Amid the zeitgeist of diplomatic rapprochement and normalization in the Middle East — which has recently seen Saudi Arabia and Iran mend ties and Syria’s Bashar al-Assad welcomed at this month’s Arab League summit — the Palestinian Islamist movement Hamas took a step forward to repair its own regional relationships.

In mid-April, a delegation of senior Hamas officials, led by Ismail Haniyeh and Khaled Meshaal, traveled to Saudi Arabia under the guise of a religious pilgrimage. Yet being the first visit of its kind in more than a decade in which ties between Hamas and Riyadh had been unraveling, the political significance was unmistakable.

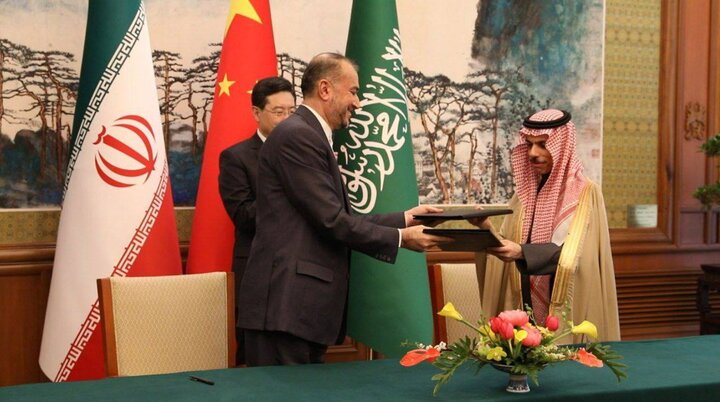

Some analysts framed the visit as a product of the breakthrough diplomatic agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia, which was brokered by Beijing in March. That, however, may be overstated given that there have been a string of similar gestures in recent years, such as Meshaal’s 2021 television interview on the Saudi network Al-Arabiya and the release of Hamas-affiliated political prisoners jailed by the Saudi government.

Nonetheless, the new atmosphere generated by the Saudi-Iran accord certainly offers a more conducive environment for Hamas-Saudi reconciliation. Moreover, the visit raises important questions about the impact of the Saudi-Iran rapprochement on Palestinians more broadly, especially given that the United States and Israel have made major efforts to bring Riyadh on board the Abraham Accords — the normalization project initiated by the Trump administration in 2020 and carried on by President Joe Biden ever since.

Although the recent rapprochement does not have direct implications for the Palestinians vis-à-vis Israel, it could ease some of the pressure that has mounted in recent years by ending the period of regional polarization and reversing the momentum of the Abraham Accords. The question is: will the Palestinian political leaderships take advantage of this moment?

Balancing acts

Lacking a state of their own, the Palestinians have always been highly dependent on the regional environment and reliant on external backing for their political cause. As such, the Palestinian liberation movement has, for decades, been forced to carefully navigate the Middle East’s complex politics and avoid antagonizing possible sources of support and hostility. Sometimes, however, the regional environment is so fraught that it makes this impossible.

Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 was such a moment. Caught between two important backers of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) which also hosted sizable Palestinian communities, Chairman Yasser Arafat found himself in an unenviable decision-making position.

Arafat ultimately tried to strike a sort of balance, opposing the U.S.-led military invasion of Iraq in favor of a regional diplomatic effort — an equivocal stance that was read by the PLO’s Gulf allies as a betrayal, given Kuwait was a clear victim of Iraqi aggression. The cost for the Palestinian community in Kuwait, and Palestinian politics more broadly, was catastrophic, as hundreds of thousands were forced to leave the country and the PLO experienced the worst diplomatic alienation in its history.

The 2011 Arab uprisings and the ensuing regional competition between rival ideological camps was another instance in which uninvolved political actors were pressured to choose sides. That is particularly true of the bitter hostility between the Saudi-Emirati alliance and Iran, which divided the Middle East and North Africa (as well as other regions like the Horn of Africa) in a localized cold war that exacerbated conflicts in multiple countries such as Syria, Iraq, Libya and Yemen.

With Tehran providing support to the Syrian regime and several substate actors and the Saudi-Emirati bloc moving into closer alignment with Israel, the balance for Palestinian groups like Hamas became untenable, and their regional relationships suffered. Even Hamas’s relations with Tehran were initially unsettled after the Palestinian group chose not to support the Iran-backed Assad regime against the Syrian opposition. Eventually, Iran’s financial backing and military support to Hamas resumed.

The decision by Saudi Arabia to restore diplomatic relations with Iran is important in this regard for two reasons. First, it reduces the violent polarization and competition in the region. While that is far likelier to be felt in places like Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Lebanon, it does take the pressure off of Palestinians as well.

This is meaningful both for the Palestinian political leaders who were forced into uncomfortable positions that threatened their material support, and for the Palestinian communities living in Arab countries that often bear the brunt of those decisions — as witnessed in Kuwait after 1990 and Syria after 2011.

The reduced tensions also free regional powers from having to choose sides among the rival Palestinian factions. It was therefore unsurprising to see Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas hosted in Saudi Arabia at the same time that the Hamas officials were in the country, as Riyadh intended to make a show of balancing its relationships.

