This article was published in partnership with Local Call.

Israel’s creeping annexation of the West Bank is by no means a new story. By now, and especially after the Netanyahu-Trump years, its contours are well known: Israel has steadily been taking over more and more Palestinian-owned land in the occupied territories in order to build and expand Jewish settlements and prevent the possibility of a Palestinian state. But what happens when those settlements become so powerful that they start annexing land within the Green Line?

Documents attached to a recent appeal to the Israeli Supreme Court highlight a little known fact: a number of West Bank settlements control vast agricultural lands inside the Green Line, which they received from Israeli authorities as far back as the 1970s.

The documents were filed by Har Amasa, a moshav in southern Israel, which petitioned the court to block the establishment of a nearby wind farm, due to the noise pollution and health issues it may cause. Among the respondents to the appeal were Carmel and Beit Yatir, two West Bank settlements in the South Hebron Hills — an area in which Palestinians frequently face brutal settler violence. It turns out that the wind farms are supposed to be built on land that the state handed to those settlements for agriculture.

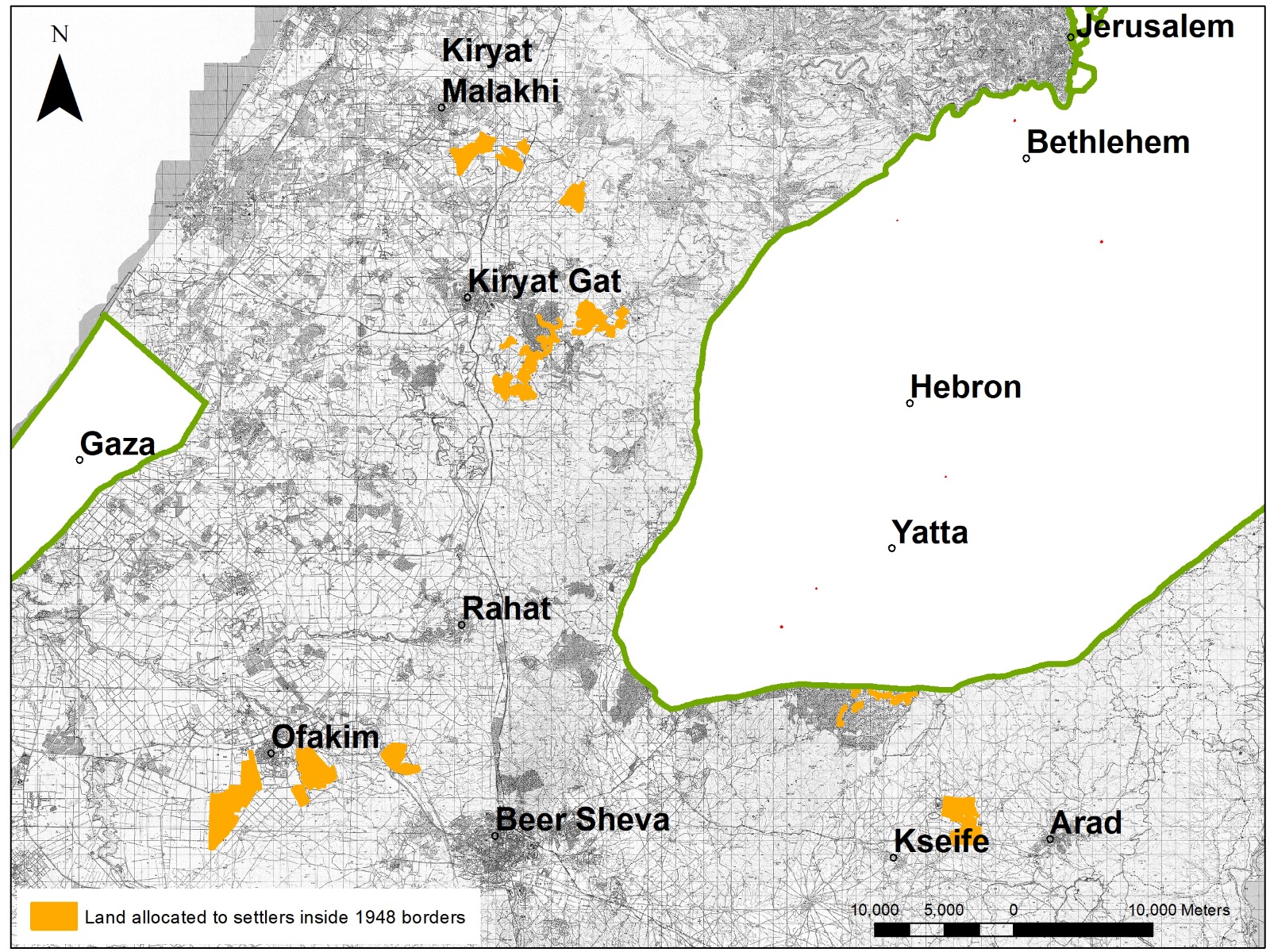

Although this is not a new phenomenon, it is unfamiliar to most Israelis. According to information provided by the Israel Land Authority (ILA) to Dror Etkes, an Israeli activist who monitors settlement construction with his NGO Kerem Navot, seven settlements — Kfar Etzion, Migdal Oz, Rosh Tzurim, Ma’on, Carmel, Beit Yatir, and Mevo Horon — have contracts with the ILA to allow the cultivation of more than 38,000 dunam [9,390 acres] inside the Green Line.

But the real figure seems to be higher. According to a table of land allocations on the ILA’s website, six of these settlements (excluding Horon) hold more than 50,000 dunam [12,355 acres] within the Green Line. These numbers may also be incomplete, since they do not include areas handed over for seasonal cultivation.

The figures are particularly striking given how little agricultural land those six settlements own inside the West Bank itself — around 2,000 dunam [494 acres] each — meaning more than 95 percent of these settlements’ agricultural land is located within the Green Line. In other words, without the additional land inside Israel, these settlements would not have had a real possibility of sustaining their agricultural production.

Because the Gush Etzion settlements — Kfar Etzion, Rosh Tzurim, and Migdal Oz — are defined as kibbutzim, and the South Hebron Hills settlements — Carmel, Ma’on, and Beit Yatir — are defined as cooperative moshavim, they all fall under the definition of “planned agricultural settlement.” According to the Ministry of Agriculture’s Land Committee, which recommends to the ILA to whom state land will be allocated, any planned agricultural settlement can apply for long-term leasing of agricultural land without a tender.

