“Sledgehammer: How Breaking With the Past Brought Peace to the Middle East,” by David Friedman, Broadside Books, 2022.

David Friedman, the former U.S. ambassador to Israel, is a natural at baseball. He’s also a wise and empathetic manager of people; understands geopolitics better than State Department veterans; regularly delivers unanswerable ripostes and analyses in debates with his ideological opponents; and can, wearing his bankruptcy lawyer hat, save you a hell of a lot of money and legal trouble.

But not only that: his successful mission to bring peace to the Middle East is a story that evokes the prophets Isaiah and Micah. His historic interventions on Israel’s behalf bring to mind both the biblical heroine Esther, who prevented the destruction of her people by a Persian emperor and his viceroy, and Moses’ receipt of the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. Indeed, Friedman’s ambassadorial assignment reached a sanctity comparable to that of ascending to the altar in the ancient Jewish Temple in Jerusalem.

That, at least, is according to Friedman’s recent memoir, “Sledgehammer: How Breaking With the Past Brought Peace to the Middle East.” The book, which focuses on Friedman’s time as a Trump appointee, is published by HarperCollins’ conservative imprint Broadside Books, where Friedman’s stable-mates include New Right acolytes such as Dennis Prager, Dinesh D’Souza, Charlie Kirk, and Ben Shapiro.

In addition to the praise he lavishes on himself over the course of his 272-page book, Friedman includes plenty of examples of the plaudits heaped upon him by the powerful men he was surrounded by during those years. In his telling, his legal and political acuity, along with his grit, determination, and vision, were plain to almost all except for “Deep State” operatives, progressives, and phony pro-Israel Democrats who sought to foil him at every turn.

His labored self-aggrandizement aside, however, Friedman’s overarching theme, though not presented as such, is to narrate the accelerated expulsion, dispossession, and violent repression of Palestinians as an extended moment of American, Israeli, and Jewish self-actualization. And in that, “Sledgehammer” — both by omission and inclusion — says as much about the administration Friedman officially represented, and its still-unfolding legacy, as it does about the man himself.

A fantasy of hallucinatory proportions

It is clear from the get-go that “Sledgehammer” is not to be an honest accounting of Friedman’s time as ambassador. It has little need to be: his attitudes toward Israel, coupled with his assault on decades of U.S. diplomatic precedent in the region, have sufficient backing among the American-Jewish establishment such that Friedman has little to gain by writing anything other than an autohagiography.

By the same extension, what Friedman posits as the keystone of his personal and institutional legacy as ambassador — the Abraham Accords — has been accepted by much of the American-Jewish establishment as the miraculous bestowing of Middle East peace that “Sledgehammer” frames it as. Never mind, as numerous commentators have written on this site, that the “peace” struck between Israel and the UAE — followed by agreements with Bahrain, Sudan, Morocco, and Oman — is a fantasy of hallucinatory proportions. What matters to Friedman is the cruel myth that regional “peace” is attainable without regard for Palestinians, and without the need for Israel to face consequences for apartheid, occupation, ethnic cleansing, and its permissive attitude toward extrajudicial executions.

This marks one of the two core components of Friedman’s fantasia: the parallel and paradoxical erasure of, and glorification of Israel’s domination over, Palestinians. Here, Friedman’s hyperbolic recounting of his exploits in biblical terms take on their true significance: yes, the egotism and disconnection from reality they display are ripe for ridicule, but their absurdity does not diminish the callousness and violence inherent in casting racist repression as mythos.

That is precisely, without a shred of shame, what Friedman is doing here. His reference to Isaiah and Micah comes in his prologue, where he meditates on the need to make peace using a “sledgehammer” — the word “crush” is thrown around here too — and points to an infamous 2019 ceremony in which the ambassador swung an actual sledgehammer at a faux wall during an inauguration ceremony for a new tunnel beneath the Palestinian neighborhood of Silwan in Jerusalem, part of a long-running pet project by far-right settler groups in the area.

