Given the accelerating normalization of religious far-right ideology in Israel in recent years, it is not surprising that filmmakers are looking to the history of right-wing fanaticism to try and figure out how Israeli politics inherited its current trends. Four films on the topic have come out in as many years: “Incitement,” which takes a trip to the inner world of Yigal Amir, the man who assassinated Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin; “The Prophet,” which charts Rabbi Meir Kahane’s career as he takes his message of righteous Jewish violence from the streets of New York to the halls of the Knesset; “The Settlers,” which tells the history of the settlement movement; and “The Jewish Underground,” about the terrorist group of the same name.

“Incitement,” directed by Yaron Zilberman, is a painstaking recreation of the atmosphere of the Oslo era. It focuses above all on the Jewish Israelis who were mobilizing in opposition to the talks and, more ominously, to Rabin. The camera lingers on anti-Rabin imagery at the Bar-Ilan University campus, in public squares, and in the streets: graffiti inciting against the prime minister; wanted-style posters calling him “The Murderer” with a target on his head; and placards at furious demonstrations showing him wearing either a keffiyeh or an SS uniform.

We also see Amir attending the funeral of Baruch Goldstein, who shot dead 29 Palestinians in Hebron’s Ibrahimi Mosque in February 1994. There, he hears a rabbi discussing the applicability of a religious death warrant against Rabin, on the premise that the prime minister endangered Jews by negotiating for territorial compromise. Amir is privy to other similar discussions in the early stages of the film. From here, we are led to assume, it was a short step for him to decide that he would be the one to fulfill that death sentence.

There are other moments of foreshadowing. Early on, Amir’s mother tells a female romantic interest he invites home that his first name, Yigal, means “He will redeem,” and that she is convinced he will redeem “his people.” Her child, she says, is destined for greatness — a message she repeats to Amir when his would-be girlfriend rejects him. In another family scene, one of the film’s most powerful, Amir’s father, catching wind of his son’s plans, shouts at him: “It will take generations — generations! — to heal such a wound.”

“Incitement” also addresses Amir’s background as the child of Yemeni immigrants to Israel. A knotted set of tensions plays out in his household: his mother’s disdain for the racist elitism of Ashkenazi Israelis; the arguments between her, a hawk, and his father, who has more hope for the Oslo Accords; the evident discomfort of Amir’s Ashkenazi friend when she arrives and sees a family gathering is in the works, a nod to Amir’s marginalization within Israeli society as a Mizrahi Jew.

Yet the film makes little of this dynamic within the religious-Zionist world. Here, the rabbis inciting against Rabin are invariably Ashkenazi. In the real world, in the wake of the assassination, parts of the religious-Zionist establishment sought to absolve themselves of responsibility for the murder by pointing to Amir’s Mizrahiness as evidence of his outsider status.

The fact that we know how the story ends does nothing to alleviate the tension in the film. Rather, the movie is haunted by the looming disaster from the first frame. The splicing of archival newsreel footage into the proceedings heightens the sense of foreboding, not least during the film’s final moments, when we see grainy, real-life footage of Amir waiting by Rabin’s car — conspicuous in his blue t-shirt — interspersed with filmed close-ups of him talking amicably with Rabin’s security detail. He is, they believe, one of them.

