A personal journey

A childhood memory: A group of kids and their teacher on a school trip. They are walking through excavations, listening to explanations from a tour guide about their ancestors who lived there two thousand years ago. After a while, one of the kids points to some ruins between the trees. “Are these ancient homes as well?” he asks.

“These are not important,” comes the answer.

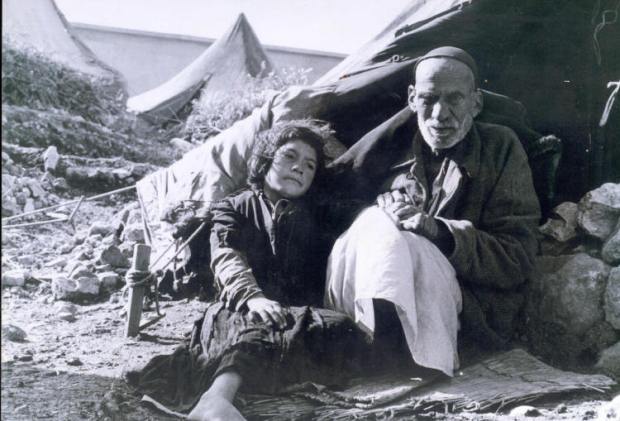

Growing up in the seventies and the eighties you couldn’t miss those small houses scattered near fields, between towns and Kibbuzim and in national parks. Most of them were made of stone, with arches and long, tall windows. In other places they had cement walls. Sometimes all you could see was part of a stone fence, a couple of walls with no roof, or the rows of Indian fig that Palestinians used to mark the border of an agricultural field (it is one of history’s ironies that the Hebrew name of their fruit – the Sabra – became the nickname for an Israeli-born Jew).

Those pieces of the local landscape are gradually disappearing – partly due to the “development” trends which have left very few corners of this country untouched, but also due to a policy that is meant to erase any memory of the people who used to live in this land. But one can still find them sometimes, and in the most unexpected of places –the mosque, which stands between the hotels and expensive apartment towers on Tel Aviv’s beach, or a few homes behind Herzlia’s monstrous Cinema City complex.

As a kid, I never gave those ruins much thought. I loved history – but the history they taught us at school. I could probably have lead a tour of Massada at the age of 12, and one of my favorite books told the tragic story of the last convoy to Gush Ezion in ‘48, before it fell into Jordanian hands.

Once, also during elementary school, our class was supposed to go on a tour of Canada Park, halfway between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. We had been there before – they told us of the crusaders who passed through the area and the caves and homes Jews lived in, and I still remember the explanation on the ways they used to make wine—but this time my mother didn’t want me to go. The park, she told me, stood on the site of the last two Palestinian villages that were destroyed by Israel. Not many remember this story – it happened right after the war in 1967. Imwas and Yallu were demolished under a direct order by Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin. The Hebrew Wikipedia entry states that unlike in ’48, the Palestinian residents were later compensated, but they weren’t allowed to return to their village.

I don’t remember if I ended up going on this trip or not.

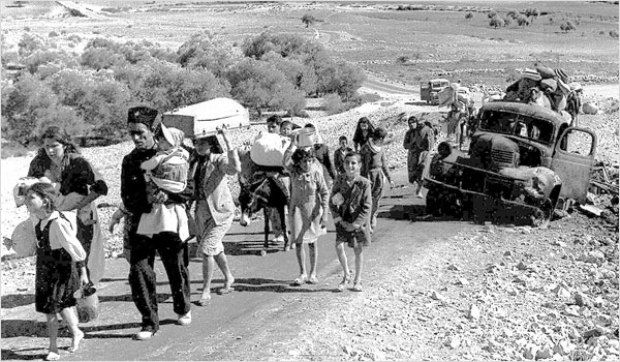

I never heard the word Nakba before the nineties. It was simply not present in the Israeli language, or in the popular culture. Naturally, we knew that some Arabs left Israel in 1948, but it was all very vague. While we were asked to cite numbers and dates of the Jewish waves of immigration to Israel, details on the Palestinian parts of the story were sketchy: How many Palestinians left Israel? What were the circumstances under which they left? Why didn’t they return after the war? All these questions were irrelevant, having almost nothing to do with our history—that’s what we were made to think.