Not a single Palestinian village or town in Israel falls under the definition of a “planned agricultural settlement,” leaving Arab farmers with almost zero chance of receiving land under such favorable conditions.

The allocated agricultural land is located quite far from the settlements themselves; this is not unusual for communities defined as kibbutzim and moshavim, many of which have also been given state land far from their location. Still, the land given to the Gush Etzion settlements extends about 50 kilometers to Kiryat Gat, while the areas handed over to the South Hebron Hills settlements extend to the area of Ofakim, a distance of 70 kilometers.

‘Capturing territory is a national mission’

The decision to allocate land inside Israel to West Bank settlements is not new. The Gush Etzion settlements were most likely given the land in the early 1970s, while the three settlements in the South Hebron Hills were allotted the territories in the late 1970s. “We started cultivating the land in 1979,” says Uri Zilberman, who heads Gadash Hebron Hills, a company based in the occupied West Bank that specializes in field crops.

According to Ariel Shinkolevsky, the head of Gadash Etzion — which oversees the Gush Etzion settlements’ agricultural areas — agriculture within the Green Line is one of the main sources of income for his settlement, Migdal Oz.

“In the past, [settlers] would take vans [to the agricultural land] in the morning,” says Shinkolevsky. “Today there are not many workers from the kibbutz who come. It has become an abstract matter for the members.” Most of the workers in Gadash Etzion’s farms are temporary migrant workers from Thailand, whom Shinklovsky prefers over Palestinians. “Palestinian workers feel [a sense of] ownership [over the land] — maybe the land belonged to their grandmother. The Thai workers don’t feel like owners,” Shinklovsky says.

And yet, when he is in need of more laborers, Shinklovsky enlists the help of Palestinian contractors who bring workers from the West Bank. “We do it for profit, we are not philanthropists,” Shinklovsky explains, “but it is also important to capture territory. This is a national mission.”

The largest mass of agricultural land within the Green Line that’s been given to settlements have gone to those in the South Hebron Hills: 6,547 dunam [1,617 acres] were allocated to Ma’on, 7,450 dunam [1,840 acres] to Carmel, and no less than 21,043 dunam [5,200 acres] to Beit Yatir. For the sake of comparison, the kibbutzim Kiryat Anavim and Ramat Rachel, which received land on the coastal plain as “compensation” for not having enough agricultural land in the mountain area, received 3,200 and 2,300 dunam, respectively.

