“It’s like a death in the family,” read one Facebook comment. “There is a sense that all the lights are going off in this place,” someone else replied. “The end of an era,” a third mused.

These were just a small sample of the responses to the announcement in late October by Haokets (“The Sting”), an independent online publication, that it “will close its doors and retire” at the end of the year.

Such reactions to the closure of a small media outlet may appear dramatic, but they are testament to a very particular lacuna that Haokets has filled since it launched in 2003. For almost two decades, Haokets has effectively served as the ideological home of Israel’s Mizrahi left. For a community of academics, activists, writers, and poets who had once felt politically adrift, the site has provided a vital platform for understanding the experiences of various oppressed communities between the river and the sea as interconnected struggles. The announcement that such a rare and meaningful space would be closing was thus, naturally, a source of great distress.

To understand why requires interrogating the precariousness of the Mizrahi left camp since its very inception. On the one hand, Mizrahim [Jews who immigrated to Israel from Middle Eastern, North African, and West Asian countries] have faced more than 70 years of discrimination and marginalization in Israel. On the other hand, throughout these decades, the Mizrahi struggle — which seeks an equitable redistribution of the country’s resources and the recognition of past injustices — has been almost completely absent from the agenda of the Israeli left.

The Mizrahi left therefore represents a distinct voice of opposition on several fronts: to the right-wing policies of successive Israeli governments; to the ongoing marginalization of Mizrahim under Israel’s Ashkenazi hegemony; and to an Israeli left that, more comfortable discussing the post-1967 occupation than injustices within the Green Line, continues to sideline and even obstruct the Mizrahi struggle. Now, however, this political movement finds itself at a crossroads.

Haokets’ predicament points to a much deeper crisis for the Mizrahi left and its struggle within Israeli society, which has in recent years been increasingly usurped by the political right. Facing an uncertain future, many inside the movement are seeing the site’s peril as a moment for reflection and for imagining new directions.

Yossi Dahan, who is one of the magazine’s two founders and remains involved with the site, explained to puzzled observers in a subsequent Facebook post that the magazine simply ran out of funding: “We arrive at a situation, after all the fundraising options have been exhausted, where it is not clear how it will be possible to pay salaries to our staff in a few months.”

Haokets has always been a low-budget operation; for much of the past decade it has employed only two or three part-time editors and one administrative staff member. It has never been able to pay its hundreds of contributors, nor has Dahan himself ever taken a salary despite having been involved in running the magazine for the past two decades.

When Dahan established Haokets nearly 19 years ago with his friend and fellow academic Itzik Saporta, they were even paying out of their own pocket. The two had become acquainted as members of the Mizrahi Democratic Rainbow Coalition (“HaKeshet” in Hebrew) — a collective of scholars and activists promoting Mizrahi equality in Israel — and, in an era before social media, decided to set up a blog through which to spread a political-economic analysis that was almost totally absent from the Israeli media landscape.

“Itzik and I were quite frustrated with the established Israeli media and how they cover all kinds of issues, especially socioeconomic and cultural issues,” Dahan explains in a phone call soon after the announcement. Compared to the public discussion around these topics in other countries, they were dismayed at the “poor and restricted” Israeli discourse; in particular, the pair had grown “frustrated with the Israeli left on economic issues.”

Whereas in most political contexts the left/right spectrum indicates the extent to which parties or individuals support the equal distribution of resources, in Israel, the distinction is more about where one stands on the question of Palestine. Class issues have little bearing on Israel’s left/right divide; in fact, the support base of Labor and Meretz, considered Israel’s mainstream left parties, tends to comprise the wealthiest sectors of society, which remain, in large part, Ashkenazi.

This aberration is partly what makes it so hard for Haokets to raise the funds it needs to operate. Dahan tells +972 that the magazine’s financial troubles are largely a reflection of its dual readership: Mizrahim on the one hand, most of whom do not identify as left-wing, and the Israeli left on the other hand, most of whom are Ashkenazi.

