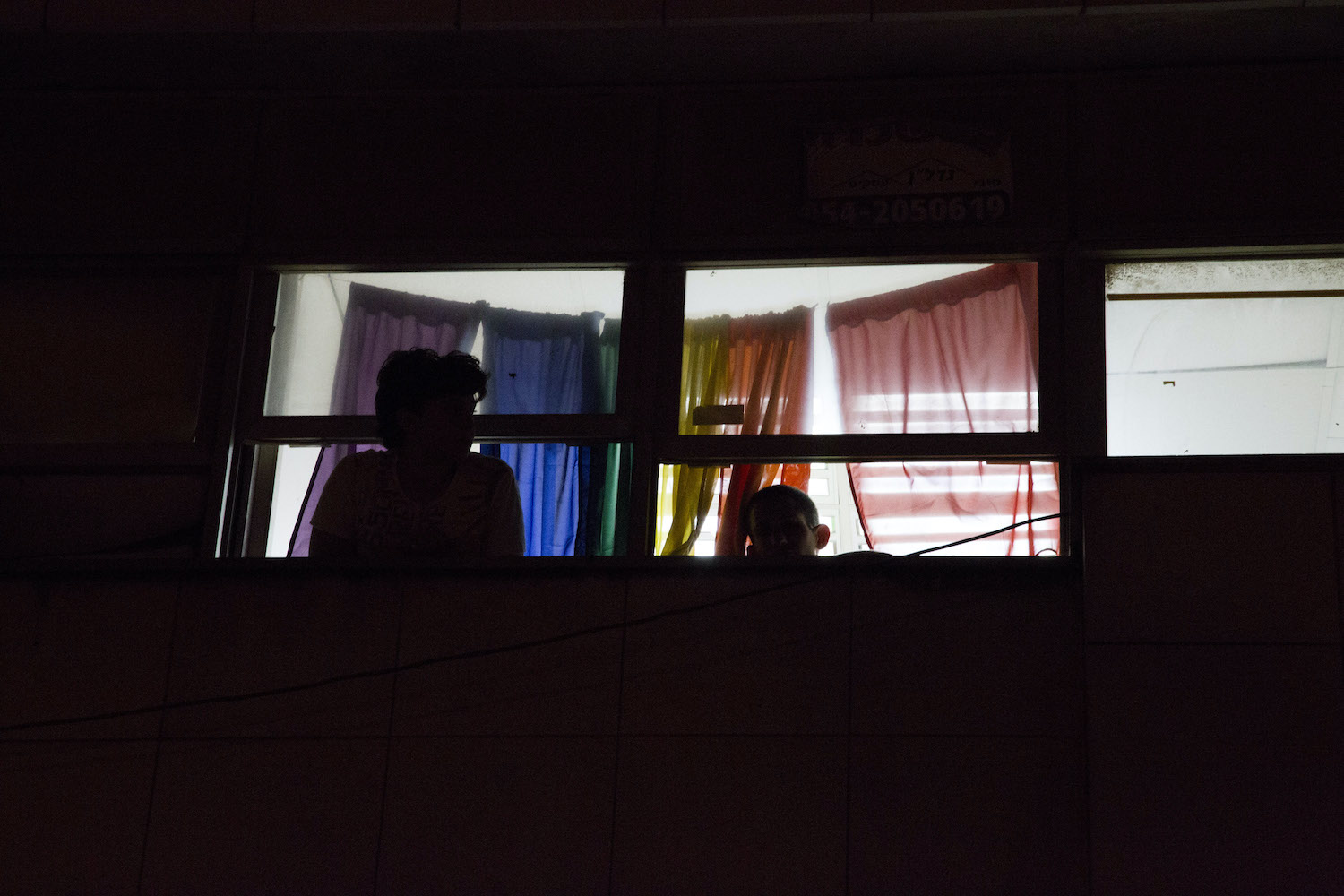

For many LGBTQ Palestinians, Pride Month in Israel functions as a façade that obscures the deep injustices on the ground. MC, a Palestinian trans woman, has personally experienced this. She asked to be referred to by this pseudonym, and to obscure other identifying details in her story, fearing that using her full name would compromise her identity with Israeli authorities or with those who may want to harm her for her sexual identity.