The various arms of that same project have been responsible for the forced expulsion of Palestinian families, dangerous structural fissures in the homes of others, and the rapid securitization of the area, bringing with it a blanket of CCTV cameras, armed private security, and a consistent police presence. All this, judging by Friedman’s description of the settlers’ interventions in East Jerusalem, is just and pre-ordained, with his own stagey performance representing a reverential response to peacemaking calls issued by the biblical prophets.

Similarly, Friedman likens the plaque on the newly-moved U.S. embassy in Jerusalem, which was unveiled during its 2018 opening ceremony, to a more famous pair of stone tablets. After a replica of the plaque he had sent to Trump was inadvertently broken, Friedman, in replacing it, told his boss that “if Moses had broken the first set of the Ten Commandments and then replaced them, we should do no less with the embassy plaque.” That was the embassy opening that took place on the same day Israel shot dead dozens of Palestinians marching to the Israel-Gaza fence, demanding an end to the siege and their right to return to their historic land. Friedman waves away the killings as a “bad look,” while complaining that the media only reported on the massacre because it occurred on the same day as the ceremony.

Meanwhile, Friedman’s invocation of Esther — one of the relatively few women who break through the relentless onslaught of men in the author’s anecdotes — caps off his retelling of the U.S. government’s recognition of Israel’s annexation of the occupied Golan Heights. As he listened to the reading of the Book of Esther the night of Trump’s declaration, Friedman was especially struck by the part in which Esther’s uncle, Mordechai, urges her to use her privileged status as the queen of Persia to intercede on her people’s behalf. “It was hard,” he muses, “not to see some similarities with my own extraordinary personal experience.” Esther, it will be recalled, managed to avert the genocide of her community. She also, at the end of the tale, assents to and appeals for revenge massacres against the Persians; Friedman, presumably, did not intend for this to be an explicit part of his analogy.

The mask slips off

Friedman’s gift-wrapping of anti-Palestinian violence in the language of Jewish salvation brings us to the second pillar of Friedman’s memoir: its effective summarizing of the malign impact of the Trump era on the American-Jewish establishment and on the resurgence of violent far-right antisemitism in the United States.

Here, too, Friedman has inserted silences into “Sledgehammer” around Trump’s anti-Jewish bigotry (which Friedman explicitly denies), along with that of his party and of far-right Evangelicals, the latter of whom are clearly a core part of Friedman’s intended audience for this book. (There are about as many quivering references to shared so-called Judeo-Christian heritage and values, and their underpinning of American values, as you would expect.)