As a result, while Haokets’ Mizrahi audience appreciated the focus on socioeconomic disparities and ethnic discrimination, the same audience complained whenever it wrote about the occupation. Left-wing Ashkenazi readers, meanwhile, were excited that Mizrahim were talking about Palestinian rights but disgruntled that they brought up intra-Jewish ethnicity, deeming it an unimportant or unnecessarily divisive topic. “It’s very difficult to raise money when you have audiences that like you but also hate you at the same time,” Dahan jokes.

Nonetheless, the blog quickly garnered a loyal following, especially among those who both shared the authors’ leftist politics and agreed with their critique of Israel’s dominant left-wing frameworks. “It became very important for me to read stuff on Haokets,” says Yonit Na’aman, a poet and literary editor who would later become the site’s editor. “It became my daily routine, reading Itzik and Yossi’s posts.”

Before long, Na’aman contributed her first article to the blog on the topic of anti-Mizrahi racism in academia, following a lecture by Antiguan-American writer Jamaica Kincaid at Tel Aviv University. When Professor Smadar Lavie, a prominent Mizrahi academic, asked Kincaid how she views the marginalization of Mizrahim in Israeli academia, Kincaid responded, to Na’aman’s disappointment: “I was told when you visit someone you don’t judge them.” The audience was pleased with the answer; some scolded Lavie for even asking the question.

In contrast, just a week earlier, the Jewish American academic Judith Butler had given a talk in the same lecture theater expressing a strident critique of the Israeli occupation, and none of the attendees batted an eyelid. “It was so brutal to compare the two incidents,” explains Na’aman. Haokets provided her the platform to meditate on the racist assumptions underlying Israel’s left-leaning academy.

Connecting the ‘social’ and the ‘political’

In 2011, Na’aman became one of Haokets’ two editors alongside Tammy Riklis, after grants from the New Israel Fund and the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation enabled the expansion of the blog into a digital magazine with salaried staff [full disclosure: Rosa Luxemburg Foundation also funds +972 Magazine]. “It was an interesting moment to join,” says Riklis: Israel’s biggest ever social justice protests were just exploding into life, with tens of thousands of citizens taking to the streets all over the country to demand a change in the social and economic order — most famously in the form of a tent encampment on Rothschild Boulevard, the pinnacle of Tel Aviv’s financial district.

Despite its intentions, the protest movement was largely blind or dismissive to the fact that not all Israelis experience poverty equally. “Ethnicity was not a part of the language at all,” Riklis recalls. “You wouldn’t even say back then ‘Ashkenazim and Mizrahim.’” In the face of this erasure, Riklis says, Haokets “gave a platform to critical voices” — among them Mizrahim from south Tel Aviv who established an alternative protest camp in Levinsky Park, a location heavily associated with Israel’s marginalized populations and the poverty they experience.

Throughout this febrile period, Haokets also published a series of articles by Israeli sociologist Shlomo Swirski, the longtime academic director of the Adva Center (of which Yossi Dahan is also the founder and chairperson). In the 1980s, Swirski wrote one of the earliest academic critiques of Israel’s “melting pot” absorption policies which, he argued, laid the foundations for decades of discrimination.

The articles Swirski wrote for Haokets during the social protests were collected into a booklet and handed out at the protest camp, highlighting the uniqueness of what the site sought to achieve: bringing together the voices of activists alongside those of academics, and refusing to make a choice between the “social” — the ethnic and class-based discrimination faced by Mizrahim and other groups in Israel — and the “political” — the questions of occupation, conflict, and colonialism vis-à-vis the Palestinians.

It was around the time of the 2011 protests that Sapir Sluzker-Amran, who has spent much of the subsequent decade active in Mizrahi, feminist, queer, and public housing struggles, began reading Haokets. “The things I read there were like a political school for me,” she explains. “People were writing very interesting and radical things that I couldn’t read anywhere else, definitely not in Hebrew and definitely not in a manner that allowed me to connect to them.

“It came from a complex direction in the political map,” Sluzker-Amran continues. “Yes, a Mizrahi left, but a left that was different from the left that I knew growing up in a right-wing home. It highlighted the complexity within different struggles and within diverse populations.”

