Here’s a strange headline: in the 2023 World Happiness Report, Israel is ranked the fourth happiest country on the planet. We are bested only by the Finns, Danes, and Icelanders, and leave the Dutch, Swedes, and Norwegians in the dust. It is an impressive result at any time, and all the more so while hundreds of thousands of Israelis are on the streets showing just how unhappy they are with their current far-right government.

On the surface, it is remarkable that a country whose citizens are constantly exposed to (and administering) violence, suffering from deep economic and racial inequalities, and facing unprecedented instability — a country recently declared by its own president to be “at the edge of the abyss” — made it even into the top half of the list. So how do we explain this?

Could it be, as suggested in the Jerusalem Post, that “people can personally be happy and satisfied, even though at a national level they may feel that there are dark clouds everywhere”? Perhaps if the sun is bright enough and the hummus delicious enough, happiness can be found even at the edge of the abyss? Maybe. Perhaps the attempt to objectively and quantitatively measure national happiness based on a small sample size is a pointless endeavor to begin with, and this apparent anomaly simply proves that? More likely. But the results are nevertheless interesting, and they merit a deeper look.

First of all: much like Israeli democracy, Israeli happiness is limited to its enfranchised citizen population — a little over nine million people, of whom about 75 percent are Jewish and 20 percent Palestinian. Israel’s disenfranchised, non-citizen Palestinian subjects in the occupied territories, who number almost five million, were surveyed separately; they rank in 99th place, happier than the Moroccans but more miserable than the Iraqis. That there is a huge discrepancy between Israeli citizens and occupied Palestinians is no surprise, but still worth emphasizing.

While most Israelis are not impacted by the political and social turmoil that surrounds them as much as their Palestinian counterparts, they don’t go about their personal lives unaffected by them. How could they? Israelis are obligated to serve in an occupying army — a grueling and exploitative experience at best and deeply traumatizing at worst.

Violence also continues to be shockingly commonplace in civilian life, in the form of crime, police brutality, domestic abuse, and cross-border rockets. Wages are low, the cost of living is high (Tel Aviv was recently ranked the most expensive city in the world by The Economist), and gaps between the wealthy few and struggling majority are ever-growing. Institutionalized racism against Mizrahim and other marginalized Jewish groups, not to mention Palestinian citizens, is as pernicious as ever.

The problems are numerous and deep, and Israelis don’t usually shy away from complaining about them. So the idea that Israelis live some of the happiest lives in the world is simply absurd.

But here’s the thing: the main tool used to measure happiness in the report, the Cantril ladder, doesn’t actually measure happiness in any real sense of the word. Respondents are asked to rank their life on a 1-10 scale, with 1 indicating the worst possible life for them and 10 indicating the best. What the happiness index measures, then, is imagination: the ability to imagine a better life is scored against the ability to imagine a worse one.

It is this exercise in imagination that Israelis scored fourth on, and it is no surprise they placed high on this test. For years, the dominant political discourse in Israel has been an exercise in stifling imagination. Indeed, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s entire political career has been predicated on the idea that despite life under his rule being objectively pretty awful, it is in fact the best life we could ever hope for.