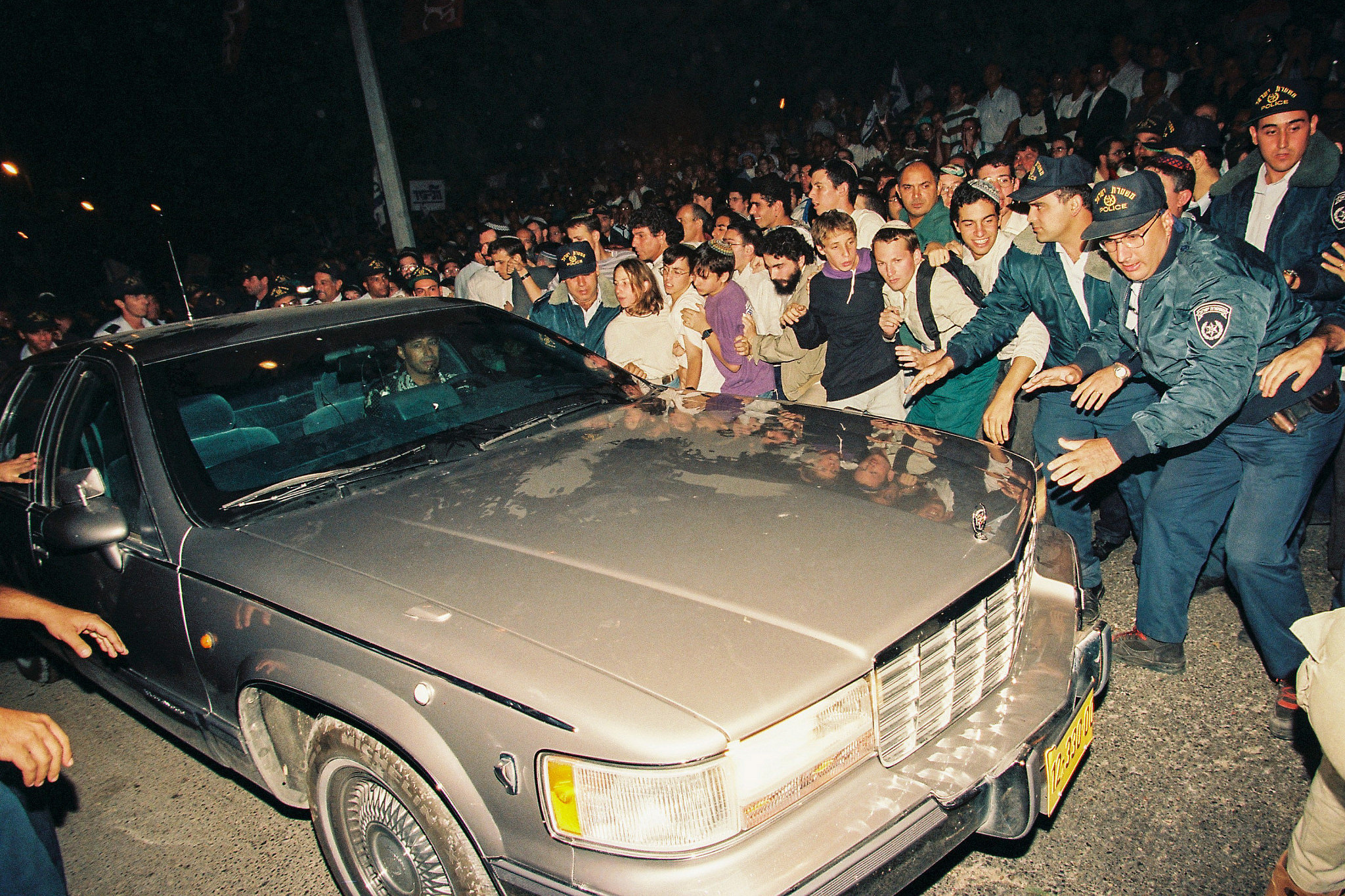

Like several other recent Israeli films, “Incitement” plainly nods to the fact that extremism has taken root at the very top of Israeli politics, embodied in the figure of Benjamin Netanyahu and in the gaggle of religious-Zionist rabbis who put a doctrinal bounty on Rabin’s head. Zilberman cuts in footage of Netanyahu’s presence at splenetic anti-Rabin protests before the assassination, including his infamous appearance on a balcony overlooking Jerusalem’s Zion Square, as screaming right-wing Israelis call for Rabin’s death.

Zilberman is right to make this connection, but given this is a film about extreme religious nationalism, and given the political moment in which his work is being released, it feels like a missed opportunity. The film avoids interrogating the deeper ties between the religious-Zionist and political elites in Israel. Even more remiss is the fact that the movie draws back from examining why Netanyahu has been so successful — and why, just a few months after helping to incite Rabin’s murder, he was elected as the head of the next Israeli government.

This omission partly lies with the almost complete absence of Palestinians from the film. It is true that “Incitement” is a story about the ethnically-segregated world of the Israeli religious right, and the unexamined frenzy into which it whipped itself over the Oslo Accords. But the film is intended as a deep dive into the ideology of that same group, and how revealing can such a project be if it fails to engage with that ideology’s object of fear and hatred? Rabin is indeed the main target of the film’s protagonists, but only inasmuch as Amir and his peers believed him to be a stooge of the Palestinians, and thus a mortal threat to the Jewish State.

With this gap, the film perhaps said more about the current moment than it intended to: “Incitement” arrived in U.S. cinemas within days of U.S. President Donald Trump revealing his “Deal of the Century,” a roadmap to annexation that constructed detailed plans for a Palestinian future without consulting anyone who would have to live in it. In the film, as in Trump’s plan, Palestinians are absent presentees.