Having since contributed several articles to the magazine, Sluzker-Amran notes that Haokets is “one of the only platforms in which we were able to write from within the struggle. It’s an activist community which encourages us to respond to each other in a way that advances our struggle and our thinking.”

The online community debates generated by Haokets were, for left-wing Mizrahi activist Orly Noy, who is also an editor at Local Call and writer for +972, the most valuable part of what the magazine offered. “The articles were kind of a gateway to the brilliant discussions,” Noy explains. “You would read an article in Haokets, and then sometimes there were over a hundred comments, and that was the core of what was happening.

“As a reader,” she recalls, “it was such a privilege to just be a fly on the wall. For a long time I didn’t dare even participate in the discussions, I was in such awe. Sometimes it would get heated but it was always sincere and a very friendly, accepting, open space. It really created a community.”

Especially prominent in the Haokets community’s collective memory is a groundbreaking article written in 2008 by Ortal Ben Dayan, then a graduate student at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem [full disclosure: Ben Dayan is married to Haggai Matar, the executive director of the NGO that operates +972 Magazine]. After entering into and then ending a consensual relationship with one of her professors, he subjected her to sexual harassment and racist abuse. Ben Dayan decided to write about the episode, and chose Dahan and Saporta’s blog as the place to do so.

“It felt very natural to publish it in Haokets,” she explains. “I was really at the start of my journey as a Mizrahi activist, but I was already reading what the experienced activists were writing there. I remember Yossi’s reply when I sent him the text: ‘Are you sure you want to publish it in your name?’ And I said ‘Yes, in my name.’ But I had no idea what the article would do. I couldn’t imagine. My life was turned upside down the moment it was published.”

Ben Dayan’s article resulted in the exposure of several more professors who had harassed their students — initially through readers’ comments on the blog itself — and forced university administrations across the country to confront the reality of the problem. What began as a single essay on Haokets led to a total transformation in the way Israeli universities handle relationships between faculty and students. “The situation before my complaint at the university and the situation after are two different worlds,” Ben Dayan says.

From the streets to the academy

The Mizrahi left agenda that Haokets consolidated over the past 19 years is rooted in the decades-old resistance of Mizrahim to their oppression at the hands of the Ashkenazi-Zionist establishment in Israel. Such resistance dates back to the earliest years of the state, when the Mapai government, an earlier incarnation of today’s Labor Party, settled waves of Jewish immigrants from the Arab and Muslim world — often by deception — in desert camps or crammed them into the properties of Palestinian refugees.

Throughout the 1950s, Mizrahim in ma’abarot [transit camps] and so-called development towns engaged in sporadic acts of rebellion against their second-class treatment and against their barriers to employment and housing, which Ashkenazim who immigrated during the same period did not face.

A much larger, unified uprising erupted in Haifa’s Wadi Salib neighborhood in 1959, and in 1977, a “ballot box revolution” saw Mizrahim categorically reject their Labor rulers — swinging that year’s national election for the right-wing Likud party, which continues to enjoy widespread support among much of the Mizrahi public more than 40 years later.