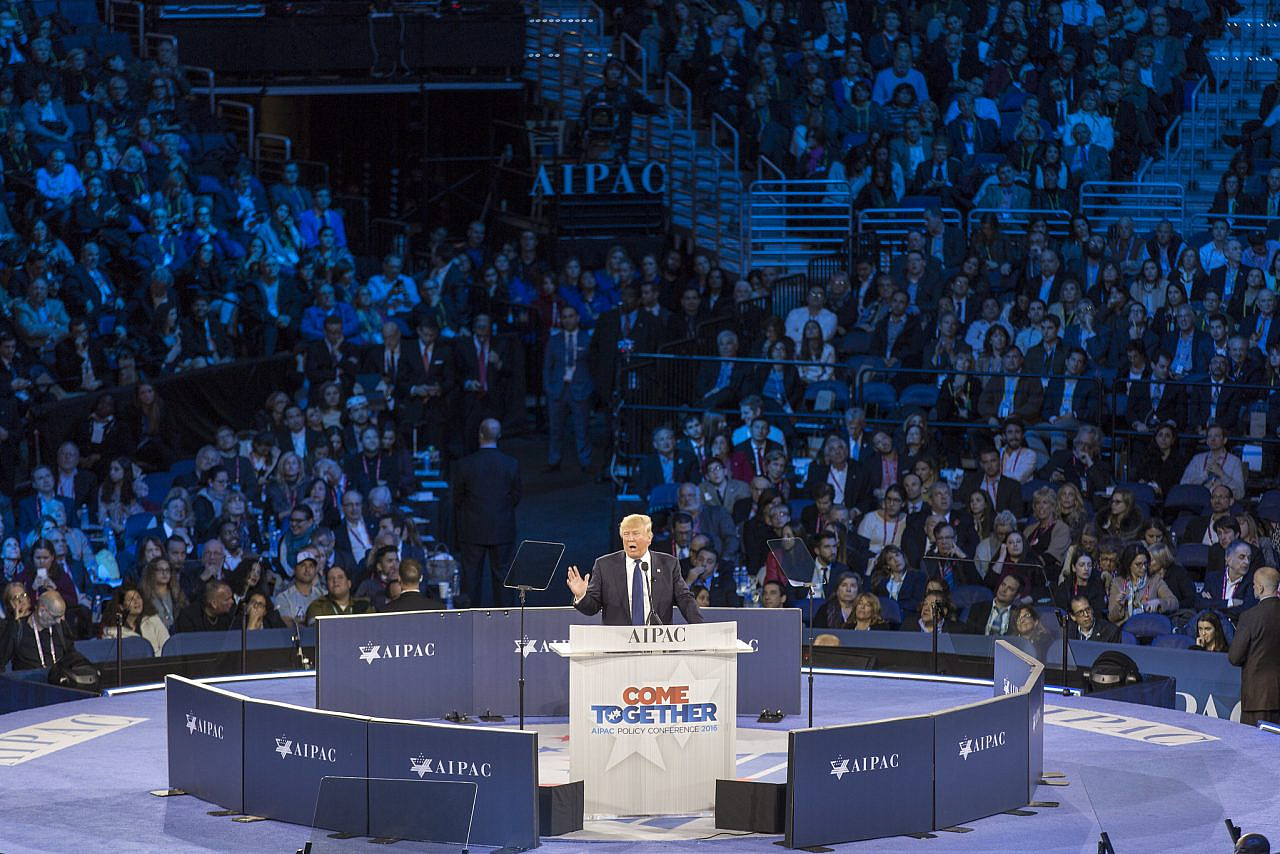

Yet for all that Friedman touts about the radicalism of his interventions, the truth is that the Trump years did not birth, even if they did further entrench, the ideological alignment around Israel between the more recognizable Jewish far right — like the Zionist Organization of America, the Republican Jewish Coalition, and various hasbara projects sponsored by ultra-conservative mega donors — and the self-identified bipartisan American-Jewish establishment, which includes AIPAC, the Anti-Defamation League, and the American Jewish Committee.

Indeed, the boundary between these groups and the American-Jewish far right on matters regarding Israel has been far blurrier than the more “centrist” organizations would like to admit. The much-vaunted, strenuously-defended American-Jewish “consensus” on Zionism and Israel, while not as immutable as these groups pretend, is nonetheless a powerful idea that the institutional community has long seen as its key strength. Such is the hold of this paradigm that some of the most high-profile and mainstream of these groups have consistently chosen to place it above other matters — say, their commitment to racial justice in the case of the ADL, or their commitment to democracy in the case of AIPAC.

There is no denying, however, that the mask, which had been slipping for some time, dropped fully during the Trump years.

The American-Jewish establishment openly embraced Trump’s policies on Israel despite their being delivered by an administration that at times was almost indistinguishable from a white nationalist crime syndicate. That self-sabotage was, in part, thanks to an ongoing myopia regarding the potential for the American state to threaten its Jewish population — a result of decades of the doctrine of American, and American-Jewish, exceptionalism.

But that embrace was also rooted in a long-running trend within the American-Jewish establishment itself — one the Trump era made so clear, and to which Friedman wholeheartedly contributes in his memoir: the contradictory impulse that support for Israel, touted as the solution to Jewish insecurity in the diaspora, reigns supreme even as one of the most politically powerful segments of that support, the Christian far right, is actively contributing to that insecurity. It was former ADL chief Nathan Perlmutter who wrote, 30 years ago, that the decision to overlook the antisemitism of Evangelical eschatology because of Christian Zionist support for Israel could be revisited “[i]f the Messiah comes… Meanwhile, let’s praise the Lord and pass the ammunition.”

