Even Nakba Day, which falls on May 15, is somehow dependent on the Zionist narrative. The date etched into the collective memory of Palestinians as the start of our national catastrophe marks the morning after David Ben-Gurion’s declaration of the establishment of the nation-state of the Jewish people, and the beginning of the withdrawal of British troops from Palestine.

But the events of the “actual” Nakba began well before that day, as historians like Adel Manna and others show, such as with the massacre at the village of Balad al-Sheikh, near Haifa, in December 1947, a few days after the United Nations approved the partition of Palestine.

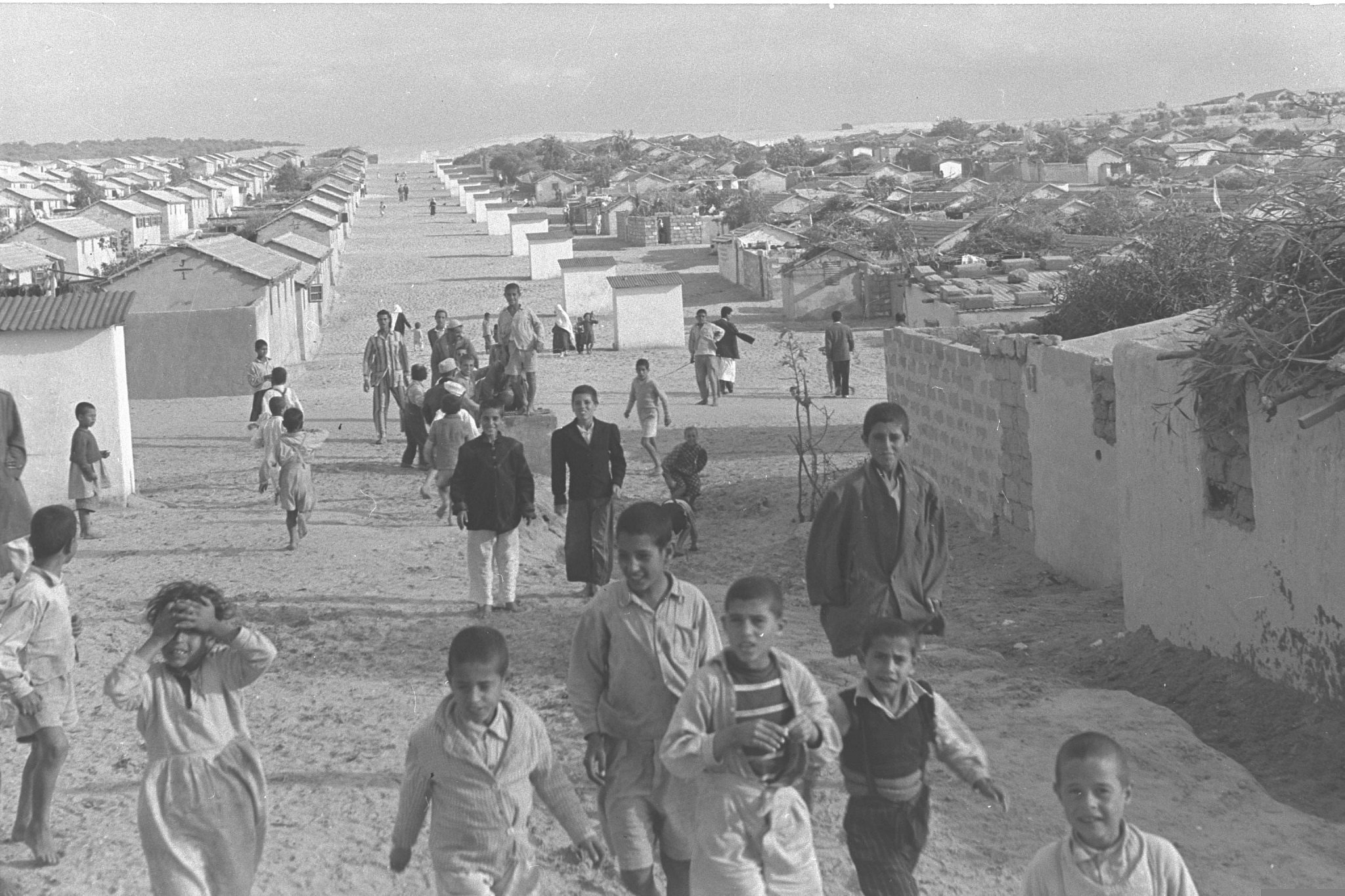

The vast majority of Palestinian villages situated along the coastal Mediterranean plain were completely destroyed in those days, with only Jisr al-Zarqa and Fureidis surviving. In the northern region of Safed, only four out of 74 villages remained after the Nakba. In a recent interview on al-Shams radio station, Manna argued that Arab life in the north — Galilee, Nazareth, and the surrounding villages — survived because the UN Partition Plan designated them as part of the future Arab state, and so Zionist forces did not prioritize their capture.

Regardless of the starting date, there is consensus that the events of the Nakba constitute the most significant period in Palestinian history, and that collective memory of the Nakba is the glue that binds together Palestinians all over the world.

Though we have been reckoning with its history for years, including by restoring and documenting the stories of the displaced and the exiled, we are still far from uncovering the truth in its entirety. Every day a new horror is discovered. As we do so, the Israeli soldiers — now nearing the end of their lives — are finally starting to talk, corroborating the oral history of tens of thousands of Palestinians.

Before this documentation, a second and third generation of Palestinians were born into the Nakba — my generation, who came after 1948, the children of the internally displaced and the refugees. Many of us heard, day and night, what happened to our parents; others had to burrow through papers and memories on their own to assemble the alternative narrative, the one we didn’t learn in the history books approved by the Israeli Education Ministry. How did the Nakba affect us? What does it mean to grow up in its shadow? Is there something unique about us, as children of refugees living in their own homeland?

‘They are reproducing patterns from their parents’