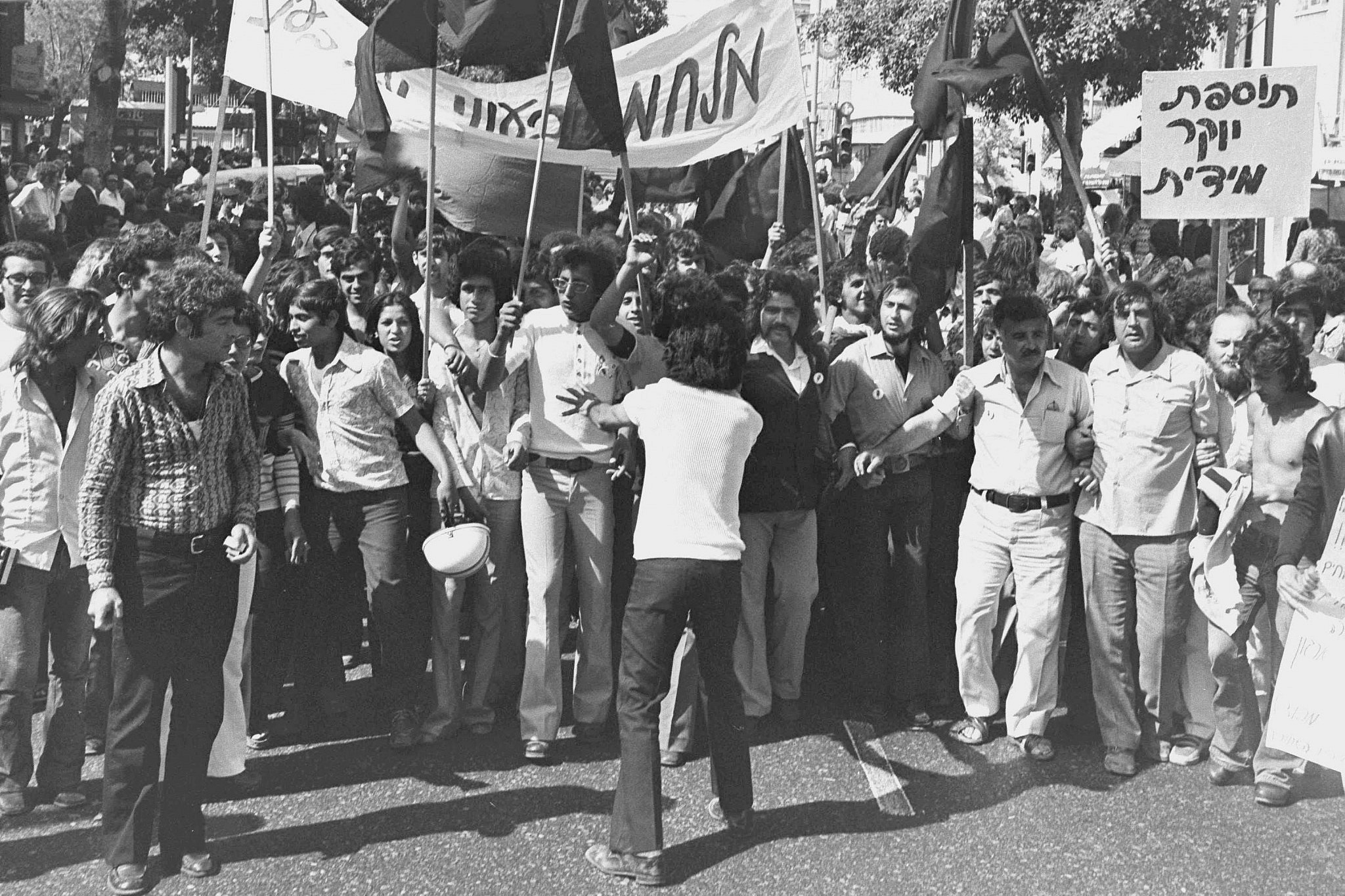

The most famous Mizrahi resisters, though, were the Israeli Black Panthers, who were most active in the early 1970s. The leaders of the Panthers had grown up destitute in Musrara, a formerly Palestinian neighborhood of West Jerusalem into which Jewish immigrants from North Africa had been settled by the state in order to prevent the return of Palestinian refugees, and to populate — and therefore act as a buffer in — the area close to the Jordanian border.

Taking inspiration from the Black American movement whose name they borrowed, the Israeli group mobilized mass demonstrations throughout 1971-72, which were brutally repressed by Israeli police under orders from Golda Meir’s Labor government. The momentum the Panthers had generated for the Mizrahi struggle was interrupted, however, by the outbreak of war between Israel and Arab states in 1973 — with the “political” once again taking precedence over the “social.”

At the time of the Panthers’ protests, a majority of Mizrahi adolescents were not in school, and Mizrahim comprised only one percent of Israeli university students. “If you think about the Mizrahi struggle,” says New York-based Mizrahi academic Zvi Ben-Dor Benite, “until the late 1970s, its true leaders were people who were not educated in the Israeli sense. The leaders of the Black Panthers were young, they were workers, and their politicization came through action and self-education rather than through studying.”