In an extensive interview with +972, MC shared her story and the struggles she has faced as a Palestinian trans woman seeking shelter and freedom in Israel. As her account illustrates, Israel’s supposed tolerance of the LGBTQ community only goes so far: Palestinians like MC, many of whom face discrimination and rejection within their own communities, are structurally denied the freedom and acceptance that Israel advertises.

MC hails from a small Palestinian community where being trans led to her alienation and ostracization, as is the case for many LGBTQ people living in other small, traditional, or conservative communities around the world. Growing up raised as a “boy,” MC said she felt jealous of women; she can’t remember ever feeling that she had been born into the right body or gender. Her family sensed this, too, even at a young age.

She laughs as she recounts this: “My parents would leave [the house], and I would quickly put on girls’ clothes and makeup and dance while they were out, and then change back into boys’ clothes just before they returned. Once, when I was small, my mother returned home early and found me dancing in front of a mirror in a girly way. She was very angry and yelled at me to act ‘like a man.’ At one point, my brother, who always had anger issues, threatened me and held me over the edge of a roof because I was ‘like a girl.’”

But MC had no desire to be “manly.” “The lives of men seemed very narrow,” she explained. “Men are not truly free. So much is expected of men. They can’t have emotions, but must be strong and powerful.”

As a teen, MC began hearing claims about Israel being a “paradise” for gay and trans people, and longed to find solace in such a place. Later, as a young woman, her close friend, knowing that MC had no real future in their community and worrying about her safety, sent her images and information about LGBTQ life in Israel — likely the kind that Israel actively promotes in its public relations (“hasbara”) campaigns.

Initially, MC did not make any plans to live in Israel. But one day, after a night out with friends, MC says she was less careful than usual and posted videos of herself dancing and acting openly effeminate. Life in her small community subsequently became impossible, and she faced threats from both relatives and neighbors.

Her brother, who had frequently threatened her with a knife, now cut her and made it clear he intended to do more. She first tried to escape to a family member living in a more urban Palestinian area, but after other relatives there threatened her with guns, she finally decided to try and escape to this purported “paradise.”

MC managed to make her way to Tel Aviv, crossing the border without a permit, and spent her first night on the beach, terrified that the police would catch her and send her back. Soon after her arrival, she was referred to an Israeli hostel for LGBTQ runaways, one of a handful of such safe houses in Israel — a place she quickly discovered was hardly the safe shelter she was seeking, but rather yet another place of control and punishment. The rules and regiments were excessively strict, the Israeli staffers were dominating, and the atmosphere felt stifling. MC noted that the hostel contained mostly Jewish Israelis, who had also sought refuge from their own communities and families, and that they experienced the same mistreatment.

Layers of control

The hostel was just the first taste of many layers of structural violence MC would slowly realize was her new reality. Though there are certain systems in place in Israel that are supposed to help LGBTQ people like MC, many of them double as mechanisms of control, conditioning the assistance they provide on the victim’s forgoing of their agency.

While MC chose not to go deeply into the subject out of concern for her safety and legal situation, other queer activists and individuals commonly point to a small number of lawyers, well-known to gay and trans Palestinians, who are supposed to help people in their situations. However, these attorneys do much more than merely practice law: they act as gatekeepers in full control of matters of life and death for LGBTQs. If the lawyers like a client, they will go out of their way to help them; when someone displeases them for whatever reason, the lawyers can destroy that person’s chance of achieving safety and freedom.

These lawyers are often the point of contact between LGBTQ Palestinians and the Israeli permit system or UN asylum agencies. Israel’s permit regime — an oppressive bureaucracy that governs the lives of all Palestinians — is one of the most glaring examples of the systemic violence and control Israel uses against gay and trans Palestinians. Al-Bait Al-Mokhtalef (The Different House), a group that works with LGBTQ Palestinians, told +972 that there are around 150 queer Palestinians formally applying for asylum in Israel.