I asked friends from various social circles about growing up as the second generation of the Nakba. One common answer, and one that resonates with me personally, is captured by Fatima Abbas: “There’s this phrase that my mother says: ‘failure is not an option.’ It doesn’t matter what your physical or emotional state is, whether you want to do it or not. We must study and succeed at any cost, to excel no matter what. Your diploma is your most powerful weapon.”

Abbas explained further: “I have six siblings. Three of them are teachers, one is a lawyer, one is a gynecologist, and I am a social worker. None of this could have happened without my mother, an extremely intelligent woman, pushing us. But she herself never finished her studies because of what happened in 1948.”

Abbas’s situation is not unique; in fact, I know it well from my own home. I am a double refugee — my mother is from Kufr Sabt and my father from Sajara, both depopulated villages, who married and raised five children, all of whom grew up with severe refugee syndrome. Success stories of the children of refugees, especially those in academia and well-respected professions like medicine, are a feverish obsession in Arab society, and a source of jokes at family events.

This phenomenon has a negative side , though: there is often intense pressure from our parents, and a need to ignore mental anguish and any weakness in favor of achievement at any cost. Abbas said that, as a result of this pressure, “we developed a powerful mental immunity to it, a sense of independence and endurance. When my mother compares anything to the hunger of being a refugee, and to the bitter cold of living in a tent, everything we have now is a luxury, if only because we have a roof over our heads.”

Dr. Adnan Abu Al-Hija, a clinical psychologist and lecturer at the University of Haifa, has studied the intergenerational trauma caused by the Nakba among the second generation of survivors and refugees. According to him, what Abbas calls “mental immunity and toughness” can exact a heavy mental toll on children whose parents are refugees.

“From my patients,” Abu al-Hija said, “I started to understand how the children of refugees are impacted, directly and indirectly, by their parents’ trauma, how they reproduce it and reflect it in their lives, in every way imaginable.” He notes that even the children’s choice of profession is affected by that trauma — such as choosing something therapeutic or cathartic.

This is why if parents deploy silence as a defense mechanism — a common phenomenon in which victims of trauma simply say that what happened happened, and that we don’t speak about it in the house — “Children in this situation are likely to grow up with emotional detachment and have social and communication issues, the roots of which lie in the traumatic but unspoken experience of their parents, all of which can harm their development,” he said.