Occasionally, we were told that the Arabs had left under their own will, and it seemed that they chose not to come back, at least in the beginning. Years later, I was shocked to read that most of the notorious “infiltrates” from the early fifties were actually people trying to come back to their homes, even crossing the border to collect the crops from their fields at tremendous risk to their life – as IDF units didn’t hesitate to open fire.

We were made to think they were terrorists…

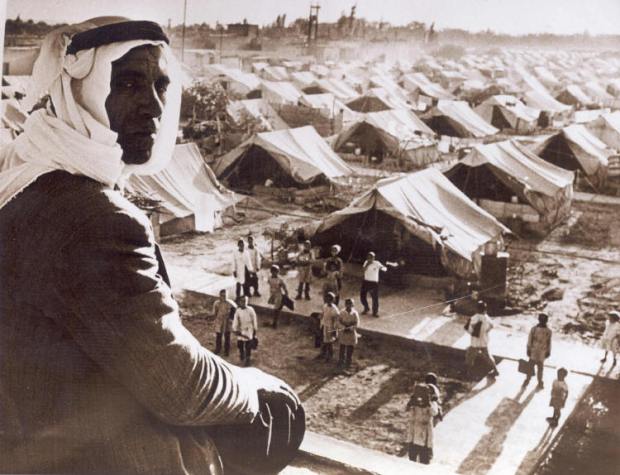

It’s hard to explain the mechanism which makes some parts of history “important” or some elements of the landscape “interesting.” I can only say that looking back, I understand how selective the knowledge we received was. But there is more to this. I think we all chose not to think about those issues. Even after the New Historians of the nineties made the term Nakba a part of modern Hebrew and proved that in many cases, Israel expelled Palestinians from territories it conquered in ’48, we were engaged in the wrong kind of questions, such as the debate on whether more Palestinian were expelled or fled. The important thing is that they weren’t allowed to come back, and that they had their property and land seized by Israel immediately after the war (as some Jews had by Jordan and Syria, but not in substantial numbers). Leaving a place doesn’t make someone a refugee. It’s forbidding him or her from coming back that does it.

For a short while in 2004-2005 I was writing book reviews for Maariv’s internet site, and for several other magazines. I don’t think that I was very good at that, and I still regret a couple of very critical reviews I wrote (I’ve since decided not to review fiction anymore). But I got to read some interesting books I wouldn’t have picked up otherwise.

One of these books was “Strangers in the House: Coming of Age in Occupied Palestine” by Raja Shehadeh, which was translated to Hebrew by the big publishing house Yedioth Sfarim (despite the best efforts by both sides, the hatred and the war, Israeli and Palestinian cultures are still linked to each other in so many ways). Shehadeh was born in Ramallah, the son of an affluent family from Jaffa who left town “for a couple of weeks” during the war and could never come back.

For years, his father would stand in the evenings on the hills of Ramallah and look west, at the aura of his beloved Jaffa.

In 1967, right after the war, an Israeli friend came to visit the Shehadeh family, and the father immediately asked him to visit Jaffa (Palestinians were allowed to travel freely in Israel until 1993). Only when they got there, did Raja’s father understand that his Jaffa was dead. All those years, he was looking at the lights coming out of Tel Aviv.

Maybe it’s because I live in Tel Aviv that this story had such an effect on me. I couldn’t get the picture of the family standing on Ramallah’s hills, looking into the darkness, out of my mind. I thought on the book’s title: who are the “strangers” mentioned there? Is it us, who, in our despair, invaded the Palestinian home, or is it the Palestinians, who found themselves displaced and lost, refugees in their own land?

(The false claim that Palestinians are strangers to this land and only got here because of the Jewish immigration is still pretty common with Israelis. Shehadeh meant it in an entirely different way).

Another Palestinian book I was asked to review was Muhammad al-As’ad’s “Children of Dew” (to the best of my knowledge, this one was never translated to English). The book is not really a memoir, but more of an attempt to reconstruct a picture of the author’s childhood in the village near Haifa out of his fragmented recollections, the stories of his mother and the legends of the village’s people. At the heart of the story is a long convoy of refugees, walking at night east, away from the advancing Jewish army – one of the most poetic and saddest description I’ve read, not because of the horror, but for the desperate attempt to understand what happened, how, and why.

