This article originally appeared in “The Landline,” +972’s weekly newsletter. Subscribe here.

It is impossible to imagine Israeli anti-occupation writing without thinking of Yossi Gurvitz. A relentless, fearless, incredibly knowledgeable, prolific, and sharp writer, Yossi passed away last week at the age of 53. His death was and remains a shock to many of those who knew him and followed his work. His ability to speak truth to power, while continuing to challenge his own camp, is today more needed than ever.

Yossi revolutionized activist-journalism in Israel, paving a path that many of us would soon walk, and continued after almost everybody else had moved on. An early member of the +972 collective, his contribution to the project was essential — not only because of his articles, which were as popular as they were controversial, but for demonstrating to us all what could be achieved beyond the confines of mainstream Israeli newsrooms.

Yossi’s roots were as far from the left as one could imagine. He was born to a national-religious family and educated at Nehalim Yeshiva, an Orthodox boarding school headed by Yosef Ba-Gad, who would go on to become one of the most right-wing Knesset members of the 1990s. Yossi hated religious studies, and even more so the racism and nationalism he encountered at school, including among the rabbis. Gradually, he began to lose his faith. “I started devouring philosophy books,” he would later write:

With each and every one of them — Nietzsche, alas, was a major influence, but I also read loads of Greek history, and if there is any good antidote to Judaism, this is it — I felt my religious beliefs vanish away. By the time I started grade 11, I was Orthodox in name only. Earlier, I rejected Jewish law as racist; now I could no longer believe in a deity which was managing the world and interested in our lives … The last two years were awful. I could never keep my mouth shut, and as a result got into fights — physical ones — with other students. My rabbi didn’t know what to do with me.

He decided not to continue his religious studies, but rather enlist in the Israeli army. “The military — normally a very oppressive organ — allowed me to complete my coming out,” he wrote of his political radicalization.

Was it the “coming out” in front of his entire community, the intellectual and physical confrontations he endured, that made him such a fearless writer? In real life, Yossi was shy and gentle, but the words he put down on the page were explosive and controversial, even within his own camp. One position that got him in trouble again and again was his insistence that settlers were responsible for some of the violence they occasionally encountered at the hands of Palestinians. He insisted on viewing Palestinian violence in its proper context (a taboo even for many who oppose the occupation), and rejected Israelis’ abuse of the word “terror,” which gradually came to encompass any form of Palestinian resistance, or even existence.

In a 2010 review of a book of soldiers’ testimonies put out by anti-occupation group Breaking the Silence, he wrote:

I have recently finished reading Pity the Nation, by Robert Fisk, which deals with the wars in Lebanon in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly the great Israeli invasion of June 1982 and what followed it. The book deserves its own post, time permitting, but I want to pay attention to one specific point Fisk hammers time and again: the poisonous use of the term “terrorist.” Its usage automatically strips away the humanity of the other side’s militants, and facilitates turning not just them but the people around them and their family members to people whose life are for the taking. Thomas Friedman wrote something similar in his “From Beirut to Jerusalem”: The Israeli soldiers overlooking the Sabra and Shatila camps during the massacre did not hear people being murdered, he wrote, because as far as they were concerned there were no people there, just terrorists.

Though committed to understanding and explaining oppression, Yossi was an old-school liberal who had little tolerance for racism, although he occasionally faced criticism from Mizrahi activists who accused him of making racist and colorblind remarks about Jewish working class communities, who often vote for the right. At the same time, his feminist politics continually earned him hateful comments from the Israeli right on social media, including after his death.

A fresh voice after the Intifada

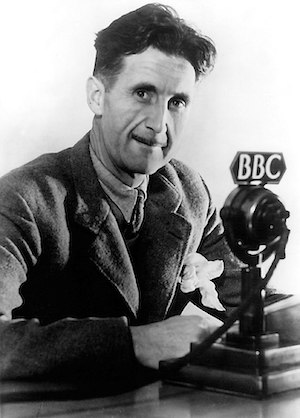

Yossi was an avid student of history, which informed much of his thinking and writing on politics, and worked as a writer and editor on Israeli news sites. In 2006, he launched the Hebrew group blog “Friends of George.” The site’s subhead was originally: “Left-wing and liberal criticism of hypocrisy — in the media, on the left, through intentional blindness — in the tradition of George Orwell.” Soon enough, other members of the project left the site, but Yossi continued on his own, writing thousands of posts. After a while, he changed the subhead of the blog to “Left-wing and liberal critique, and an account of the collapse of Israel.”

Orwell remained a model. “His writing talks about the corruption of language, of leadership, on holding on to ideas even when they are known to be false, on the unwillingness to recognize the horrors you commit, and on the betrayal of intellectuals,” he told me when I interviewed him to a journalistic project on the anniversary of the classic novel “1984.”

True to his idol, Gurvitz never censored himself. He called Israeli journalist Ari Shavit “the last colonialist,” after the latter transformed himself into the darling of liberal American Jews; he saw the dovish Meretz party as part of his own intimate process of leaving the religious world, but left because it supported Israeli apartheid. He denounced the left-wing Hadash party for the support some of its Palestinian members expressed for the Assad regime in Syria.