The Israeli far right is also under the microscope in “The Prophet,” from director Ilan Rubin Fields. The 2019 documentary explores the career of the Brooklyn-born extremist rabbi Meir Kahane, who founded the Jewish Defense League in New York in the 1960s, and served in the Israeli parliament in the 1980s as the sole representative of his Kach party. It revisits some of Kahane and the JDL’s most notorious acts, from the 1970 bombing of the Aeroflot offices in New York, to Kach’s proposal to open an “emigration office” in the northern Palestinian city of Umm al-Fahm, in order to try and encourage Palestinian citizens to leave the country.

Along the way, Fields interviews members of Otmza Yehudit, the Kahanist party that ran throughout the triple round of Israeli elections over the past year, and whose leaders are all former acolytes of Kahane. Baruch Marzel, commenting on Kahane’s proposals to expel Palestinians from the entirety of the biblical “Land of Israel,” notes that his mentor “pointed out an inherent contradiction between the Jewish state and democracy.” Any other option is a fantasy, Marzel says: “It’s either democratic or Jewish. It can’t be both.” Such a mindset, shoots back legal expert Moshe Negbi, affirms the UN’s 1975 declaration that Zionism is racism.

This exchange — conducted via talking head interviews, rather than dialogue — hits at one of the film’s two shortcomings. It seems to look directly in the eye the contradictions between having a particularistic ethnic state and a democracy, and then looks away again, dismissing it as simply an unassimilable idea voiced by extremists.

This is a pity, because Fields’ film goes further than “Incitement” in pointing out how systemic racism and chauvinism are in Israeli society and politics. Toward the end of the film, he moves through a series of Jewish terror attacks — the Goldstein massacre, the murder of Muhammad Abu Khdeir, the firebombing of the Dawabshe home in Douma — and then deftly switches to the Knesset, showing Likud politicians defaming Palestinians, before ending with the passage of the Jewish Nation-State Law. The final frames of the film show scenes from Israel’s Independence Day, a festival of flags and fireworks.

The implicit message here is clear: a structural ill has taken root in the State of Israel. And in 2020, when the Likud party, which has ruled the country for more than 30 years, has repeatedly offered support to Otzma Yehudit and made efforts to win over its voters, Fields’ framing rings true. But the arc of the documentary, and its avoidance of pre-Kahane history, leaves the impression that a single racist demagogue set the rot in motion, rather than that he exposed and exploited deep-set xenophobia and racist paranoia that has been part of the state’s character from day one.

The documentary’s other major oversight is its failure to interview even one woman, or a single Palestinian. (A woman is featured as an interviewee in archival footage Rubin includes in the film.) Given how central issues of ethnic purity and gender (and the connections between them) are to Kahanist ideology — and Israeli far-right ideology in general — this is a striking pair of omissions. It essentially leaves the story to be told only by those at its very center, who are almost exclusively Ashkenazi men, and effaces the voices of those on the margins of the far right, and of its victims.

Of the four films, “The Jewish Underground” is perhaps the most successful at demonstrating that acquiescence to violent right-wing radicals is a feature, and not a bug, of the Israeli political system. It, too, however, stumbles in the gender parity of its interviewees: the first hour fails to include any women as a subject. Tellingly, the only appearance of a woman during this time is in the background of an interview with one of the group’s leaders; she is a blurry figure, with her back turned to us, standing in the kitchen.

Nonetheless, each of these four films manages, in some way, to exceptionalize its subjects. They all focus on groups or individuals who are in some way understood as being outside the Israeli mainstream, and thus present them as aberrations from, rather than products of, Israeli society. Even with the warts-and-all exposés of these men’s violent, chauvinist worldview, this approach cleaves to how these figures are addressed in the wider Israeli conversation: as bogeymen, who wait in the wings and then explode onto the scene in order to try and ruin Israel for everyone.

By holding up the likes of Kahane, Amir, and the Jewish Underground as examples, without seriously addressing the ideological and historical roots of their politics — forever starting the clock in 1967, and not in 1948 — these films stop short of being the clear-eyed reckoning they strive to be. In that sense, they reflect the present-day singular focus on Netanyahu as the source of anti-democratic trends in Israeli society, with little-to-no engagement with what Israeli “democracy” comprised before he came to power.

It is all well and good to look at Kahane and his followers yelling “Arabs out;” to look at Miri Regev standing at the Knesset podium and telling Balad MK Haneen Zoabi, “Go back to Gaza, traitor;” to look at protesting MKs from the Palestinian-led Joint List party being ejected from the Knesset plenary hall as their colleagues pass the Jewish Nation-State Law. But without acknowledging that the state has, in one way or another, been saying “Arabs out!” since 1948, filmmakers, and observers in general, will never get to the bottom of who these “bogeymen” are — nor push back on the havoc they wreak.