I remembered Muhammad al-As’ad and Raja Shehadeh when last year I interviewed the Speaker of the Knesset Reuven Rivlin, for a piece I did on prominent right-wing figures that were toying with the idea of a one state solution to the conflict. Rivlin, a Likud hawk, grew up in Jerusalem, which was a fairly mixed town before 1948, and certainly more than today. He understood Arabic and had Palestinian acquaintances.

At one point, the conversation reached the idea—popular with mainstream Israeli pundits—that it will be impossible to reach an agreement with the current Arab leadership, which still had many refugees (including Mahmoud Abbas, who was born in Safed). According to this line of thinking, we should look for interim agreements because the next generation, who weren’t displaced themselves, might be more pragmatic.

“Nonsense!” Speaker Rivlin said. “Typical lefty patronizing… the left has always looked down on the Palestinians… [the Jews] remembered our land for 2,000 years, and now you want to tell me that the Palestinians will forget it in ten, twenty years?

“Believe me, they will remember.”

Rivlin does not advocate the right of return for Palestinians and one could also have doubts on the particular joint state he envisions for Jews and Arabs, but at the bottom of his thinking there is a very deep truth: The Jewish people are a living proof that a “refugee problem” won’t disappear for generations, even hundreds and thousands of years, and therefore can’t be ignored.

The Israeli reaction to the mentioning of the Nakba is composed of several elements, each one of them contradicting the other. Some say that there was no Nakba. Then there is the line that suggests that people left on their own will. And if they didn’t – they deserve it, because the Arabs opposed the 1947 partition plan and declared war on the Jews. Finally, there are those who admit that Israel initiated mass deportation and prevented the refugees from coming back—they are even ready to recognize their tragedy, but they simply say that ethnic cleansings are part of the birth of almost every nation. That this is the way of the world – and the Palestinians should simply accept it. Ironically, the latter is the position of Benny Morris, the most well- known of the Israeli New Historian and the person who almost single-handedly proved the claims of forced deportations by the IDF in 1948.

This kind of political argument has recently started to lead to policy decisions, the most prominent of them being the Nakba Law. The original intention of the bill was to completely criminalize any mentioning of the Nakba (with a punishment of up to three years in prison), but this was too anti-democratic even for the current Knesset. The law that did pass forbids government-supported institutions from publicly commemorating the Nakba. The bill is very vague, and theoretically, it could be used to withdraw funds from a university who plans a debate on the Palestinian disaster. More likely though is that it will be implemented against Arab municipalities and institutions who attempt to hold memorial days or ceremonies for the Nakba. It is important to remember not only that some 20 percent of Israelis are Palestinians, but that many of them are refugees – the often-forgotten “internal refugees” who lost their homes and property but found themselves inside Israel at the end of the war.

Speakers for Israel abroad also take part in the Nakba-denial campaign, the latest example being the attempt by trustees of New York City University to refuse an honorary degree from playwright Tony Kushner because he associated the term ethnic cleansing with the birth of Israel. And a few months ago, the Palestine Papers revealed that the US State Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice asked the Palestinian delegation to the peace negotiations to forgo some of their claims regarding the refugees because “bad things happen to people all the time.”

Apart from being so insensitive on a basic human level, such actions—from the Knesset’s Nakba Law to the decision by CUNY’s trustees—ignore one important thing: that the Nakba is part of Israeli and Jewish history.

We have declared a war on our own past.

In 2008 I traveled to the US to cover the Democratic and Republican national conventions ahead of the American presidential elections. I love driving, so I decided not to fly from St. Paul to Denver but to rent a car instead. I decided to pass through every national site I could find on the way, from Mt. Rushmore to Clear Lake, Iowa, the place where music died.

Among the places I planned on seeing was Wounded Knee, in the Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. The Wounded Knee Massacre marked the end of the Native American resistance to the colonization of their land. I remembered reading about it somewhere, and when I saw on the map that the site has been designated a National Historic Landmark, I figured it must be worth a visit.

The problem was that I couldn’t find the place. I passed through the same spot a couple of times, but saw none of the things you would normally see in a national historical site in America. No flags, no museum, no book shop—not even a restaurant. Yet I was positive that I was in the right spot.