For several years, he ran the blog of the anti-occupation organization Yesh Din, documenting attacks by settlers and soldiers on Palestinians, and the lack of response by Israeli authorities. He translated dozens of those posts to English, even though he was never required to, so that the world would open its eyes to the daily horrors on the ground and understand how cheap Palestinian life had become to Israelis (early on, he called for an international force to protect them). This was almost a decade ago, when little attention was given to these crimes. Yossi was so blunt that a right-wing group managed to have him questioned by police.

He was most effective in demonstrating to others on the left what could be achieved online, beyond the militaristic and nationalistic confines of the mainstream Israeli media, with no means but one’s own conviction and determination. His was the fresh voice the left needed in the days following the Second Intifada, after the capitulation of its leadership and collapse of its institutions — principled and unapologetic.

He wasn’t the hot-take-never-leave-home kind of blogger. I would see Yossi in Bil’in and Nabi Saleh, in Hebron and Sheikh Jarrah, and at meetings with politicians and at protests in Tel Aviv. It wasn’t always easy to edit him. During his time at +972, his writings on the racism found in some Jewish religious texts was a constant source of editorial frustration. No matter how much the other editors and I explained that some phrases that worked in Hebrew would not translate well into English, and could lead to accusations of antisemitism (or that we should simply pick our battles), Yossi would hear none of it. What made matters worse was that none of us had the depth of knowledge to argue with him.

Yet as much as he was strict about his choice of words, he was easygoing on other matters. An avid photographer, he allowed free use of his photos; he translated texts for free; and he always made sure to give credit and link to others, which was a big deal at the beginning of the previous decade, at a time when Yossi was by far the most widely-read left-wing blogger.

I remember my amazement when I learned that he had 10 times the amount of clicks than our entire site before he joined. Yet Yossi never minded that +972’s fundraising could come at his own attempts to raise money for his blog. What he could not compromise on were his words.

No room for niceties

If pushback is a sign of influence, Yossi had it in spades. He was constantly attacked by the right, verbally and physically, even sued. It is only fitting that the last entry on his blog, written earlier this month, is a defense of a settler, Amiram Ben Uliel — the convicted murderer of the Dawabsheh family — because his confession was extracted through torture.

As always, Yossi ignored the zeitgeist and the politics of the moment. Without mincing words, he directed his anger at Esther Hayut, the president of the Israeli Supreme Court, nowadays the darling of the liberal left and the symbol of the resistance to Netanyahu’s plans for judicial overhaul:

[In convicting Ben-Uliel] Esther Hayut took the side of the dark machine of the Internal Security Service — also because she knew that if Ben-Uliel is entitled to a defense, she will need to open thousands and tens of thousands of [Palestinian] cases in which the evidence was extracted under torture. Esther Hayut knows well what she is protecting. For this crime — for turning a blind eye to the torture of a human being, which begs for the court’s mercy — she will, one day, face justice. May she suffer as did the victims from whom she turned away.

Yossi wrote this on Feb. 7. I last saw him the following day, at an event put on by Breaking the Silence. I asked him for a small favor and he happily complied. A few days later, on Sunday, Feb. 12, he died unexpectedly of heart failure. He was buried in a religious ceremony in Petah Tikva, where he lived; the irony wasn’t lost on those present.

Writing this tribute, I remembered how some of Yossi’s first posts on +972 over 11 years ago were about the killing of Jawaher Abu Rahmah, a Palestinian protester who died following teargas inhalation during an unarmed demonstration in the West Bank village of Bili’in, and whose death the army tried to attribute to other causes. The Israeli journalists who stood near the soldiers echoed the army’s version of the events, but activists and bloggers were able to force the military to retract its false claims. When he wrote about such cases, Yossi would use the term “gunmen” rather than “soldiers,” forcing the Israeli reader to see things — albeit for a brief moment — from the perspective of those facing the end of the rifle.

In his first post on the incident, Yossi spoke about “a wall of denial” that Israelis have built in order to shelter themselves from the horrors of their actions. Breaking through this wall was his life’s mission. It left no room for niceties — what was needed was a big hammer:

Most Israelis, afraid of knowing what the gunmen are doing — these are the neighbors’ kids, after all — prefer to build a wall of denial between them and reality. This denial forces them to become the collaborators of the gunmen; forces them to accept their nonsensical arguments; forces them to become as monsters, even if they did not want to. This denial is the most effective weapon of the IDF, particularly of the IDF Spokesman; it makes certain that the killing may go on without fear, at least not of the home population. The IDF fears only the response of international organizations and courts, which may be a further reason, aside from its proven inability to judge itself, to arraign its gunmen there.

This is how it goes, under Israeli rule: unarmed demonstrators are shot to death, and the fevered mob screams they had it coming. Let us just hope that Jawahar Abu Rahmah’s death may be one of the last, and that her sacrifice will help somewhat to bring down Israel’s rule in the Occupied Territories.