It was in the 1980s that the “Mizrahi scholar-activist” appeared, Ben-Dor Benite says, tracing this development to Yossi Dahan’s generation, which provided inspiration for his own subsequent cohort of scholar-activists and resulted in the founding of Tzedek Hevrati (Hebrew for “social justice,” and known by the acronym Tzah) in the early 1990s.

That decade was a high-point for this kind of Mizrahi activism, which grew out of, and was largely focused on, the Israeli education system. After Tzah came Kedma, a network of alternative schools that built on the critiques voiced by a Mizrahi-led organization called HILA, made up of parents from development towns and working class neighborhoods that fought for education equality in the late 1980s. Then came the establishment of the aformentioned HaKeshet in 1996, before the Mizrahi feminist movement Achoti was born in 2000.

Ben-Dor Benite sees Haokets’ primary contribution to the Mizrahi struggle as being a process of legitimization. “I think today Mizrahi activism and research agendas in the universities are much more accepted, and that’s clearly what feeds into Haokets and is fed by Haokets,” he says.

Betty Benbenisti, who studied the Haokets community for her ethnographic PhD research, agrees. “Twenty years ago,” she says, “when I was the spokesperson for an NGO, I would call up a newspaper in Israel and ask if they had someone reporting on social issues. They would say ‘yes, of course’ and then refer me to the gossip column. The term ‘social’ didn’t exist back then as we refer to it today.”

Haokets’ impact is also seen in the success of the struggles for which it has provided a home. Central among these is the Yemenite children affair, in which state authorities forcibly “disappeared” thousands of Mizrahi babies in the 1950s. “Haokets was the main media outlet supporting the families affected, publishing their evidence, and really challenging the way Israelis think about this affair,” says Tom Mehager, head of the Amram Association, which calls on the state to recognize its responsibility for the acts.

“Unlike with other outlets, you never have to fight the Haokets editors just to write about this topic,” Mehager continues. “So we published a lot of op-eds and family testimonies there for years before it became more mainstream.” Whereas for decades the Israeli media was central in suppressing public consciousness on the affair by ignoring and denying the claims of the disappeared babies’ families, “nowadays mainstream outlets talk about it as something true that happened. But we definitely needed Haokets to do the first step: to collect our community together and publish our truth. They planted a lot of seeds for the Mizrahi struggle, and we see now how they bore fruit.”

The Haokets community has even produced politicians: first Yossi Yona, an associate professor of education at Ben-Gurion University, and Na’ama Lazimi, both of whom entered the Knesset as members of the Labor Party in 2015 and 2021, respectively. “Haokets was like a home for me,” says Lazimi, who serves as an MK in the current government. “I was in shock when I heard that it’s closing. I think Haokets is more essential today than ever, with the rise of libertarian forces in Israeli politics like Kohelet Policy Forum and The Tikvah Fund.”

It is no coincidence that the struggles Lazimi champions in the Knesset are those most closely associated with Haokets. “My political identity was refined through reading articles on Haokets when I was younger,” she explains. “It was a very unique platform, of a real, popular left. It took issues of poverty, exclusion, racism, inequality, occupation, and injustice, and put them together in a way that allows you to see the full picture. If you ask me what the left should look like in Israel, I would say it’s what Haokets looks like.”

‘People don’t talk about Mizrahim and Palestinians in the same sentence’

Around five years ago, Haokets underwent another expansion, this time to incorporate an Arabic website alongside the Hebrew one. Seeing that content relating to Mizrahi Jewish history and identity was not available to an Arabic-speaking audience, the team decided to hire another part-time editor who would translate material from the Hebrew website into Arabic, in addition to curating original Arabic content.

“A staggering number of people from the Arab world were reading these articles,” says Dahan of the added website. “It made us realize that Arabs don’t know the history of Jews who left the Arab world in the 1950s, and they’re very excited to read about this void,” adds Riklis.