“I have found that children of the Nakba have trouble connecting with others and struggle to feel a sense of belonging to a place,” he continued. “They find themselves jumping from place to place, physically and emotionally. It takes time to understand that they are reproducing patterns from their parents, who lost their homes, their families, and the stability of their lives. It affects your sense of your own security and safety in the world. A pessimistic worldview, anxiety, and other mental health issues are common among children who grew up with parents who went through the Nakba.”

For example, Abu al-Hija said, “I treated a pregnant woman who was suffering from terrible anxiety during her pregnancy, with no physiological explanation. The medical staff had no idea what to do. In the treatment session with her, I learned that her mother was forcibly displaced, while pregnant and with a young baby, and as she was escaping from fire and searching for shelter, she started to have contractions, and she eventually gave birth to a child who died young. My patient had heard this story countless times throughout her childhood, and she had clearly experienced intergenerational trauma.”

‘A massive cloud that hung over my generation’

Abu Al-Hija’s words made me think about how this may have affected my own life. It threw me back to a terrible experience, when we went with my mother to visit her uprooted village, Kufr Sabt. She told me and my siblings that the kids at her school in Nazareth called her the “tent girl,” because she was born in a tent as her family moved from shelter to shelter, before finding a house in Nazareth. My mother stood there, by the ruins of her home, and wept. It was the first time my siblings and I saw her in such anguish, crying in public. We took these facts in, but we never spoke about our mother’s trauma.

Maha Alnaqib, a lawyer and social-political activist from Lydd (Lod), said that her father found himself, at the age of 13, responsible for his family’s income after his own father disappeared with other refugees. Her father worked for four years to feed his blind mother and his brother, who stayed in Lydd after it was occupied during Operation Danny. “The most vivid thing that I got from my parents’ memory is their relationship to food, and my father’s shouting about anything connected to food,” said Alnaqib. “He would say, ‘You have to appreciate what you have, to watch over it, not to waste it, and to eat every last bite. You have no idea what hunger really is.’

“My father had PTSD — now that is clear to me,” she continued. “But as kids, my sister and I didn’t understand why he would become so angry when, for example, my sister said she didn’t like olive oil in her food. It was a law in our house: food was the holiest of holies.”

Most read on +972

Food is a recurrent theme among children of Nakba survivors. One young man wrote to me that his father forbade his mother from cooking certain foods — anything he ate as a boy in the refugee camp before they found him a permanent home. These included lentil stew, or raw dough meant to fill him up for hours that he was forced to eat, or mushrooms that he picked in the fields by the camp, which he found disgusting and which his grandmother called “the poor man’s meat.” “I ate stuffed mushrooms with cream sauce for the first time after I graduated college in Tel Aviv,” the young man wrote, “but I wouldn’t dare tell my father.”

A Facebook friend wrote to me that at her house, it was forbidden to bring figs or prickly pears inside, because those were the only foods her father could eat in the fields, where he stayed in July of 1948. “Until his last day, my father never brought these two fruits into his home.”

For other survivors, traumas were centered around the people that had been ripped from them by the Nakba. Nizar Hawari, from Tarshiha, said that her childhood was consumed by her parents’ search for their extended family, trying to collect any bit of information about them from refugee camps in Lebanon, Syria, and other countries.

“It constantly occupied them and us, like a massive cloud that hung over the children of my generation,” said Hawari. “It was our collective anguish. The stories of loss were always just around the corner, at every family or community event; the loss of this social anchor larger than yourself. The feeling that something is constantly missing.”

Hawari is describing what we all experienced as kids of refugees, an imaginary world prompted by the thought: “What if there had never been a Nakba?” It’s a conversation starter every family has used at some point. You end up either laughing or weeping, mourning what could have been.

One person who wrote to me on Facebook chose to look at the positive side of our experience as children of refugees: “Our parents lost their assets, their land, their homes, and their money, and they started from scratch, and it was really difficult for them. But, on the other hand, all of our achievements, which we got only through blood, sweat, and tears, belong to us and only us.”

They continued: “No matter how hard it is, we will emerge stronger and more successful than anyone who was never kicked out of their homes. Yes, refugee families are smaller, because a big part of the family isn’t here, and so there’s little support. But I feel so much closeness and unity and love for the ones who are still here. And that’s all there is.”

This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.