This article originally appeared in “The Landline,” +972’s weekly newsletter. Subscribe here.

Last week, we witnessed the deaths of 33 Palestinians in Gaza by an unprovoked Israeli murder campaign — or as they named it, “Operation Shield and Arrow.” The assault on Gaza not only coincided with the 75th anniversary of the Nakba, but also underscored the fact that the brutality with which Israel ethnically cleansed some three-quarters of a million Palestinians in 1948 continues to this day.

Palestinians around the world took to the streets not only to protest their governments’ complicity in the latest Israeli massacre, but also to have a space to express their grief and mourn 75 years of violent colonization, apartheid, and displacement. Given that Israel continues to prevent the return of millions of refugees and their descendants, remembering the Nakba is foundational to a Palestinian identity centered around our yearning to be back in our homeland.

Yet in countries like Germany, which is home to thousands of Palestinians, our right to freedom of expression and assembly is dangerously under attack. For the second year in a row, the Berlin police preemptively banned all Nakba commemorations and demonstrations, surpassing the upswing in violent policing tactics being reported elsewhere in Western Europe, including the U.K. The ban was implemented on the basis that the Nakba Day events posed an “immediate danger” of antisemitism and the glorification of violence.

Last year, Berlin police arrested and detained 170 people, including some who did not even participate in a demonstration; in a recent court hearing, a police officer admitted that they targeted people for wearing the keffiyeh, being dressed in the colors of the Palestinian flag, or simply looking like they intended to join a rally.

Following this year’s ban, the only event allowed to take place was a purely cultural one at Berlin’s Hermannplatz last Saturday. But even this was authorized with heavy conditions: police banned all speeches, took down signs at stands that included the words “BDS” or “Nakba,” confiscated political pamphlets, and at one point even told organizers that dabke, the traditional Palestinian dance, was “too political.” Surrounded by dozens of police officers who continuously videotaped the event, Berlin succeeded in making Palestinians feel the chilling effect of full-blown repression.

In the name of tackling “Israel-related antisemitism,” German authorities are doing Israel’s bidding in their own country. Now, however, it seems they are also keen on mimicking Israel’s repressive tactics against all expressions of Palestinian identity. Earlier this year, Israel’s far-right National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir ordered the Israeli police to enforce a ban on the Palestinian flag in public spaces, claiming that the flag is a rallying symbol for “terrorists.” And just last Saturday, the Berlin police banned a gathering that ironically was centered around the historical banning of the Palestinian flag, organized by Palestinian, Jewish, and German women.

With Israel’s encouragement, Germany’s adoption of the stifling IHRA definition of antisemitism and the Bundestag’s passing of the anti-BDS resolution has opened the floodgates to a new wave of repression against all aspects of Palestinian identity, bringing the ongoing Nakba to Europe.

I am the granddaughter of Palestinian refugees who were violently expelled from our ancestral village of Jimzu in the center of historic Palestine. Dispersed all over the world and becoming refugees within Palestine, my family still instilled in me a remembrance of our past and a yearning for our eventual return.

July 9, 1948, the date on which the Yiftach Brigade of the Zionist paramilitary group the Palmach invaded Jimzu, was the beginning of a lifetime of perseverance and resistance for my family and eventually me. Yet I am only one of thousands of Palestinians in Germany with identical stories, all living in a country that values the supreme power of a foreign state over its own citizens and residents.

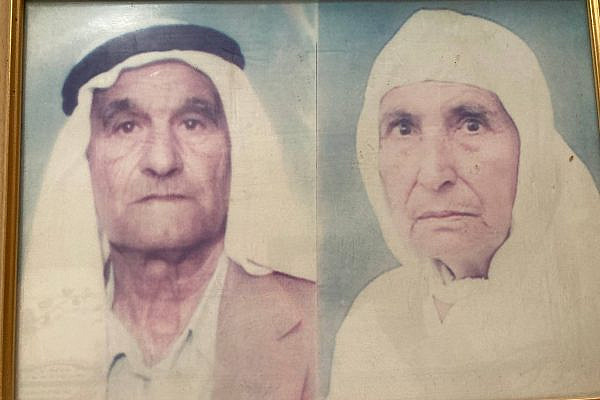

“We want to die in our homes in Palestine,” my great grandfather, the mukhtar of the Aqabat Jaber refugee camp in Jericho, said in the documentary, “Aqabat Jaber — Peace with No Return?” “Who doesn’t want to live in peace?” he continued. “But there can be no peace without our right to return home. It will take years, it won’t happen now — it will take time, but we’re only here temporarily.”