For much of the past five years, the role of Arabic editor was filled by Kifah Abdul Halim, a Palestinian writer and translator who is a citizen of Israel [full disclosure: she is also board member of +972 Magazine]. Abdul Halim says that some of the site’s most popular articles received more than 50,000 views from Arab countries, and were especially popular in Egypt and Morocco. “It’s because it’s so unique,” she says. “There is no other platform where you can read about Arab Jews in Arabic and learn about what happened to the Jews who left the Arab world.”

The Arabic website created a kind of two-way dialogue between Haokets and the Arab world. Readers would write in thanking Haokets for the articles, grateful for the opportunity “to learn what happened to our Jews.” And when Abdul Halim encountered difficulties in translating a piece, she would collaborate with translators from neighboring countries. “Once, for example, I needed to translate a very old poet who wrote in Biblical Hebrew. So I contacted an Egyptian translator who works with Biblical Hebrew at his university,” she says.

While the vast majority of the Arabic website’s readers were located outside Israel, it was also read in part by Palestinian citizens of the state. The two distinct audiences were often attracted by specific content: “Stories about the history of Jews in the Arab world, and the relationship between Mizrahim and the Arabic language — all this was more relevant to Arabs abroad,” says Abdul Halim. “But articles about the occupation, and about social and economic issues in Israel like workers’ struggles, women’s rights, and civil rights — this was more relevant to Arabs here.”

Abed Abu Shehadeh, a Palestinian activist and member of the Tel Aviv-Jaffa city council, has been writing for Haokets for the past several years. He describes the themes of his writing for the magazine as being “super urban,” presenting the day-to-day realities of living in Jaffa. “Most Palestinians inside and outside of Israel tend to romanticize Jaffa as a Palestinian community that is holding its ground and fighting gentrification,” he says. “I also write about the ugly parts of Jaffa: about the crime, about the drugs, about the killings, about what it means to lose friends in the city — topics that don’t get enough discussion.”

Abdul Halim sees Haokets as uniquely able to draw connections between the Palestinian and Mizrahi struggles. “For me, an Arab living here, the issue of land and housing is very important,” she says. “It’s the same for Mizrahim: they speak a lot about land, about housing, about how the government distributes the different resources and budgets, so there are lots of connections.

“This is not a common discourse,” Abdul Halim continues. “People don’t talk about Mizrahim and Palestinians in the same sentence. People think recognizing the suffering of others will weaken your argument because you’re not the only victim. But if you see the connection, you can actually make a stronger argument — that I’m not the only one suffering, and that it’s actually a hierarchy of oppression. There are the Ashkenazim, and then the Mizrahim, and then the Ethiopians, and it’s the same mechanism working on everybody.”

Abu Shehadeh concurs. “The tragedy is that we can’t even imagine a shared reality or a shared future for Jews and Palestinians here. In order to do so, we have to imagine the people with whom we will share this space together. The people I worked with at Haokets are the people I want to imagine a shared future with.”

The struggle to save Haokets

Almost immediately after the announcement of the site’s closure in October, the Haokets community sprung into action. Meir Amor, an academic who has written dozens of articles for the magazine, sought to gather a group of people who could provide grassroots financial support. Before long, it became clear that “there were so many people who were ready to contribute some of their income on a continuous basis to keep Haokets alive,” Amor says. Although this alone was not enough to ensure Haokets’ long-term survival, Dahan nonetheless took an interest and agreed to discuss funding options.

After two meetings, the community decided to pursue two routes of action: setting up a membership model based on fixed contributions, and establishing a cooperative that would work longer-term to oversee Haokets and expand its operations. “We’re aiming to create a social community that will also engage in research and culture,” says Meir.

For Na’aman, the efforts to keep Haokets running are “very touching,” but she doesn’t know if it will be enough. Riklis believes that the problem is systemic, due to the identity of the magazine’s readership. “The fact we’re closing,” she told +972 soon after the initial announcement, “shows that money is still not in the pockets of, or available to, Mizrahi Jews. Of course there’s social mobility and Mizrahi Jews are becoming more and more a part of the middle class. But the big money, the big foundations, are still very much not buying into the Mizrahi discourse.”