Utopia no more

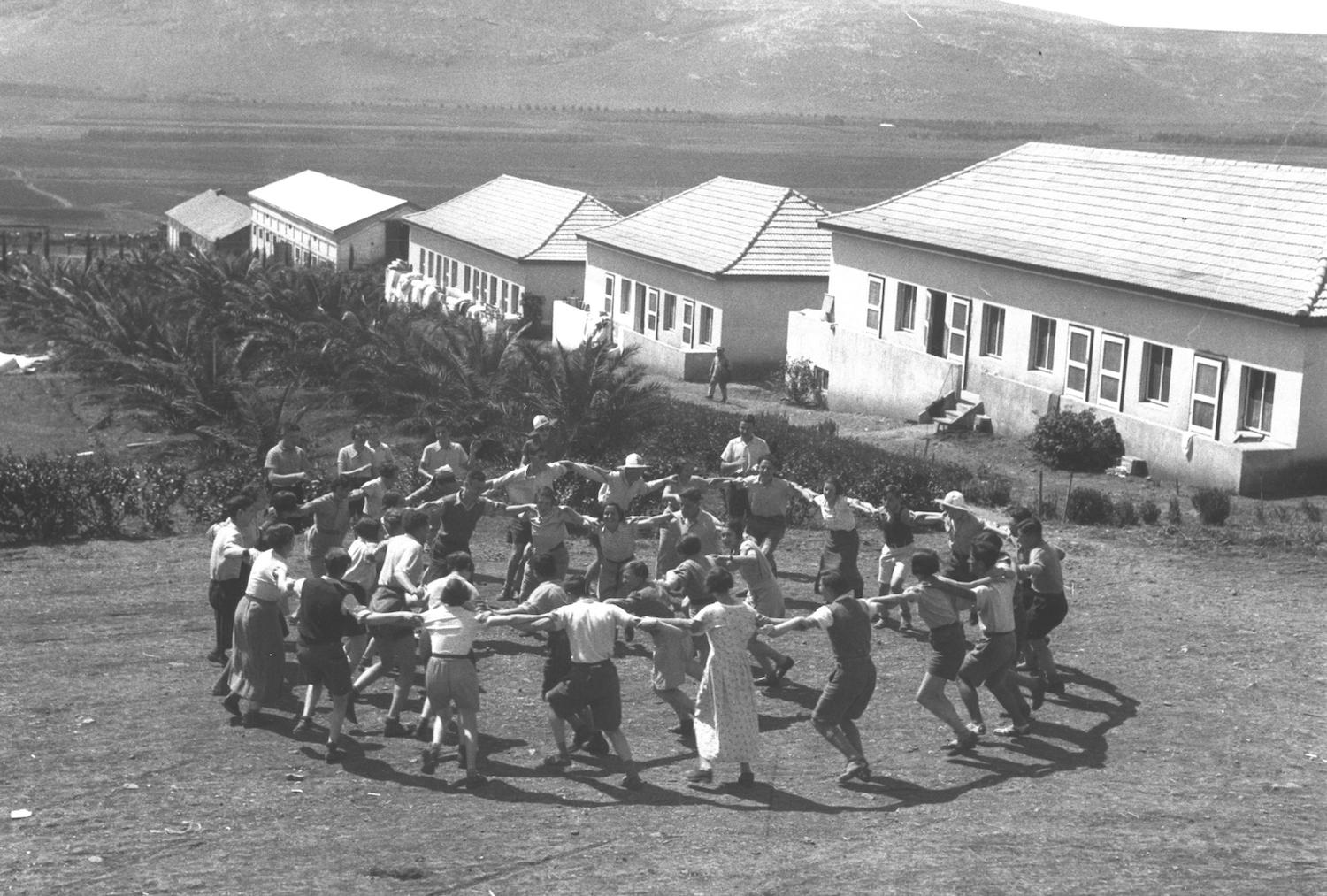

It hasn’t always been like this. Zionism began as a utopian project, and for its first few generations it sparked the imagination of dreamers spanning across the political spectrum, from communists to right-wing Revisionists.

Most of these dreams were eventually abandoned, each for their own reasons. Some of them may have failed because they were built upon contradictions. The fall of the kibbutzim, for example, is famously romanticized as a lost dream, but these supposedly socialist utopias were in reality gated communities that offered socialism almost exclusively to European Jews and, by way of land grants, dispossessed not only the indigenous Palestinian population but also the decidedly non-utopian “development towns” built for Mizrahi citizens.

Today, the only utopic vision still going strong is the messianic Zionism of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, which underwent a fascist evolution at the hands of the followers of the extremist American-Israeli rabbi, Meir Kahane. The dream of a halakhic kingdom, a Third Temple on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, and a “decisive” victory over the Palestinians is seen by many on the far right as closer than it has ever been, making them very happy indeed. That vision’s adherents — in the hilltop youth, the Knesset, and the National Security Ministry — certainly don’t lack imagination.

Though once numerous, utopian idealists were never the majority. To most Israelis, Zionism’s central promise was simply to create a safe haven for the world’s Jews. My communist grandparents, for example, became Zionists after surviving the Holocaust because Zionism promised them that safe haven. Their children remained Zionists even as they shed the dream of communism, essentially because they believed in that promise of safety, if nothing else.

Most read on +972

But safety never came. A state of emergency was declared in 1948 and was never lifted, not even for a single day. Wars follow wars, with periods of relative stability seen as mere intervals between the last escalation and the next. Instead of sending our children to college we send them to the police and torment an occupied population, where they risk bodily injury and death and where moral injury is guaranteed.

When I was growing up, I was still told that this is a temporary situation, that peace will come, it’s only a matter of time — maybe I won’t even have to go to the military when I grow up, who knows. Today, children are no longer taught that. The status quo is all we have.

A telling symbol of this has been the emergence of the idea of “managing the conflict,” or, more recently, “shrinking the conflict.” Almost no one in Israel today believes that the constant violence between Israelis and Palestinians will ever end. There is no solution; at best, we can contain it by keeping Israeli casualties at some acceptable rate, crushing Palestinian uprisings as they inevitably emerge, and periodically “mowing the lawn” in Gaza and southern Lebanon to keep Hamas and Hezbollah in check.

This depressingly predictable routine is all that an entire generation of young Israelis has ever known. With slight variations, this is the policy not only of Netanyahu but also of his main “centrist” rivals, Benny Gantz and Yair Lapid. Zionism’s promise of safety devolved into Netanyahu’s promise that “we will forever live by the sword.”

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when this extreme stifling of the Israeli imagination started — perhaps with then-Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s assertion that “there is no Palestinian partner for peace” in the early 2000s; perhaps with Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination back in 1995. The two-state solution, flawed and conservative as it was, at least allowed Israelis to imagine a future of peace. There is almost no one in Israel who still seriously believes in it. With its death, and with no immediately viable alternative (a one-state solution in which every person between the river and the sea receives equal rights is far too radical for most Israelis to consider), the miserable status quo has been widely accepted as the only possible reality.

Following this development, the “conflict” gradually disappeared from the news. It is hard to explain just how little the average Israeli cares about government policy in the occupied territories, unless it is directly related to “security” or “terrorism.” Even the impressive (and, at its fringes, positively heroic) protest movement against Netanyahu’s judicial overhaul is inherently conservative, seeking to “save Israeli democracy” — something that has clearly never existed for five million of the state’s subjects.

Even when they are lighting fires in the streets, Israelis struggle to imagine a better future. At best, they can imagine only more of the same.