“The land we received is scattered throughout the Negev, land that none of the kibbutz and moshav movements wanted,” says Uri Zilberman of Gadash Hebron Hills. “We would have preferred land near our home, but the state decided otherwise.”

The land that was given to Gadash Hebron Hills is divided between orchards in the Arad Valley, the Dudaim trash site, Lev HaNegev, and Ofakim, as well as close to the Green Line where the wind turbines are to be built. The agricultural areas yield an estimated NIS 4 million a year — a considerable amount for relatively small settlements.

‘They get everything, we are nothing’

This story also has an ethnic and class dimension, which is playing out in a struggle between the generally wealthy South Hebron Hills settlements and Ofakim, a working-class Mizrahi “development town” in southern Israel. After the Ofakim municipality announced its plans to expand the city’s municipal boundaries eastward — in the direction of the settlements’ farms — the settlers launched an aggressive campaign against the decision.

Claiming that Ofakim’s expansion would lead to the “destruction of thousands of dunam of beautiful agricultural land that has been worked by Gadash Hebron Hills farmers for nearly 40 years,” they petitioned against the decision by Israel’s Committee for Preferred Housing Sites [commonly referred to by its Hebrew acronym, “Vatmal”] to approve the plan. That petition was ultimately rejected.

The settlements of the South Hebron Hills petitioned the High Court against Vatmal’s decision to expand Ofakim at the expense of the land they had received. The court accepted the petition in an interim order, although the expansion plan was later approved, much to the chagrin of the settlers. In August 2019, Bezalel Smotrich of the far-right Religious Zionism party, who was serving as transportation minister at the time, unsuccessfully opposed the construction of a road between Ofakim and Be’er Sheva that was required as part of the development of Ofakim’s new neighborhood, which includes 7,500 housing units east of the city.

In a letter to Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit, Ofakim mayor Yitzhak Danino claimed that Smotrich’s intervention against the road was “an election bribe, since it is clear that it was intended solely to benefit those farmers in the South Hebron Hills at the expense of Ofakim, completely ignoring their needs.” Smotrich responded with a Facebook post in which he said “the mayor’s violent, extravagant, and unbecoming style is mostly sad.”

“It was an ugly struggle against the [settler] farmers and the minister who tried to prevent the paving of the road,” Danino tells Local Call. “It’s a shame it happened that way. [The farmers] knew they were there temporarily. They should have said ‘thank you’ and evacuated the land.”

Zilberman tries to avoid talking about issues such as class and ethnicity. “Our disagreement is not with Ofakim,” he said. “We proposed an alternative that would lead to the same amount of apartments and open spaces for Ofakim on agricultural land that belongs just east of the city.” The disagreement, he says, is with the state, which “denies us contracts for the land and now dispossesses us after 33 years of working it.” Zilberman says they are currently in negotiations with the state over compensation for the plots near Ofakim.

Ofakim is not alone in its struggle against Gadash Hebron Hills. Another community adversely affected by the settlers’ land holdings within the Green Line is the unrecognized Bedouin village of Tel Arad in the Naqab/Negev, which borders the land given to the South Hebron Hills settlements.

Unlike their neighbors, the Bedouin residents of Tel Arad — who are citizens of Israel — are prevented from working in agriculture, and the areas around the village include little more than farm animals. Eid al-Nabari, a resident of the hamlet, says it wasn’t always so. In 1952, members of his tribe were loaded onto trucks and driven from their land to clear the way for what would eventually become the upper-class town of Omer, and quite literally tossed to Tel Arad. “When they arrived, they prepared the ground [for farming],” al-Nabari says of his predecessors.

According to a document submitted by representatives of the Bedouin residents to the Interior Ministry in 2018, until the 1970s, Tel Arad received around 30,000 dunam of land near Route 31 through a multi-year lease — which ostensibly includes the same areas currently cultivated by Gadash Hebron Hills. Since then, they have received seasonal leasing rights to only parts of the land, but even that has decreased in the last few years. In 2018, they asked the Interior Ministry for their own plots, like the ones designated for the nearby Jewish agricultural communities, but have yet to receive a response.

Today, al-Nabari says, Bedouin residents sometimes grow wheat and barley in the areas around the settlement, but as soon as inspectors from the Environmental Protection Ministry’s “Green Patrol” identify the crops, they come and plow the fields. Al-Nabari is not aware if the plots south of Tel Arad are cultivated by settlers, but the very fact that the settlers receive areas for cultivation, while the residents of Tel Arad do not, infuriates him. “They get water, they get everything, we are nothing,” he says. “My heart burns when I see the land.”