It is much easier, Riklis explains, for foundations in the United States to understand the language of what she calls the “white left,” which views the post-1967 occupation as the principal injustice in Israel-Palestine that needs remedying. “But for these foundations to understand our point of view… it’s not a common one, and it doesn’t translate easily into the liberal voice, which is usually where the money is coming from.”

Then came an update from Dahan in late November: another foundation, the Emile Zola Chair for Human Rights, had reached out and offered a grant of NIS 40,000 for each of the next two years. Along with the continuing support of the New Israel Fund, this would enable Haokets to continue operating at least for a few months longer than originally planned. “We’ll continue so long as the money allows us to,” Yossi affirms, although he also seems doubtful about the longer-term prospects.

In the wake of this additional source of funds, the team released another statement on Facebook in December announcing that “Haokets is not closing, for the time being!” and inviting readers to support the crowdfunding efforts. “About a hundred people have expressed a desire to contribute to the site regularly, and further creative efforts are being made to acquire the resources that will enable us to continue,” the post said. However, given that the systemic problems haven’t gone away, just how successful this endeavor will prove remains to be seen.

A new generation takes the reins

Regardless of whether Haokets will survive for a few more months, a year, or another two decades, its financial difficulties are emblematic of a deeper moment of crisis for the Mizrahi left in Israel. Amor doesn’t mince words: “The Mizrahi struggle basically failed, and we continue failing.

“We are living in a Jewish state that actually oppresses Jews, but you’re not allowed to say that,” Amor continues. “Mizrahi existence is a tragic existence in Israel, and it’s a tragedy that is dismissed, ignored, and repressed. Haokets is one of the only places in which this tragedy is expressed openly and articulated politically.”

For Ben-Dor Benite, the predicament derives from a shift in emphasis in the Mizrahi struggle following the rise of a Mizrahi middle class. “If up until the late 1990s the Mizrahi struggle was squarely class-based, with a focus on health, education, housing and labor, today it’s more about images of discrimination and Ashkenazi arrogance.”

This shift, he argues, is what has allowed the right to appropriate the Mizrahi discourse in recent years — a process that has been spearheaded by a cluster of high-profile right-wing Mizrahi ministers in recent Likud governments, including members of Knesset such as Miri Regev, Amir Ohana, and Dudi Amsalem. “Arguments that we used to make in the 1980s are now arguments that some right-wing politicians make on the podium — even Benjamin Netanyahu himself sometimes, when he was prime minister,” Ben-Dor Benite says. “The Mizrahi struggle has been hijacked into a politics of resentment, and the Mizrahi left don’t know how or if they’re going to relate to that.”

Haokets is by no means the only organized expression of a Mizrahi left agenda which is struggling to survive. Sigal Haroush-Yonatan, who is active with HaKeshet (Mizrahi Democratic Rainbow Coalition), says the organization is today “in a stage of reorganizing” after 25 years of activity, which most notably included a landmark 2002 Supreme Court ruling against unequal distribution of land. “I cannot say what will happen in a year or two years with HaKeshet,” she says. “We don’t want to close, but right now, if you want me to be honest, it’s a time for questioning.”

One of the main problems, Haroush-Yonatan explains, is that “another generation has risen up and is doing things differently.” Orly Noy agrees: “Haokets had a very significant role in crystallizing a radical, humanistic, leftist Mizrahi voice. But the next generation of Mizrahi activists rebelled against it to a certain degree, and that voice was shattered.” Instead of fighting to change the system, Noy says, some of the newer activists sought to “join the system and have their part of the power,” including groups like Tor Hazahav, that promote a Mizrahi Zionism and a return to traditional (“masorti”) Judaism.

Riklis believes that the Ashkenazi-dominated left-wing parties share plenty of blame for this state of affairs. “Meretz and Labor should go to the periphery and do their job, but it doesn’t happen,” she says, referring to the disinterest of mainstream left parties in areas of the country where most Mizrahim live, except when it comes to courting votes during election season. “Likud does it, and that’s why the election results are like that.”