Furthermore, the Beijing-brokered Saudi-Iran accord is a clear sign that Riyadh and its allies are acting more independently of their longstanding partnership with Washington. This current period of multipolarity and middle-power assertiveness could be beneficial for Palestinians; U.S. hegemony in the Middle East has clearly not served Palestinian interests well, and a shakeup in the regional order could provide new opportunities.

Limits of the Abraham Accords

The second reason the Saudi-Iran rapprochement is important for Palestinians is its relationship to the parallel Arab normalization process with Israel. Given that the Palestinians were the collateral damage of this process — or more likely, at least from Israel’s perspective, a target of it — the derailment of further normalization is a positive result for them.

The Saudi decision (and that of the UAE, which restored relations with Iran in 2022) is particularly important because it defies the rationale and narrative of the Abraham Accords, which oriented around rallying a regional bloc to confront Iran. This, along with the overarching imperative to safeguard America’s security architecture in the Gulf, had provided the motivational basis for entering into those accords.

Indeed, one of the fundamental weaknesses of the Abraham Accords is that it lacked a core achievement. Despite being framed as peace deals, they ultimately amounted to the formalization of diplomatic relations between non-warring states. Furthermore, an agreement that is based on coalition-building for the purpose of enhancing security must ultimately compete with alternatives aimed at achieving the same purpose.

Hence, reaching an agreement with Iran as the principal adversary is more likely to achieve a better result than escalating tensions through a confrontational posture, which would have put the Gulf states in the crosshairs of Iran and its proxies with few ironclad guarantees of help from the United States or Israel.

If anything, the rapprochement with Iran is a demonstration that the Arab states, including the UAE, have been exposed to the limitations of normalization with Israel and the growing unreliability of the United States as a security partner. This realization became acute after both Gulf states suffered a series of Iran-sponsored attacks on their infrastructure and commercial interests between 2019 and 2022, with barely any response from Washington.

This was no doubt a wakeup call for the Gulf states, which began seeking a less-confrontational approach to Iran and other regional adversaries. With Iraq and Oman’s help, reconciliation talks between Saudi Arabia and Iran began in 2020. In January 2021, the Saudi-UAE alliance lifted its blockade of Qatar. A few months later, the Gulf states began diplomatic overtures to Turkey. By the summer of 2022, the UAE and Iran had exchanged ambassadors, with Saudi Arabia following suit in the spring of 2023.

At the same time, the Abraham Accords stalled. No new agreements were forged after Trump left office in January 2021. Sudan has vacillated on its early declaration to join the process; and countries like Oman, which appeared like possible candidates, have enhanced their laws prohibiting any dealings with Israelis.

Most read on +972

Even the UAE, which spearheaded normalization with Israel from the Arab side, has appeared more conflicted of late. The Emirates has used its chair on the UN Security Council for the 2022-23 term to support Palestinian positions and criticize the current Israeli government’s policies. While it is unlikely for the UAE to reverse its formal ties with Israel, its enthusiasm for this process may be waning.

One-track strategy

Ostensibly, all of this is a positive development for Palestinians. Normalization was being used by Israel to undermine Palestinian leverage, marginalize their cause regionally, and pressure them to capitulate to Israeli demands. The Saudi-Iran agreement contrasts sharply with the Abraham Accords, both in substance and effect.

Yet taking advantage of this change is another story entirely. Political fragmentation has denied the Palestinian liberation movement a singular address since 2007 and made regional engagement more complicated.

The PLO/PA under Abbas’s leadership has also proved a poor steward of Palestinian diplomacy: despite three decades of failure, Abbas has doubled-down on the strategy of relying on the United States to deliver a peace deal with Israel, while remaining wedded to the defunct Oslo Accords. Indeed, it was this agreement signed in the 1990s that allowed the Gulf states to more openly engage Israel, and has provided the ongoing context of cooperation that made the Abraham Accords possible.

This one-track strategy on the part of the PLO/PA has taken regional support for granted rather than actively cultivating it. As a result, the PLO’s regional relationships have eroded, its once-strong diplomatic infrastructure has collapsed, and the Palestinian diaspora in the Middle East has fallen by the wayside, denying the liberation movement key sources of support, vitality, and leverage, including vis-a-vis the Arab regimes. The PLO’s aging, corrupt, and bureaucratic leadership are no longer a source of inspiration for the people of the region as they were in the movement’s revolutionary heyday. Although the Arab street remains overwhelmingly sympathetic and supportive of Palestinians, it is not because of their leaders’ efforts, but in spite of them.

Hamas, on the other hand, more closely resembles the PLO of old and has proven itself somewhat better at navigating the regional landscape. While holding firm control in Gaza, its core diplomatic and political leadership are located outside of the occupied territories, where they are not subject to Israeli domination. And unlike the post-Oslo PLO/PA, Hamas does not have a built-in source of financing from a bloc of international donors — a structure which makes the PA not only complacent and unaccountable, but subject to Western and Israeli conditionality.

Hamas still has to be more adept at responding to the vicissitudes of regional politics. But its strategic position is not precluded, like the PLO because of its Western-dependence, from maintaining relations with a diverse cross-section of allies, such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. Still, as long as Palestinian politics remain divided and dysfunctional — hindered even more by the complete absence of democratic national elections, and a restructuring of systems of governance and decision-making — the advantages that have opened in a changing regional context will likely pass the Palestinians by.