MC received a permit to stay in Israel shortly after her arrival, and while it can be renewed, she never knows for how long — it could be one month, or it could be six — and it may not be renewed at all. Whenever her time limit is up, she must travel to the Ma’ale Ephraim/Tayasir Checkpoint, in the Jordan Valley in the occupied West Bank, for an interview with the Israeli authorities. On one occasion, MC says, her permit was denied simply because she had seemed “too confident,” which the interviewing officers told her made her suspicious. The message was clear — she should be anxious, fearful, and needy; a strong Palestinian was a threat.

“The permit is their weapon,” MC explained. “I have to be careful of everything I do. I can’t seem too confident. It’s better to seem afraid of them. They like that better.”

The permit regime is weaponized by Israel in another crucial way: planting suspicions in Palestinian society using sexuality to divide Palestinians. Due to the dominating and invasive presence of Israel’s intelligence apparatus in Palestinian society, many Palestinians assume that LGBTQ people who receive permits have — out of desperation or threats — agreed to collaborate with Israeli security forces. As a result, gay and trans Palestinians are subjected to further suspicion and stigmatization, further alienating them from their own people. In this sense, sexuality is used as another way to divide and conquer.

Sometimes, there are cases in which gay Palestinians are indeed blackmailed by Israeli authorities, only serving to confirm public suspicions. This is part of a broader policing of Palestinians, in which Israel’s security establishment can, when it wishes, gain access to even the most intimate details of Palestinians’ lives to use as leverage.

This is not only true of LGBTQ Palestinians, but anyone with a secret or personal dilemma, whether an illicit affair, drugs, or cheating a family member of money. As one former intelligence official told the Guardian in 2014, “Any Palestinian may be targeted and may suffer from sanctions such as the denial of permits, harassment, extortion, or even direct physical injury … Any information that might enable extortion of an individual is considered relevant information.”

This was the case with 23-year-old Zuhair al-Ghaleeth from Nablus: Israeli security forces used footage of him having sex with another man to pressure him into gathering information on the Lion’s Den, a Palestinian armed group; militiamen eventually captured and interrogated al-Ghaleeth, forcing him to confess, before killing him.

‘I just want to be free’

In addition to Israel’s regime, MC described the United Nations as yet another colonial body of institutionalized control over LGBTQ Palestinians. Her interactions with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), responsible for supporting or assisting those seeking refuge and asylum in other states in exceptional circumstances, have become so mired in bureaucracy that they reach near-absurd heights.

To approach the UN agency, Palestinians in MC’s situation are given a phone number to call in order to set appointments. She has called for over a year and is always told that there are no appointments for such cases in the near future, and that she should try again later. She ultimately decided to go to the UNHCR’s main office in Tel Aviv escorted by a local NGO worker who could attest to MC’s need for asylum in a third country, but they were told she could not physically enter their office, and was simply given the same number that she had been calling for months.

Even if MC ever succeeds in setting up an appointment, the process of attaining asylum status in a third country is likely to take several years. The long waiting period is not merely a legal limbo: for many, it is a state of constant or escalating danger, and can even be a death sentence, as was the case for Ahmad Abu Murkhiyeh, a gay Palestinian who was brutally murdered just before he was finally set to be granted asylum. MC noted that the despair felt by those waiting for indefinite periods can sometimes drive them to suicide.

When +972 asked UNHCR about the lengthy asylum process for queer Palestinians and the difficulties with getting appointments, a spokesperson for the agency responded: “A Palestinian wishing to apply for protection in Israel must do this with the Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories [COGAT, a branch of the Israeli military that governs civilian affairs in the occupied territories]. This is an independent State procedure. UNHCR has no role in this procedure. There are a few organizations in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem which are active in providing support to LGBTI people, including Palestinians … UNHCR operates a support telephone service and we are always available to provide professional advice.” (+972 also reached out to COGAT for comment; no response was received at the time of publication).