Haroush-Yonatan takes this further: “More and more people on the Mizrahi left are coming to the conclusion that the Israeli left is not our partner, and there is a feeling that we can achieve more by partnering with the Likud or with Shas. We got a slap in the face in the last year and a half,” she continues, “after the ‘Asi struggle’ and all these other struggles.”

The Asi River made headlines in recent months amid protests by residents of Beit She’an, a working class Mizrahi city in northern Israel, who have been demanding that Kibbutz Nir David open its gates and allow everyone, not only members of the historically Ashkenazi kibbutz, to enjoy the river which runs through it. Meretz and Labor, as well as many of their supporters, have sided with the kibbutz, as opposed to prominent members of Likud and Shas, who backed the residents of Beit She’an. “We always thought we were [politically] left,” she explains, “but can I stay with this left if it hates me?”

Amor, meanwhile, dismisses the notion that Mizrahi interests are better represented by right-wing parties as “nonsense.” He recalls an incident from 2018 in which Netanyahu, then prime minister, spoke at an event in the predominantly Mizrahi city of Kiryat Shmona, where a local resident berated him for having overseen the closure of an emergency room that previously provided treatment for her medical condition. Netanyahu’s response was simply to tell her: “You’re boring.”

“This is exactly the Likud’s attitude toward health, education, housing, labor, transportation, all these issues,” says Amor. “You see it also in the expulsion of families from Givat Amal, which is an ongoing issue over the last 70 years — no one gave a shit about these people, including in Likud.”

“You can always say that everything is the fault of the Ashkenazim,” says Ben Dayan, “but in my opinion that’s a very partial explanation.” In her eyes, there is a more pressing question at stake: “How did it happen that we succeeded in bringing the Mizrahi discourse mainstream, but we didn’t succeed in bringing the Mizrahim to the left? There needs to be new thinking. What’s our place today, now that right-wing politicians are speaking our discourse? These are the questions that needed to be asked in Haokets.”

At the magazine, she believes, “there stopped being a vision of what the Mizrahi left discourse should look like and what it should be advancing. The discourse has changed a lot, and so have the media and the political map. Haokets needed to lead a new path, or at least be the platform on which that path takes shape, but that didn’t happen.”

Despite the sense among some of the veterans of the Mizrahi left that their movement has either stalled or failed, several organizations formed in the past decade are nonetheless giving new life to the Mizrahi struggle, even on relatively small budgets. In addition to the work of Amram on the Yemenite Children Affair, grassroots feminist groups like Shovrot Kirot (“Breaking Walls”), and Lo Nechmadim – Lo Nechmadot (“Not Nice” — a reference to Prime Minister Golda Meir’s description of the Black Panthers) are bringing the struggle back to the streets and putting the demand for housing and social equality at the forefront of their activism.

‘A community of outsiders’

While the debate about the future of the Mizrahi left will rage on, there is little disagreement over how significant the platform provided by Haokets has been for the political movement, the community that formed around it, and the staff themselves. “It’s my political home,” says Na’aman. “It shaped my political consciousness, first as a reader, and then I was blessed and privileged to take part in this beautiful project.”

Abdul Halim is equally wistful: “For me, it was one of the most important jobs that I’ve ever done, and that’s no exaggeration. I really felt that I was doing something that had an influence in the world, bringing stories that people wouldn’t hear or learn about otherwise,” she says.

Recalling her ethnographic research into the Haokets community, Benbenisti says that almost everyone she interviewed described themselves as an “outsider.” In an era when the sense of community seems further away than ever, she says, Haokets provided avenues for left-wing Mizrahim across the country, who otherwise would not have been in touch, to connect. “Haokets enabled us to meet, to attend events and protests together, and to disagree on the blog but still be discussing the issues together. Haokets created a community of outsiders.”

“Where would I be without Haokets?” Mehager asks himself. “I don’t even know. Haokets was the platform that allowed me to shape my own identity as an activist, and my whole career today is based on what began in Haokets. It’s my own history, it’s my own identity — I can’t imagine myself without Haokets.”

Noy believes the same. “It is that place that really gave each and every one of us a voice, and many people will forever be very grateful for that. When the history of the Mizrahi resistance in Israel is written, the role of Haokets will be clear.”