Ten years have passed since Israel started building the wall, probably the largest and most expensive construction project in its history, which does not seem to be going anywhere. For four months now I’ve been presenting its story, and now it is time to offer some breaking updates, look into the future, and conclude. The final chapter of the series.

Project photography: Oren Ziv / Activestills

This was supposed to be a four part mini-project for the week of Passover. However, as work progressed, interview followed interview, and the tours along the wall’s route unraveled new stories, and as the gap between the magnitude of the project and the lack of in-depth writing about it in mainstream media became clear – the series grew longer, only to reach its end now.

But before we conclude, some recent important developments must be shared. In the first and eleventh chapters, I mentioned the massive gaps in the wall: dozens of unbuilt miles of the route in the eastern part of Gush Etzion and the Adumim plains near Jerusalem. About four years ago, the state stopped construction in these parts due to the pause in hostilities, insufficient funds, and a fear that U.S. pressure and High Court intervention would make it harder to complete the approved route which effectively annexes huge swaths of Palestinian West Bank lands.

This pause in construction is now coming to an end. A recent statement made in court by the head of the wall project, Colonel Ofer Hindi, indicates that Israel is getting ready to resume construction in these two parts. The statement was confirmed this week by the Ministry of Defense in reply to an inquiry by +972. The confirmation stated that the ministry is currently “conducting evaluations and examining beginning construction of the Gush Etzion route, pending judicial approval. The route in the Adumim plains will be reevaluated over the course of 2013.”

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pxZrUIctF5A[/youtube]

This is big news. Alongside the resumption of deliberation of two petitions pending in the High Court, this could also prompt a revival of the popular Palestinian struggle in the villages south of Bethlehem, possible resistance by settlers in the Gush area, and perhaps even a renewed international interest in the route deemed illegal by the International Court of Justice. In fact, Hindi’s statement has already led foreign diplomats stationed in Tel Aviv who read this series to invite me to share thoughts on the renewed construction for a report to their government.

And two more short updates: in a discussion on the wall’s effects on natural surroundings, I mentioned attempts made by the village of Battir to gain World Heritage Site status from UNESCO in order to stop the wall. Apparently due to internal conflicts within the Palestinian delegation, the UNESCO annual convention has since decided to recognize another local site, the Church of the Nativity and its surroundings, leaving Battir’s ancient terraces in harm’s way.

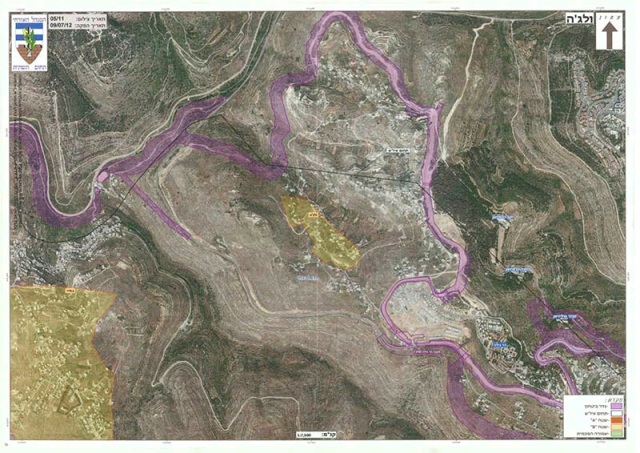

Discussing the misfortunes brought upon the village of Walajah, I wrote that the wall is planned to surround it in all directions. In recent weeks, however, villagers received a new map of the route, which indicates a possible opening in the wall to the southwest. Activists mention that there are not yet any guarantees for this, and that even if this part is left open, the village would still lose most of its lands and be detached from the urban center of Bethlehem and the rest of the West Bank. “Our most minimal demand is to maintain free passage to Beit Jala,” tells me Sheerin al Araj, a prominent activist in the village. “This we have not yet accomplished.”

The wall and the occupation

Throughout this series I tried to focus on the wall itself and its implications, without broadening the argument to the entire system of occupation and settlement. But as I move toward the end, it is crucial to remember how the wall is but one piece in the puzzle of the military regime ruling over the lives of millions, with its two separate legal systems, its home demolitions, its siege on Gaza, and much more. As Haaretz’s Amira Hass always reminds readers, the story of the wall cannot be detached from the permit system put in place in 1991, which has since continuously expanded in extreme ways.