Perlmutter’s take resounds in the present day. Yet the Republican Party’s mainstreaming of 1930s-style antisemitism makes today’s equivocation a very different, and much more dangerous, prospect. Far-right evangelicals may have had the ear of the Reagan administration, but the GOP at the time was not consistently spreading and campaigning on antisemitic conspiracy theories, striding onto the floor of Congress clutching a copy of “Mein Kampf,” or publishing campaign flyers showing Jewish Democratic opponents with digitally-enlarged noses or gleefully grasping money. None of this, of course, made it into the pages of Friedman’s memoir.

What “Sledgehammer” reminds us of, then, is not so much the existence of whitewashing and distortion of antisemitism in service of a putative pro-Israel coalition, but more the capacity of that distortion to expand and adapt in response to changing norms in both Israeli politics and the American discourse on Israel-Palestine.

It should be acknowledged that parts of the American-Jewish establishment that rallied around Friedman’s diplomatic “achievements” do not share his apparent assessment that modern antisemitism is purely a disease of the left, and right-wing antisemitism no more than a historical artifact. Yet it is clear that there has been a steady coalescence around the idea that antisemitism on the left — whether actual antisemitism or not — is as much of a threat, if not more so, as that on the right.

This belief wholly relies on the sweeping up of anti-Zionism, BDS, criticism of Israel, and the very expression of Palestinian identity into a seething mass of anti-Jewish praxis that ostensibly warrants greater mobilization than do actual far-right massacres. Whether they are aware of it or not, that is where the anti-Palestinianness and anti-Jewishness of Friedman’s worldview and that of his peers converge.

It is in this same framework that so much of the American-Jewish establishment has continued to invest, despite the role of their bedfellows in the physical and spiritual wreckage of the Trump years. Indeed, there was a sad predictability to the sight of ADL CEO Jonathan Greenblatt declaring in May that anti-Zionist groups are “the photo inverse of the extreme right the ADL has long tracked.” It’s a line that could have been plucked straight from Friedman’s memoir, had the latter contained even a single mention of the modern-day far right.

An indelible mark

It would be gratifying to dismiss “Sledgehammer” as the story of a parallel reality of the Jewish far right’s making: a fantasyland in which Palestinians at once do and don’t exist, and are not to be discussed or understood outside the context of terrorism or — for the purposes of hasbara — bad faith claims of coexistence. It is a reality in which progressive universalism is anti-Jewish, anti-American, and anti-Israel, and in which a penchant for caricatures and conspiracy theories that wouldn’t look out of place in Der Sturmer or The Protocols of the Elders of Zion can largely be overlooked — as long as the perpetrator has expressed their admiration for Israel and its apartheid regime.

But the problem with doing so, as made clear by Friedman’s multiple “wins” during his ambassadorial tenure, is that this alternative reality does not just exist within the minds of the far right. It is rapidly being translated into a legal and political architecture that effectively mires this vision into place, with aggressive waves of legislation in the United States, Israel-Palestine, and beyond that criminalize everything from boycotting Israeli settlements, to commemorating the Nakba, to memorializing Palestinians slain by Israel — often under the banner of combating antisemitism.

None of these measures, of course, will actually succeed in snuffing out the movement for Palestinian rights and justice. Neither will they prevent white supremacists from shooting up synagogues, which should surely be the top priority of any policies that purport to tackle antisemitism. But they are, by design, making it harder to effectively name and mobilize against both Israeli oppression and anti-Jewish hatred.

Fortunately, the remarkable momentum of Palestinian grassroots organizing in the United States, and the accompanying shifts in the attitudes of young American Jews toward Israel, serve as powerful countervailing forces that are bringing public opinion — at least among Democrats — along with them. Even with the gains of this movement, however, there remains a long political and cultural fight ahead, one on which Friedman has — even if not to the biblical dimensions he claims — undoubtedly left his mark.