On paper, MC is now able to work in Israel, thanks to a recent change following a 2022 High Court ruling on a petition filed by several human rights groups on behalf of LGBTQ Palestinian asylum seekers. In reality, though, it remains nearly impossible to find stable employment, both due to the lack of an Israeli ID and her distinct appearance as a trans woman. While MC doesn’t seek an Israeli ID, she wants to be able to live and work without the constant fear of losing everything or suffering violence.

Most read on +972

“I just want to be free,” she said. “Maybe go to Canada or Sweden. A place where I can transition in freedom.”

But it remains unlikely that MC will achieve this freedom anytime soon. She currently lives in an Israeli city where she is caught in a perpetual trap of dependency — dependency on the colonial Israeli authorities, which use her sexuality as a means of control; dependency on an immobile UN to one day grant her a future elsewhere; and dependency on various, sometimes well-meaning, people and relationships who sometimes use her vulnerability or power imbalance to make her behave or do things as they wish.

Colonialism and sexuality

“Pinkwashing” has become a common term to describe how Israel uses its image of tolerance for the LGBTQ community as a means of whitewashing its crimes against Palestinians. According to writings published by alQaws, an organization that promotes sexual and gender diversity in Palestinian society: “Pinkwashing is the symptom, settler-colonialism is the root sickness. Recognizing pinkwashing as colonial violence can help us understand how Israel divides, oppresses, and erases Palestinians on the basis of gender and sexuality.”

Pinkwashing is one mechanism among many that Israel uses to distract from the apartheid regime it upholds. However, as MC’s story — and countless others like it — make clear, Israel doesn’t merely use LGBTQ issues as a cover-up. It has a secondary function as a weapon of domination.

Israel’s current far-right government — a coalition of nationalist and religious parties that took power half a year ago — has made the vulnerable position of the LGBTQ community, even within Jewish society, impossible to ignore. After running on a blatantly homophobic platform, the anti-LGBTQ party Noam now has a member of Knesset, Avi Maoz, who last week was reinstated as a deputy minister and appointed as the head of a new “Jewish Identity Authority,” which will involve supervising school curriculums and extra-curricular activities.

In addition, the government’s efforts to overhaul and weaken the Israeli Supreme Court would further leave marginalized groups, including the LGBTQ community, at significant risk and lower the already dismal chances of defending their rights and achieving remedy when harmed. Members of the government have already declared their intention to amend an anti-discrimination law that could allow doctors to deny medical care to LGBTQ patients on religious grounds. And while last week’s Pride Parade in Jerusalem took place without major incident, participants had significant concerns, noting the incitement from extreme right politicians.

Similarly, there are many conservative and patriarchal forces in Palestinian society that continue to promote the idea that being gay or trans is taboo, or “haram” (forbidden). From ordinary people to artists to public figures, LGBTQ Palestinians still face threats of violence, extortion, demonization, and smear campaigns from their own community. Yet there are also many progressive elements of Palestinian society that are actively working to change this from within, with new ground being broken in civil society, cultural production, and public discourse.

However, under Israeli rule, these progressive groups are routinely prevented from expanding and organizing to their full potential. In 2021, for example, Israel outlawed six prominent Palestinian human rights groups as “terrorist organizations,” including Al-Haq, a leading NGO that documents violence and abuses against Palestinians, including internal violence targeting the LGBTQ community. As investigations by +972 and Local Call showed, despite attempting to convince foreign diplomats otherwise, the Israeli authorities still have no serious evidence to justify their accusations.

Moreover, Israel’s wider policies of fragmenting Palestinians from one another, both geographically and socially, has rendered open communication and political activity a constant uphill battle. The work of progressive Palestinians, including LGBTQ groups, becomes challenging, if not impossible, under such colonial conditions.

And yet, gay and trans Palestinians like MC are not simply vulnerable or weak. MC is a strong agent of change, facing obstacles with her form of “sumud”, or steadfastness, refusing to let her spirit be crushed. While MC does not view herself as an activist, and is understandably hesitant to openly criticize all the structures responsible for her predicaments, her story makes one thing abundantly clear: the fight against apartheid and the fight for LGBTQ rights are inseparable, an overlapping pursuit of justice and liberation for all.