On my third attempt I spotted an old metal sign at the side of the road, and on a nearby hill, a tiny graveyard. A sign pointed to the sweet corn stand nearby, but there was nobody there and the window was closed. It was high tourist season.

The entire site was so deserted and sad you could almost feel the ghosts of the dead Lakota people there. Again, it was impossible not to think of the deserted ruins of the Palestinian villages scattered around my country. The American history is probably bloodier than the Israeli, and yes, bad things happen to people everywhere – but is this a reason to forget them? Doesn’t the Palestinian village of Sumail, less than a mile from Rabin square, right at the heart of Tel Aviv, deserve even a memorial site? The last few homes of Sumail are still there, right on one of the busiest junctions of Tel Aviv, but they are about to be destroyed soon, making way for new towers, and a new generation of Israeli kids will be taught in school that the Hebrew city of Tel Aviv was built on empty sand dunes.

Speaker Rivlin is right: The Palestinians won’t forget the Nakba. In many ways, it seems that with each year, the memory is just getting stronger. Meanwhile, all the attempts to forbid any mentioning of the Nakba are hurting Israel’s ability to understand our own history, and not just the parts of it that have to do with the Palestinians.

I was discussing these issues recently with a friend who has a passion for military history. Whenever he can, this friend goes to visit old battle sites looking for old bullets, coins and other modern relics. As part of his hobby, he’s gained a very thorough knowledge of the Nakba, and with time it has beome an obsession on its own for him. Still, he is what Israelis would call a moderate on the political spectrum. The only reason he is looking for these ruins, he tells me, is in order to know our own past. Naturally, he is furious with the Nakba Bill or the recent Anti-Nakba booklet a rightwing Israeli NGO has published.

Yesterday, I got an excited e-mail from this friend. This week he watched Charlie and Half, the Israeli cult comedy from the seventies which is always aired by one of the TV channels on Independence Day.

“It’s actually one of the best documentations of the Palestinians village Sheikh Munis,” he tells me. Charlie and Half, which tells the story of a Sephardic “wise guy,” was shot in Sheikh Munis, which became after 48′ one of Tel Aviv’s poorest neighborhoods, populated with Jews from Arab countries. Most of it is gone by now, destroyed to make way for luxury apartments and the new buildings of Tel Aviv University, but back in 1973, the year the film was produced, the original Palestinian houses and streets were very much present.

Watch, for example, the third minute of the film:

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTqMweVU1v4[/youtube]

The way in which Jews from Arab countries were sent to live in Palestinian homes, only to be evacuated and literally thrown to the streets decades later as the value of the lands soared, is one of the Nakba’s interesting side stories. It’s also further evidence to the fact that forgetting the Nakba actually means not understanding our own history, not understanding ourselves.

It’s not just our sense of guilt for the Nakba that keeps haunting Israelis. In his introduction to Muhammad al-As’ad’s “Children of Dew”, the Israeli editor of the book, Yossef Algazi, who came to know al-As’ad in person, calls the author “A Wandering Jew of our time.” Meeting descendants of Palestinian refugees in the last few years, I couldn’t help thinking about the similarities between Jewish and Palestinian fates, and the sense of displacement the two people share. I think that our real problem with the Palestinians has to do with the feeling that we need to ignore their story in order to hold on to our identity as Israelis – when in fact, we would never feel “at home” without facing the wounds of the past.

“At the end of every sentence you say in Hebrew sits an Arab with a Nargilah (hookah) / even if it starts in Siberia or in Hollywood with Hava Nagila,” wrote the Israeli poet Meir Ariel in his song “Shir Keev” (“Song of Pain”). I think it’s the best political line written in Hebrew. It tells us that whatever we do, regardless of the political solution we chose to advocate or how powerful we might feel, our fate here will always be linked to the Palestinians’.

Denying the Nakba—forgetting our role in it and ignoring its political implications—is denying our own identity.

———————————

Read more in +972 Magazine’s Remembering the Nakba project:

Eitan Bronstein: Nakba Law: Inside Pandora’s Box

Joseph Dana: Occupation & Nakba: Interview with Ariella Azoulay & Adi Ophir

Yossi Gurvitz: Rightwing group publishes Nakba denial booklet

Dahlia Scheindlin: Nakba Law: Is it time for civil disobedience?