Redrawing the map of Jerusalem will not lock out potential attackers. Instead, it will only spark the sort of reaction one could expect following the wholesale nullification of rights from a significant number of Palestinians.

By Yoav Galai

With so much being written about the volatility of the status quo on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, a bigger picture of a deeply divided city breaking apart is becoming lost. On Sunday, Israel’s Channel 2 reported that the government is considering revoking the residency status of Palestinians in East Jerusalem who live beyond the separation barrier. Though this would potentially remove tens of thousands of Palestinians from the city, such a move is only possible today due to a series of actions taken by municipal and state authorities over years.

The checkerboard of East Jerusalem

East Jerusalem is the municipal area stretching around 28 villages annexed to Israel following the 1967 war. Within a few years, Israel began constructing Jewish settlements in East Jerusalem — part of the government’s official policy of treating Jerusalem as a “united city.” Today over half a million people live there, the majority of them (around 300,000 people) are Palestinian. Looking out, Jewish and Palestinian neighborhoods checker the eastern part of the city.

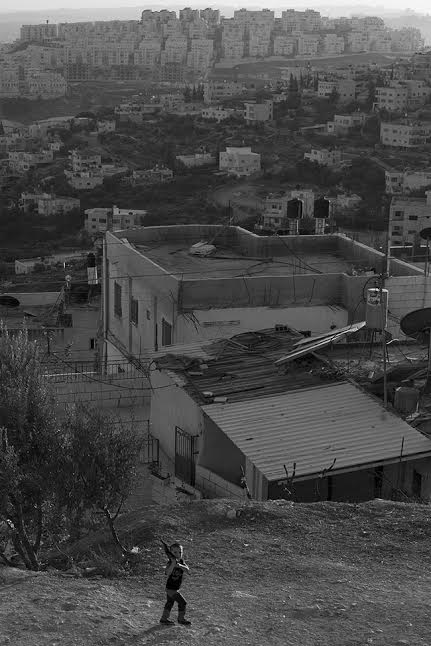

The picture below runs across the checkerboard, so to speak. It is taken from the direction of the Jewish neighborhood of Armon Hanatziv. In the foreground one can see the Palestinian neighborhood of Sur Baher. Behind it, the tall and orderly buildings on the hilltop is the settlement of Har Homa, and over in the distance are the West Bank cities of Bethlehem (right) and Beit Sahour (left):

While the Jewish neighborhoods of East Jerusalem enjoy all of the amenities a leafy suburb could expect, the Palestinian neighborhoods are in shambles. Garbage is often burned rather than collected; there is an acute lack of classrooms; the absence of approved city planning make construction mostly illegal, leading to frequent house demolitions; areas adjacent to Palestinian neighborhoods are declared “green areas” to prevent their expansion; and 84 percent of Palestinian children live below the poverty line.

To make things worse, since the turn of the millennium, several new Jewish settlements have been established in the heart of Palestinian neighborhoods. They have been the source of much tension, and according to an analysis by the Shin Bet, are the reason for a series of violent clashes that occured in 2012. The overall number of such settlers, however, does not exceed 3,000 people, and according to Israeli security expert Shaul Arieli, have “accomplished nothing but friction and escalation.”

The silent transfer

Palestinians in East Jerusalem mostly do not have an Israeli citizenship, but rather hold a status of “permanent residents.” Residents can vote in the local elections (which they mostly don’t) but not in the national elections. They cannot hold an Israeli passport, and in case they leave Israel for an indefinite amount of time — thereby failing to demonstrate that their “center of life” is in Israel — their residency status may be revoked. This has been the policy since 1995, and over the years, according to the Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI), nearly 15,000 people have had their residency revoked. Also, as many as 20,000 Palestinian residents that have moved away from Jerusalem to the neighboring West Bank, where they were able to find housing, have moved back to the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem since 2006.

The separation barrier was constructed during the Second Intifada, when suicide bombers from the West Bank blew themselves up in Israel. The barrier passes roughly along the Green Line, but due to what at the time seemed like logistical reasons, the barrier around Jerusalem often passes directly through neighborhoods, effectively locking out some Palestinians of their city. This is the case, for instance, in Kafer Aqeb, Dahiyat al-Salam, and Shuafat refugee camp, pictured below:

Beyond the wall

With construction nearly impossible in most of East Jerusalem, the neighborhoods beyond the wall — where police and building inspectors are seldom seen — also offered opportunity. As many as 100,000 Palestinians who hold Israeli residency status have moved there since the construction of the barrier. The next move had long been in the cards. Already in 2011 did Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat suggest redrawing the borders of the city along the lines of the separation barrier, dismissing the Palestinian majority of East Jerusalem in one fell swoop:

It is only with the recent bout of violence in Jerusalem that such dramatic policy has become viable. While the “division of Jerusalem” does not carry much political capital in Jewish-Israeli politics, the incremental cordoning off of neighborhoods at the edge of the city makes for an “elegant” solution to the problem of collective punishment. Of course, redrawing the map of Jerusalem will not lock out potential attackers. Instead, it would spark the sort of reaction one could expect following the wholesale nullification of rights from a significant portion of Palestinians in Israel, in what is essentially Israel’s largest Arab city.

Yoav Galai is a doctoral candidate at the School of International Relations at St. Andrews University in Scotland. He was previously a photojournalist based in Jerusalem. He tweets at @yoavgalai.

Related:

Israelis only understand force — and it makes them angrier, polls show

Let’s not forget that East Jerusalem Palestinians are stateless

Jerusalem: Between killing and crying