It was the winter of 1999, and Nasrin Elian had just finished law school. She was working at the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem in Jerusalem, when she received news that Israeli soldiers were expelling the Palestinian residents of Masafer Yatta, a cluster of villages in the South Hebron Hills region of the occupied West Bank.

“I went there immediately,” she recalls today, “and I saw jeeps loaded with equipment and soldiers throwing the residents’ belongings onto the ground in the fields.” Using the camera she brought with her, Nasrin documented the military’s expulsion of 700 farmers and shepherds that November day, leaving them homeless.

Following their petition to the Supreme Court, the families were allowed to return to their villages a few months later, pending a final decision on the status of the Palestinian residents of what Israel calls “Firing Zone 918” — a military training area declared in 1980 by Agriculture Minister Ariel Sharon as a means to take control of Palestinian land in the South Hebron Hills. In May 2022, the final decision came down: the Supreme Court rejected the families’ petition, and in so doing gave the green light to the army to carry out the expulsion for a second time. Now, in the face of the renewed threat of forcible displacement, B’Tselem has located the original photographs from 1999.

Wadha al-Jabareen, from the village Jinba, which can be found on maps dating back to the 19th century, is now an 80-year-old great-grandmother. In the photos, taken as she spoke with a journalist just hours after the expulsion, her eyes are red and puffy from crying. Her grandson, Qusay, then 4 years old, today has two children of his own.

“They arrived at sunset, and parked their truck at the entrance to the cave where we lived,” Wadha recalls of the events as she looks at the old photographs from that day. “Back then there were 14 families living in the village. Soldiers put all of our possessions into the truck — clothes, pots and pans, food. One of the soldiers raised an iron bed while my grandson, Zakaria, was on it. A baby. I grabbed the bed from the soldier’s hand and said to him ‘What are you doing?’. He said he was doing it ‘So that you will leave.’ When one of the officers saw there was a baby, he told the soldier to put down the bed.”

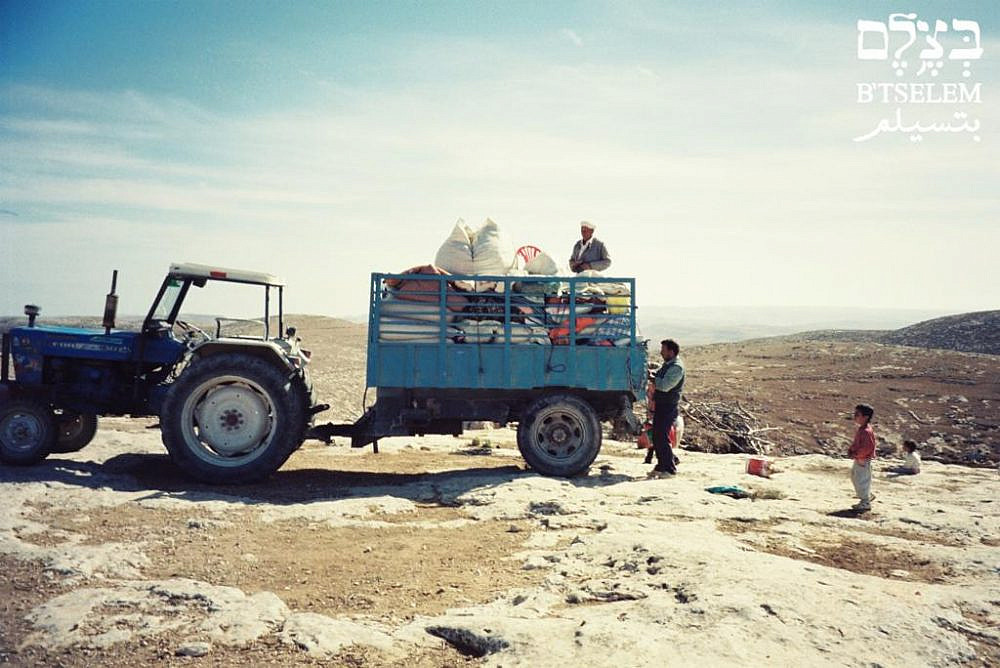

In the photos, the soldiers are seen unloading the families’ belongings in the desolate area to which they were expelled, along the road that leads to the Israeli settlement of Carmel. The soldiers created a human chain, passing along the families’ belongings from one person to the next in order to empty the trucks. On the trucks you can also see carpets, pita bread, pots, gas lamps, and coats.

“Around 100 soldiers took part in the expulsion,” Wadha continues. “Some women ran away from the village, but I and a few old women refused to leave our land. The soldiers didn’t leave us anything. No mattresses, no blankets. They took the flour, the bread, the food, to force us to leave.”

Many children can also be seen in the photos. Some of them are looking at the camera in wonder, some are crying, and some are rummaging through the piles on the ground. One photo shows a teddy bear tossed between rocks. If there were to be another expulsion now, the number of children forced to leave their homes would be double what it was in 1999. The army began preparing for the new expulsion in January of this year, before even receiving the government’s approval.

Nidal Abu Younis, today the head of the Masafer Yatta Village Council, is, in the photographs, a 23-year-old man, still single. He is standing with a group of men piling up lamps, birdcages, and mattresses onto tractors. Abu Younis explains that they sorted the piles so that they could bring them to storage in a nearby town. That night, the families had to figure out where to sleep: some of them crowded into neighbors’ homes, others slept under the open sky. Soldiers patrolled the displaced villages to make sure that no families had returned to their homes.

“These photos helped to capture the world’s attention,” Abu Younis recalls. “The next day, the media arrived, as did human rights groups and Arab members of Knesset. Their interest in us, their solidarity, contributed to the temporary order issued by the Supreme Court that allowed us to return to our homes until their decision last year, the worst we could have expected.”

Mahmoud Hamamdeh, a resident of the village Mufagara, who appears in the old photographs, was expelled with his family. He became the face of the struggle in 1999: he was interviewed in Hebrew-language media, he invited people to tour the area, and he received a permit to attend a solidarity conference with the displaced families at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque, where he appeared alongside the author David Grossman and other left-wing Israelis like Shulamit Aloni and Mossi Raz.

“I didn’t know where we’d go after the expulsion, I looked for a place to live,” Hamamdeh says. “I asked people in the village next door, Tuwani, if I could live with them. They agreed, cleaned an empty cave, and prepared it for me and my family.” He explains that the soldiers forced them to clear their houses themselves, and whoever refused to leave would be arrested. “That’s why they arrested my brother,” he adds.

Most read on +972

Hamamdeh still lives in Mufagara, the village where he was born. “In the two decades since these pictures were taken, they’ve destroyed my house twice,” he says. “The neighbors’ house they destroyed more than twice. I saw how soldiers wrecked the village mosque and the electrical infrastructure, and I saw how the settlers established two outposts next to my village — Avigail and Havat Ma’on — which received all the infrastructure they needed.

“Nothing has changed, except that now, in my old age, I have white hair. The threat of expulsion, the return of these events, it’s all just a matter of time.”

This article first appeared in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.