“Many people, including judges we face in court, don’t understand the meaning of occupation’s bureaucracy,” says attorney Shira Hertzanu from Yadin Elam’s law firm, which deals with countless cases revolving around the seam zone on behalf of Hamoked. “Take farmers who want to reach their lands beyond the fence: they might not get an answer for their request for months, then not get it in writing, and procedures keep changing and growing harder all the time. Even when someone is summoned for a hearing at the DCO [District Coordination Office], they might find themselves waiting for hours only to be informed that the officer in charge just isn’t around.

“So people despair. Farmers give up on their trees. People living in the seam zone loose touch with life in the West Bank and consider leaving home and crossing to the ‘Palestinian’ side of the wall. The wall is still new, in many parts less than ten years old, but it’s frightening to see the process of annexation happening in front of your eyes.”

This rationale of the permit system does not only apply to the seam zone, and ones much like it can also be found in the Jordan Valley, and the “special security zones” around South Hebron Hills settlements, and with time in more and more locations across the West Bank. “The notion that a Palestinian would need a permit to get to his land started with agricultural areas that got stuck behind settlement fences, widened dramatically with the wall, and the most recent development is how this is reasoning is duplicated to areas where there is no fence at all,” says attorney Michael Sfard, who is representing villagers from Beit Furik in a petition against the state’s decision to seal off parts of their land in order to protect the settlement of Itamar and its illegal satellite settlements.

“Now the state tells the court that permits can be arranged to enter the zone whenever farmers wish, but knowing the seam way of thinking I’m positive that after the petition is over and done with we’ll hear the army say ‘there’s no reason to farm the land during winter’ or something, and people will lose touch with their land. This is how Israel divides and rules Palestinians and creates apartheid through legal and physical means.”

As recently mentioned here in a different context, and as Noam Sheizaf excellently put it, all these tools of oppression will go on serving Israel for as long as the status quo remains its most rational choice. As long as Palestinian popular resistance and international pressure don’t grow significantly, Israel will not be the one to voluntarily end the stagnation in negotiations, and peace initiatives such as the Arab League’s will remain unanswered. Until such a time of change, the occupation and apartheid are here to stay. And so is The Wall.

The fate of walls and empires

The story sounds so odd that it might actually be true: Scattered reports by activists in Jayous, a single line in a Wikipedia page, and several long posts in a site that went offline sometime after work on this series started all claim that the Scottish town of Falkirk has signed a twinning contract with the Palestinian village of Jayous. A short Youtube clip confirms that even if this initiative is not given official status, there are surely some town people pushing for it.

The reasoning for this move was offered in the now-unavailable site and can still be seen in the clip. Falkirk sits on the old route of the Antonine Wall, built by the Romans to safeguard their northern border in the British Isle. The wall and all its fortifications lasted just twenty years before the empire retreated to its previous more southern border.

The people of Falkirk and Jayous thought that there would be a legitimate symbolism in linking their histories, and thus somehow encouraging the Palestinian village’s popular struggle against the wall built on their lands. The link was also meant as a reminder of the temporary nature of all walls and empires. It is with this reminder to all of us as well that I wish to end.

——

The Wall Project could not have been made possible were it not for the assistance of countless dedicated Palestinian and Israeli activists, extremely patient interviewees, the support of the +972 editors, and of course – my good friend and excellent photographer Oren Ziv of the Activestills collective. All of these I wish to thank deeply.

——

Previous chapters in this series:

Part 1: The great Israeli project

Part 2: Wall and Peace

Part 3: An acre here and an acre there

Part 4: Trapped on the wrong side

Part 5: A new way of resistance

Part 6: What has the struggle achieved?

Part 7: A village turned prison

Part 8: A working class under siege

Part 9: Dividing land – water, fauna, flora

Part 10: My encounters with the wall in space

Part 11: Security for Israel?

And the supplement podcast: +972 bloggers explore Israeli walls and borders