Zilberman says the settlers have a “complicated” relationship with their Bedouin neighbors. “On the one hand, there is Jewish activity, there are benefits to that. You can come to work when you need to. On the other hand, there are agricultural thefts and unruly conduct. I do not come to replace the state. Our Torah teaches us to love the [non-Jewish] stranger, but there are rules in this matter: the stranger needs to accept the authority of the state in which he lives.”

When I ask him whether he can understand why the Bedouin may feel discriminated against, he responds: “Your question is correct and embarrassing. But I have my own troubles. I am adversely affected more than the Bedouin. After 30 years, I am being thrown out of the land near Ofakim without any rights. We are fighting tooth and nail because we believe this is our country. We are not ashamed of it, but we are not looking to hurt anyone.”

The settlers profit, everyone else loses

Although the areas given to Gadash Hebron Hills in the Arad Valley are located in a kind of “bubble” surrounded by the city of Arad’s municipal area, the municipality does not benefit from the property taxes. In 2013, the Interior Ministry recommended transferring all these areas to Arad’s jurisdiction, which would allow it to tax Yatir Winery and other profitable business ventures in the area, bringing in a potential NIS 1-4 million a year for a municipality which, according to the Interior Ministry, is in dire straits. Yet this recommendation has not been implemented.

Instead, Gadash Hebron Hills and Yatir Winery pay property taxes to the Har Hebron Regional Council in the West Bank, where the settlements themselves are located. In other words, a local council beyond the Green Line receives money from property taxes on land inside the Green Line.

In order to regularize this arrangement, the Har Hebron Regional Council actually requested that its jurisdiction be expanded past the Green Line and into Israel. In a discussion held by the Interior Ministry’s Geographic Committee, which oversees and adjusts the jurisdictions of various towns in the area between Arad and the Green Line, the Har Hebron Regional Council proposed to expand its jurisdiction to include the moshavim of Har Amasa and Livne, which are partially beyond the Green Line, and even the towns of Yatir and Hiran, which are fully inside Israel.

Hiran is the Jewish town slated to be built on the ruins of Umm al-Hiran, a Bedouin village in the Naqab whose residents are to be forcibly expelled. In other words, instead of Israel annexing the settlements in the South Hebron Hills, as proposed in the Trump plan, the Har Hebron Regional Council is proposing to annex territories inside Israel to the West Bank.

The members of Gadash Hebron Hills, as well as the owners of Yatir Winery, are vehemently opposed to the idea of paying property taxes to Arad or any other regional council inside Israel, preferring to stay in an area not directly under the jurisdiction of any council.

Although the Interior Ministry believed the logical solution was to transfer the land in question to the Arad municipality, it ultimately decided to avoid doing so. “Gadash Hebron, Yatir Winery, and private farms [not owned by the settlements] will provide Arad with additional funds that will bring the city out of its difficult economic situation,” said the report, “but these payments will make it extremely difficult [financially] for Gadash Hebron Hills and Yatir Winery, and particularly the private farms in the area, and it is unclear that they will be able to meet these payments.” Like in the case of Ofakim, the lives of the South Hebron Hills settlers are prioritized over the 27,000 residents of Arad.

Zilberman says that it was not greed that brought them to adopt the wind turbine project, claiming the settlements have supported building them in the area since the early 1980s, when their profitability was questionable. He still does not know exactly how much the settlements will benefit from the wind farms, and says he does not know where the tens of millions of shekels per year comes from. The tariff for the electricity company has not yet been determined, nor has the cost of the land, turbines, and transportation.

Regardless of what transpires with regards to their jurisdiction, it is clear that the territories Israel has handed over to the settlements for ludicrous amounts — Beit Yatir reportedly paid a discounted price of NIS 250,000 for a lease until 2061 — will yield them millions of shekels a year. Moreover, argues Etkes, the data revealed here prove that Israel is willing to prioritize the profits of a minority of settlers not only over Palestinians in the occupied West Bank (“a well-known fact,” he notes), but also over other Israeli citizens.

“Beyond that,” Etkes adds, “it is clear that land allocations of this magnitude, especially in the Arad area, are intended to decrease the Bedouin population living in the northeastern Negev, and to create a buffer between this area and the South Hebron Hills, where there is a large Palestinian population.”

What these findings show, above all, is the depths to which the State of Israel had erased the Green Line many decades ago — and not only in the direction most commonly understood.

A version of this article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.